Maritime life has traditionally been considered a masculine world, with the role of women often overlooked. In recent years there has been a wave of new research dedicated to re-examining and capturing the contributions of the female maritime workforce and the varied roles they have played over the centuries.

From Britain’s first female sea captain to a woman fighting for equal pay in the male-dominated welding industry – explore the remarkable stories of three Scottish women who found their way in the shipping industry.

Betsy Miller – A life by the sea

Elizabeth ‘Betsy’ Miller was born in 1792 in Saltcoats, Ayrshire. Her father, William Miller, was a Merchant Taylor at the time of her birth and would later go on to become a timber merchant and sea captain.

A watercolour painting of Saltcoats Harbour by the artist R. S. Workman, dated 1891. Saltcoats Harbour was the subject of many Victorian and 20th century artists having much quaint charm. ©North Ayrshire Council Museums Service. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

His ship, the brig Clytus, transported cargo around the west coast of Scotland and across the sea to Ireland. Betsy was captivated by the sea, and often accompanied her father on his journeys. She worked in the family business as an office assistant and acted as ‘ships husband’ (an agent who has responsibility for managing a ship when it is in port) to her father.

Tragedy struck when Betsy’s brother, who had been primed to take over the family business, drowned. Her father’s health was declining, and the family were in debt. Betsy decided to step up and take charge of both the ship, its 14-man crew, and the family business. She would go on to captain the Clytus for over two decades.

Britain’s first female sea captain

Betsy became a skilled and well-respected captain amongst her contemporaries. A Glasgow Herald Report from 1852 stated that she had:

“weathered the storms of the deep when many commanders of the other sex have been driven to pieces on the rocks. Her position and attitudes on quarter-deck in a gale of wind are often spoken of, and would do credit to an admiral.

We must not omit to state, that during the long period of this singular young lady’s diversified voyagings, no seaman of her crew, or officer under her command, could speak otherwise of her than with greatest respect.”

Betsy retired due to ill health in 1862, aged 70. She left the Clytus and the running of the family business to the care of her sister, Hannah. By this point, she had paid off the family debt and established a comfortable life for herself and her remaining family.

She became the first woman to be granted a sea captains license from the Board of Trade and is widely regarded as the UK’s first female ship captain.

Against the Tide: Victoria Drummond

Thirty years after Betsy’s death, Victoria Drummond was born. Victoria’s early life was very different to that of Betsy. Her family were part of the aristocracy and owned Megginch Castle in Perthshire. She was named Victoria after Queen Victoria, who was one of her Godmothers, and was later presented as a debutant at the court of George V.

Megginch Castle has been owned by the Drummonds since the seventeenth century. © Perth & Kinross Council. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Victoria was interested in mechanics from an early age and inspired by visits to a local engineering company, decided that she wanted to become a marine engineer. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, many roles that had been traditionally held by men became available to women. In 1916, Victoria was hired as an apprentice mechanic by the Northern Garage in Perth. She also studied maths and engineering at Dundee Technical College (now Abertay University) three nights a week.

This photograph, taken by Professor Steggall from the roof of the Technical Institute, shows the east of Dundee city c.1890. © University of Dundee – Archive Services. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Salacious scandal or deceitful discrimination?

Victoria stayed with the garage until 1918, when she moved to the Caledon Shipbuilding Company in Dundee. She remained at Caledon for four years, completing her apprenticeship whilst employed there. She started in the pattern shop, then moved on to the finishing shop and finally the drawing office.

In 1922 Victoria was ready to go to sea. She took on the role of 10th engineer on board the SS Anchises, a cargo ship that sailed between the UK, Australia and China. She would make four journeys on the Anchises between 1922 and 1924. During this time, she experienced discrimination from some of her colleagues, and was accused of having an affair with one of her crewmates, which she denied.

SS Anchises was built in 1947 by Caledon Shipbuilding & Engineering Company of Dundee. © Scottish Maritime Museum. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

This would not deter her – she was ambitious, and her ultimate goal was to become a ships chief engineer. After leaving the Anchises she would spend the next two studying for her second’s exam, which would qualify her to sail as a ships second engineer, reporting directly to the chief engineer. Victoria had hoped that once she passed this exam, she would be able to return to the Anchises. But they would not re-employ her. She believed that “they feared a scandal”, referring to the suggested affair between herself and her crewmate. Victoria found employment on board the TSS Mulbera soon after, sailing as fifth engineer. She remained with the Mulbera until 1928, travelling to several countries in east Africa, India, and modern-day Sri Lanka.

The Female Fight For Marine Engineering

After leaving the Mulbera Victoria spent the next 12 years ashore. She began to study for the Chief Engineers exam, which she would sit 37 times over a number of years and never pass. One of the examiners would eventually confide to Victoria’s tutor that she was being failed because she was a woman. She would later go on to pass the equivalent qualification from the Central American country of Panama.

Victoria decided to return to the sea in March 1940, six months after the beginning of the Second World War. In the same year, Drummond’s ship, the SS Bonita, was attacked by the Luftwaffe whilst in the Atlantic Ocean. Victoria’s skill and experience in the engine room allowed her to increase the Bonita’s speed to a rate never achieved previously, meaning the ship captain was able to manoeuvre the vessel as needed to avoid enemy bombs. She was praised for her actions, and later awarded an MBE and a Lloyds War Medal for her bravery.

Victoria went on to spend the rest of the war and much of the period after at sea, achieving her goal of being employed as a ships chief engineer. She undertook 49 voyages in total before retiring in 1962. Today she is celebrated as the UK’s first female marine engineer.

Welding Her Own Path: Bella Keyzer

Reproduced courtesy of Su Nicoll

Our final woman is Isabella ‘Bella’ Keyzer, nee Mitchell. Bella was born in Dundee in 1922, the youngest of three children. After leaving school at age 14, Bella went to work as a weaver in a local jute factory. Jute was the largest industry in Dundee at the time, and most of the workforce were female. Wages were poor, and it was very much considered ‘women’s work’. In an interview later in life, Bella would describe the industry as a “soul destroying place” and “uninteresting”.

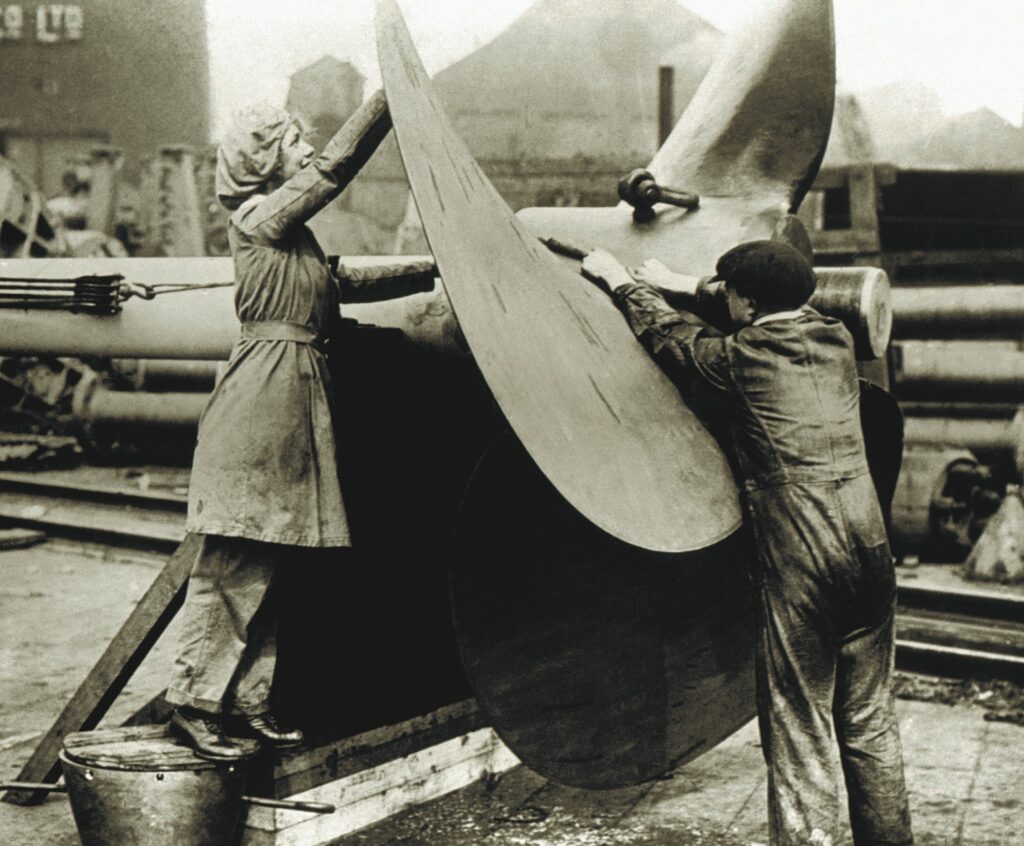

The outbreak of the Second World War led to a labour shortage in jobs traditionally held by men. This resulted in a demand for more women to enter the workforce as a means of filling employment gaps. Bella initially worked in a munition’s factory, but in 1942 she was trained as a welder and was employed by the Caledon Shipyard, where Victoria Drummond had also previously worked.

The Caledon Shipbuilding and Engineering Co. Ltd., Caledon West Wharf, Dundee. Zoom in on Canmore

Many of the male workforce were not happy with this arrangement. Bella later joked that women were allowed into the shipyard provided that they “all went out again at the end of the war”. This didn’t deter Bella, who discovered a passion for welding. But it wasn’t always plain sailing. The female employee’s wages were significantly less than those of their male counterparts. This would eventually lead to Bella asking for a pay rise.

Shattering the Second World War glass ceiling

Bella’s father was a trade unionist, and politics was very much part of the family. Bella and her female colleagues had only been provided with temporary union cards and weren’t actually allowed to attend meetings. However, the boiler makers union backed Bella. It was decided that before a pay rise could be awarded, Bella would have to pass a welding test. Following her success, wages increased from £2 12s 6d a week (around £103.28 in 2017) to £3 14s 8d a week (around £146.89 in 2017). It was still much less than what the male welders earned.

In addition to being a woman in a ‘man’s’ workplace, Bella also faced another challenge. She was an unmarried mother. In 1941, she had met Dirk Keyzer, a chief engineer in the Dutch Royal Navy. She became pregnant the same year, but due to the war and his line of work, Dirk was frequently overseas. Despite the social stigma of the time and hostility she experienced from some of her colleagues, she never tried to hide her son’s existence and was a proud mother. She would go on to marry Dirk in 1949.

Bella and the other female welders at Caledon Shipyard were made redundant before the end of the war for reasons that were not explained. She moved to the Netherlands with her family in 1949, returning to Scotland in 1957. In 1976, she attended Dundee Technical College to retrain in welding. She finally managed to get a job back with Caledon Shipyard, but only after applying as Mr I. Keyzer. She was thrilled to return to her old place of work, later saying that it was “the climax to the game I had played…in these thirty years…”.

In 1992 Bella received an award from Dundee Council for promoting women’s equality.

Want to explore more Women’s History?

From the mysterious Viking woman at Broch of Gurness to the marvellous Mary Burton – explore many more stories of Scottish Women’s History on our blog.

Sign up to our blog newsletter to get the latest stories straight delivered to your inbox.