Our cover image shows members of RAF 516 Squadron at Dundonald Airfield (© Dundonald Aviation Centre)

The largest seaborne invasion in history began on the morning of 6 June 1944, when Allied forces landed on the French coast as part of Operation Overlord. It was the beginning of an enormous human effort of an estimated 397,000 sailors, soldiers and airmen which paved the way to the liberation of France.

But the story of the Normandy Landings does not begin on “D-Day”. Preparation for the invasion began in 1943, with factories increasing production and various deception campaigns drawing attention away from the real plans. While you might first think of troops and tanks amassing along England’s south coast, the whole of Britain played its part. Read on to discover the traces of D-Day that can be found here in Scotland.

Training for D-Day took place on beaches across Scotland. Landing craft rehearsals were controlled by loudspeakers from this tower in Cromarty. (© Cromarty Courthouse Museum, licensed via Scran)

Recreating the Atlantic Wall

One of the major obstacles which stood between the Allies and Nazi-occupied Europe was the system of fortifications and defences known as the Atlantic Wall. It was constructed between by 1942 and 1944 by more than half a million drafted French workers.

The wall would often appear in Nazi propaganda, which talked of its great strength and length, supposedly stretching from France’s border with Spain to the top of Norway. You can still find parts of the Atlantic Wall across mainland Europe – but did you know there’s a piece in Scotland? Well, sort of!

The “Atlantic Wall” at Sheriff Muir (© Crown Copyright HES, licensed via Canmore)

Practicing breaching the Atlantic Wall was key to a successful invasion, so replicas of the German defences were built in Britain from 1943. One such mock-up can be found at Sheriff Muir, a windswept hillside near Stirling. This “Atlantic Wall” is 86 metres long and 3 metres high, and is covered in the scars of being hit by countless bullets and shells.

The Sheriff Muir site, which has a long history of being used for military training, also features anti-tank ditches, bunkers, trench systems and concrete platforms intended to represent landing craft. One officer who took part on the exercises at Sheriff Muir recalled:

We began some Combined Operations exercises, pretty primitive at first, known as ‘dryshod-exercises’. A road or some other suitable landmark represented the coastline, and if you were on one side of it you were technically afloat and on the other side on land again. Men and vehicles were fed across the ‘coastline’ at specified intervals to represent landing craft discharging their contents.”

There’s no such activity there today, but the unique training ground is protected as a scheduled monument, recognising the vital role it played in helping Allied troops prepare for D-Day.

Making the Mulberry Harbours

The 156,000 soldiers that stormed the beaches on 6 June were just the beginning of a monumental amount of troops and resources which needed to flow into France. It was estimated that 18 tonnes of supplies needed to come ashore every day following the landings.

A Mulberry Harbour in use at Arromanches (© HES, licensed via Scran | part of NCAP)

To achieve this without having to capture heavily defended harbours, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the development of floating piers capable of rising and falling with the tides. The result, after various prototypes and trials, was “Mulberry A” and “Mulberry B”.

They were towed across the English Channel in hundreds of individual parts, and constructed in the days following the invasion. “Mulberry A” suffered from storm damage on 19 June, but, over ten months, 4 million tonnes of supplies, 500,000 vehicles and 2.5 million men passed through “Mulberry B”.

Sea Trials

The coastal resort of Garlieston was used as a practice ground for the Mulberry Harbours used on D-Day. (© St Andrews University Library, licensed via Scran)

More than 500 British firms started developing and constructing the Mulberry harbours in 1842. They included Lobnitz and Company in Renfrew and Alexander Findlay and Company of Motherwell.

Meanwhile, the waters around Garlieston, in Dumfries and Galloway, proved perfect for carrying out rigorous sea trials in 1943. The beaches and tides were similar to those which would be encountered in Normandy, plus the remoteness of the area helped maintain secrecy.

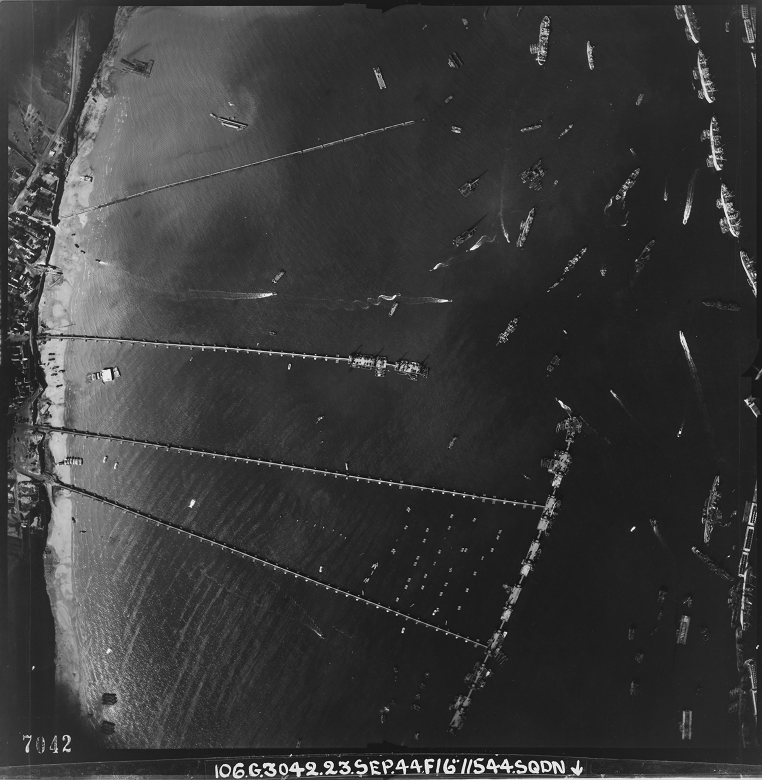

This aerial photo taken in 1946 shows the Mulberry Harbour pontoons in Rigg Bay (© HES, licensed via Scran | part of NCAP)

Remnants of the trials can still be seen today. Most striking are seven concrete pontoons which lie beached on the rocks. Originally codenamed ‘Beetles’, they would have supported a floating roadway.

At nearby Rigg Bay, a stone plinth hints at one of the other prototypes. In this rejected harbour design, the plinth was used as a tethering point to secure a roadway.

One of the “Beetles” (© Crown Copyright HES, licensed via Canmore)

Like Sheriff Muir’s “Atlantic Wall”, the remains at Garlieston are very important to our understanding of D-Day. They too are protected as a scheduled monument.

Assistance from the Air

The B-listed St Rollox Locomotive Works in Springburn, Glasgow helped produce Airspeed Horsa gliders for the Normandy Landings

Operation Overlord wasn’t all about landing by sea. Aerial manoeuvres before, during and after the landings were crucial. 18,000 paratroopers jumped into the invasion area in the early hours of 6 June. Others landed by glider to capture key bridges over rivers and canals. More than 14,000 sorties were flown by Allied Air Forces in support of the landings.

Air Force support was also essential during D-Day training. In Scotland, much of this support was provided by the RAF’s 516 Squadron.

Members of 516 Squadron at Dundonald airfield in 1944 (© Dundonald Aviation Centre, licensed via Scran)

Specially formed in April 1943, the squadron used a variety of aircraft to simulate air attacks during training exercises. This involved plenty of low-level flying around the Firth of Clyde and beyond, and live ammunition was sometimes used!

516 Squadron were based at RAF Dundonald. This basic airfield opened in 1940, but saw little use until D-Day preparations intensified. But the buzz of activity at Dundonald faded as quickly as it appeared. Their mission complete, 516 Squadron disbanded in December 1944, and the airfield closed six months later.

An aerial photo of Dundonald aerodrome taken in 1944. Initially it was a quiet airfield, however it became a hive of activity as D-Day approached (© Dundonald Aviation Centre, licensed via Scran)

Eye in the Sky

While 516 Squadron were firing their guns, an altogether different type of shooting was taking place above France. Aerial photography allowed the Allies to gather intelligence on the Normandy terrain and enemy defences.

Landing craft heading towards JUNO Beach on D-Day (Image courtesy of NCAP. Collection: ACIU, Sortie: US7/1730, Frame: 0098P (6 June 1944)

Pilots like Squadron Leader Peter Fahy flew reconnaissance missions solo, flying fast and at high altitude to avoid detection. The photos taken by his plane’s two vertically mounted cameras were rapidly developed and interpreted.

Squadron Leader Fahy, along with many other pilots, continued to fly ahead of the troops on the ground. They provided vital intelligence as the Allies advanced towards Paris, and eventually Berlin.

Landing craft and tanks make their way onto SWORD Beach (Image courtesy of NCAP. Collection: ACIU, Sortie: US7/1730, Frame: 2072 (6 June 1944)

A wealth of material associated with D-Day is held in the National Collection of Aerial Photography (NCAP).

Part of Historic Environment Scotland, the enormous archive offers a unique view of key moments in world history, including declassified Ministry of Defence reconnaissance imagery from WWII. Some 7,750 of NCAP’s remarkable images were captured on D-Day.

More wartime stories?

The images above are from Scran, our online learning service, and Canmore, home to the National Record of the Historic Environment. Each contains thousands of photos and videos from collections from across Scotland and beyond.

Elsewhere on the blog, you can read wartime stories from Stanley Mills, or discover the naval history of Scapa Flow. There’s also more from NCAP, including how evidence of the Holocaust was gathered from the air.