Want to impress with your historical knowledge as well as your super-insightful punditry during Euro 2024? Here’s three historic tales connecting Scotland with each of our group stage opponents…

Germany: The Rocket Man

Germany v Scotland (Friday 14 June, Munich)

Franz Beckenbauer and Billy Bremner shake hands before a Scotland v West Germany friendly in November 1973. (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd, licensed via Scran)

Scotland has many connections with Germany. When Queen Victoria and Prince Albert purchased Balmoral Castle in 1852, one of the deciding factors was that the landscape reminded Albert of his homeland of Thuringia.

The Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site covers the Antonine Wall here in Scotland, along with Hadrian’s Wall and the Roman borders known as Limes in Germany. Our experts at HES work closely with their German counterparts to protect and understand this shared archaeology.

Another lesser-known – but rather explosive – link is the story of Gerhard Zucker, an entrepreneur and engineer from the small German town of Hasselfelde. In the early 1930s, Zucker dedicated himself to perfecting a revolutionary new system of communication: delivering mail by rocket!

In the last days of July 1934, a curious episode of engineering failure played out in the skies over Scarp, west of Harris (© Crown Copyright: HES, licensed via Scran)

Rocket post

Zucker travelled around Germany demonstrating his “rocket post” but found his countrymen were far from impressed. So, in 1934, he headed to Britain.

Zucker’s rocket full of mail failed to complete the trip between Hushinish and Scarp (© Crown Copyright: HES, licensed via Scran)

Switzerland: Tragedy on the Matterhorn

Scotland v Switzerland (Wednesday 19 June, Cologne)

Derek Johnstone in action during Scotland v Switzerland in 1976 (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd, licensed via Scran)

To use a classic football cliché, Scotland could find themselves with a mountain to climb if they concede early goals to a well-organised Switzerland side. It’s an appropriate turn of phrase for our Swiss story…

Cummertrees is a small village just outside Annan. It’s home to Kinmount House, once a seat of the Marquesses of Queensberry. The house is Category A listed and its grounds are listed in our Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes. Nearby you’ll find the marquesses’ traditional burial place, the Douglas Mausoleum. There, a plaque alludes to tragic events which took place in Switzerland on 14 July 1865.

Kinmount House (© Colin McWilliam, licensed via Scran)

Lord Francis Douglas, the son of the 8th Marquess of Queensberry was born in Cummertrees on 8 February 1847, By the time he was 18, he was a keen mountaineer. In the summer of 1865, he linked up with the English climber, explorer and illustrator, Edward Whymper.

Whymper was obsessed with reaching the summit of the mighty Matterhorn, and had long been engaged in a race with the Italian Jean-Antoine Carrel to be the first to do so.

In the early hours of July 13, a group consisting of Whymper, Lord Douglas, Charles Hudson and Douglas Hadow began another attempt. Their guides were Frenchman Michel Croz and a father-son duo of Swiss guides, both named Peter Taugwalder.

By lunchtime the following day, they had reached the summit. Whymper recalled how:

The slope eased off, and Croz and I, dashing away, ran a neck-and-neck race, which ended in a dead heat. At 1.40 p.m. the world was at our feet, and the Matterhorn was conquered. Hurrah! Not a footstep could be seen.”

Tragedy strikes

After an hour on the summit, the group began a careful, laborious descent, connected by rope. Disaster struck when Hadow slipped and fell onto Croz. Unable to cling onto the rockface, the two men fell, pulling Hudson and Douglas down with them. Tragically, the rope snapped. Whymper later wrote:

I heard one startled exclamation from Croz, then saw him and Mr. Hadow flying downwards ; in another moment Hudson was dragged from his steps and Lord F. Douglas immediately after him. All this was the work of a moment

For two or three seconds we saw our unfortunate companions sliding downwards on their backs, and spreading out their hands endeavouring to save themselves; they then disappeared one by one and fell from precipice to precipice on to the Matterhorn glacier below, a distance of nearly 4,000 feet [1,200 m] in height. From the moment the rope broke it was impossible to help them.”

Controversy and debate followed the accident, with some blaming Whymper. It was even suggested that the survivors had cut the rope, which is on display at the Matterhorn Museum, to save themselves from falling.

The bodies of Croz, Hadow and Hudson were located in the days following the incident, but Douglas has never been found. The young adventurer born in Dumfries and Galloway is one of over 500 climbers to have lost their lives on the Matterhorn.

Hungary: The Musician and the Saint

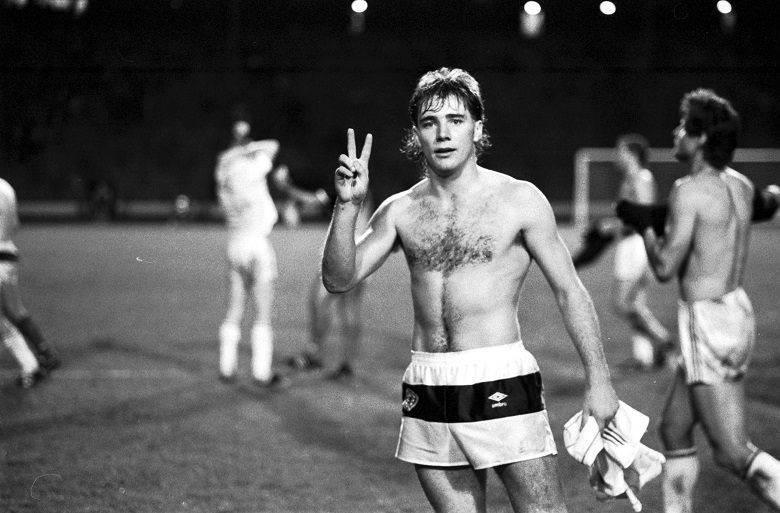

Ally McCoist holds up two fingers after scoring twice for Scotland in a 2-0 win against Hungary in 1987 (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd, licensed via Scran)

Scotland vs Hungary (Saturday 23 June, Stuttgart)

In Edinburgh’s Morningside Cemetery you can find a gravestone adorned with a carving of seven stringed lyre. An inscription in Hungarian reveals it to be the resting place of George Lichtenstein (1827-93).

Born in the town of Szigetvár, Lichtenstein forged a political career as well as a musical one. He worked for the activist Lajos Kossuth during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. This put him in danger during the war with Austria which followed. He fled Hungary and, from 1856, settled in Edinburgh.

As a music teacher, Lichtenstein had an enormous influence on the capital. He was founder and president of the Edinburgh Society of Musicians and was given the seal of approval to tutor young royals staying at Holyroodhouse.

The grave of George Lichtenstein (Stephencdickson, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

The arrival of a saint

One of the most revered figures in Scottish history, Saint Margaret, was also born in Hungary, in around 1045. Her father was Edward the Exile, a prince who was banished from England by King Cnut.

In 1057, Edward was named as an heir to the English throne. He left Hungary with his wife Agatha, son Edgar and daughters Margaret and Christina. He died very shortly after arriving in England, leaving his family to reside in the royal court.

The Norman Conquest of 1066 forced them to flee to Northumbria. From there, Agatha planned to return with her children to the Hungary. Legend has it that a storm forced their ship to re-route to the Kingdom of Scotland. The spot in Fife where it landed is today known as St Margaret’s Hope.

Will there still be all to play for in Scotland’s last group game? We (St Margaret’s) Hope so!

Enjoy the games!

Now it’s over to Steve Clarke’s team to hopefully make some more history. Who knows, maybe we’ll find ourselves using this blog format again in the knock-out stages…

In the meantime, we’ve enough archive photos relating to The Beautiful Game to fill Hampden Park (figuratively speaking). After that, you can read up on the world’s oldest football. It was discovered in the rafters of the Queen’s Chamber at Stirling Castle.

For more sport on the blog, check out Scotland’s most unique sporting venues or the history of cycling in Scotland.