My ancestor, Geordie Lindsay, died in a cave in 1898, making me the descendant of one of Scotland’s last cave-dwellers.

But why did he live in a cave? This question would send me on a 7 year journey into the untold social history of Scotland, hearing voices from the past and instilling within me a responsibility to tell their story. It’s a story of exclusion, pride, and poverty, but a story I’d like to share with you this Gypsy, Roma and Traveller history month.

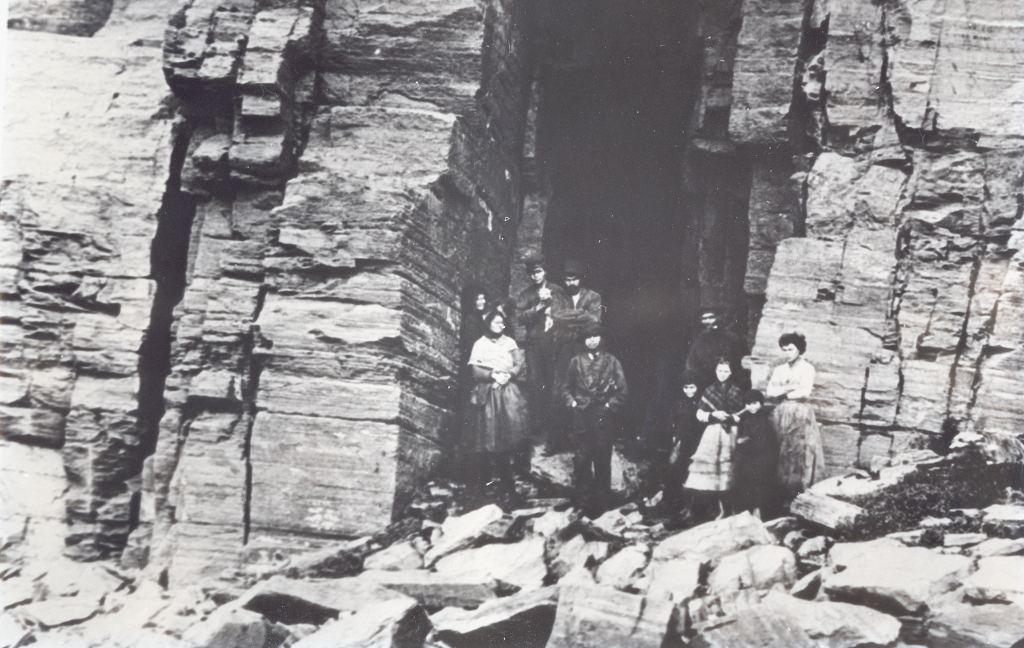

Our cover image of Wick Cave is from Caithness Horizons, Thurso.

The People

Geordie, my Great Grandad’s Grandad, “a quiet inoffensive man”, died aged 74 on 28 January 1898. He had lived in his cave at Covesea on and off throughout his life, then consistently for eleven years prior to his death. The newspaper article that announced his death was titled ‘Death of a well-known tinker’.

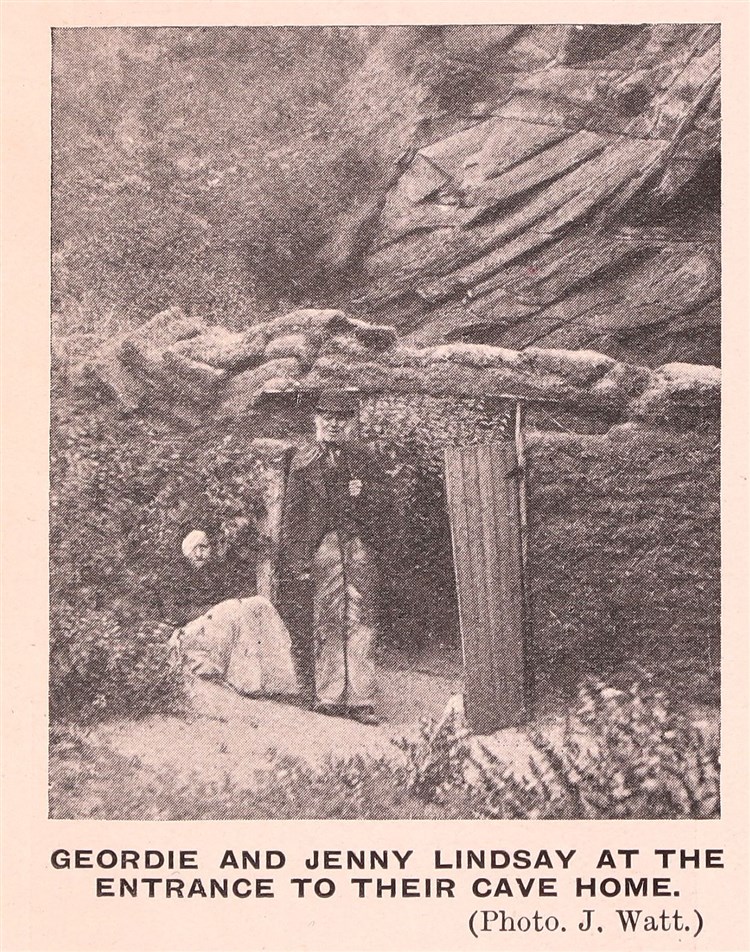

Not much else can be found on Geordie, there’s a picture of him and his wife Jessie outside his cave and another of his family inside the cave at a different time. Otherwise, there’s not much to go on. I know from census records that his extended family frequented caves as far north as Thurso and as far south as Arran. The records show that his family were occupied generally as ‘Tinsmiths’, ‘Basket-Makers’; ‘Horn workers’; and ‘Hawkers’. So, it’s probable that Geordie may have also plied one of these trades from his cave at Covesea. Travellers at the time would’ve provided crucial services to rural communities and offered repairing of items not easily replaced in those days, such as pots, pans, porcelain and cutlery.

Geordie and Jeannie pictured in The Northern Scot, 25 December 1908

I’ve found photos of his extended family at Dunnet and Wick, taken by interested collectors and journalists seeking to portray the so-called ‘primitive tinkers of the north’.

The photos show a proud people, healthy children, and give some indications of what daily life may have looked like. In one photograph we see equipment for pearl fishing, a woven basket, and cast-iron pots for cooking.

Historical accounts tell us that Robert Louis Stevenson met with Geordie’s extended family. They may have inspired characters in Treasure Island. Legends tell us of ghostly Traveller pipers in caves. In November 1883, the John O’ Groat Journal covered Travellers at Wick saving men from a sinking ship.

Poverty and prejudice

A staple-fixed plate, a craft of Scottish Travellers (image from Davie Donaldson)

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a very difficult time to be a Traveller in Scottish society, with poverty and social exclusion being at it’s extreme. This prejudice can most easily be seen in newspaper articles on Travellers from the time. This one, from the John O’ Groats Journal on 20 October 1911, explained why Traveller children should face segregated education:

Their [Travellers] dirty habits, however, often make people unwilling to grant them this privilege, even when it is felt to be a most un-Christian act to refuse them shelter on a stormy night. In this reality there is no available housing accomodation for them, and there is not the slightest doubt, but the people of the district would not be disposed to allow the tinker children to go to the public school and associate with the other children. The idea is repugnant to parents who have prejudice in favour of cleanliness, physically and morally.”

Clearly it wasn’t easy for Traveller communities to be accepted into society. Shamus McPhee, Gypsy/Traveller activist, explains in the 2017 book Gypsy Traveller History in Scotland that in 1908:

Living in tents and caves is banned and police are encouraged to monitor caves to ensure that they are not being re-occupied. Scottish Chief Constables recommend placement of all Gypsy children in Industrial Schools. In Perth and Kinross, nomadic children are ‘made to feel like lepers.”

The rationale for families like that of Geordie living in the caves, was explained in a quote from another Journal article called ‘Our Nomadic Population’. It stated:

They [Travellers] have fought out a long battle with society and they have retired from point to point till now they live between rock and ocean as a solemn protest against all who fight with them.”

Pushed to the margins

Lindsay’s Cave, Covesea, Elginshire (image from Davie Donaldson)

Stephanie Waterston, a researcher on the subject of cave-dwelling families, explains in a recent article about the lives of Caithness cave-dwellers that Travellers even changed their travelling patterns to use caves more regularly to navigate social policy:

You can see from the records they knew full well they couldn’t be classed as ‘vagrants’ anymore once a second generation was born here – so trying to drive them off via the Vagrancy Act was out the window for the authorities. Then they figured out that clever loophole in the Trespass Act about it not applying to ‘unenclosed places’ so the caves were fair game.”

The notion that targeted social policy had pushed Travellers to the margins of our coastline, was supported when I interviewed a Traveller elder who’s family had stayed in caves near Wick;

They a’ lived there cause they were left alane, the folk oh the toons would’nae gie them peace, an’ the authorities wid dae worse – they’d take the bairns. Better oot oh’ sight and oot oh’ mind.”

Pictish links?

The Craw Stane, a Pictish stone in Aberdeenshire

We can’t be sure when Travellers first began seeking refuge in caves, findings suggest that many caves frequented by Travellers had been inhabited since the Iron age. Interestingly, the cave where my ancestor died was just along the shore from Sculptor’s Cave – the site of a potential Pictish ritual site.

Many Scottish Traveller stopping places are located near sites of Pictish significance, such as standing stones and cairns. Nobody quite knows why, one theory was poised by Duncan Williamson, himself an accomplished Traveller tradition-bearer. He believed Travellers were descended from the Picts and recalled in his memoir The Horsieman: Memories of a Traveller 1928-58:

Father had said, “These stones [Standing Stones] belong to your people, your people a long time ago…”

Many of these cave sites also have early evidence of horn working and metalsmithing, so the jury is still out on who was staying in these places in our distant past.

Life in the caves

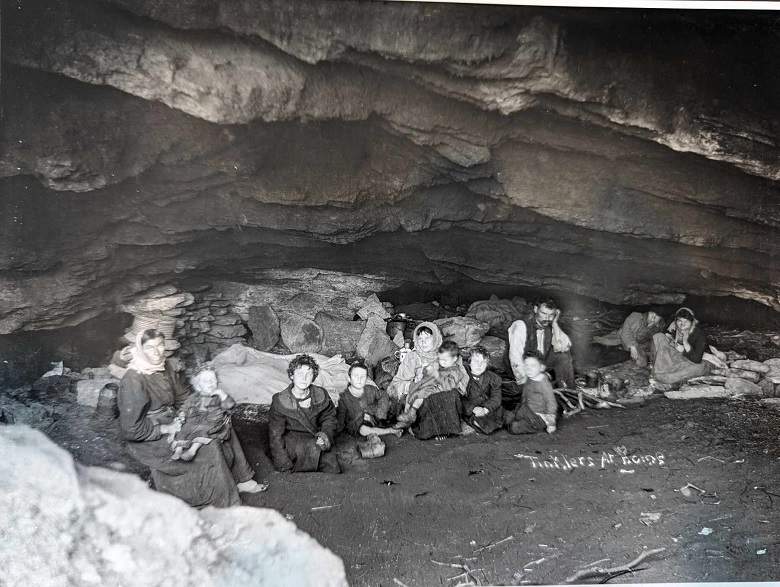

Travellers at Brough cave, Dunnet (image from the Wick Society Johnson Collection)

But it’s hard to imagine what it would’ve been like for people like Geordie living in these caves. An exercise made harder by the fact that our only descriptions come from a small number of accounts provided by authorities and writers of the day. These descriptions, written by the dominant society, are often filled with images of ‘savagery’ and seek more to other the inhabitants of the caves, than to understand them.

One example can be seen with Dr Mitchell, who wrote a Journal article published in July 1880 about a visit he made 11 years earlier, to Traveller families staying inside a cave at Wick:

We found twenty-four inmates – men, women and children – belonging to four families, the heads of which were all there. They had retired to rest for the night a short time before our arrival, but their fires were still smouldering. They received us civilly, perhaps more than mere civility, after a judicious distribution of pence and tobacco. To our great relief the dogs, which were numerous and vicious, seemed to understand that we were made welcome.

The beds on which we found these people lying consisted of straw, grass, and brackens, spread upon the rock or shingle, and each was supplied with one or two dirty, ragged blankets or pieces of matting.

Two of the beds were near the peat fires, which were still burning, but the others were further back into the cave, where they were better sheltered…

…besides the child spoken of, we were told of another birth in the cave, and we heard also of recent death there, that of a little child from typhus. The Procurator Fiscal saw this dead child lying naked on a large flat stone. Its Father lay beside it in the delirium of typhus when death paid this visit, to an abode with no door to knock at…

These dwellers in the cave are, of course, the dregs of the population; they are persons who have dropped out of the line of march. If they were transported to Edinburgh or Glasgow, they would naturally and necessarily find their homes in the slums of the city.”

Absent voices

A Traveller family who stayed in the caves at Caithness c.1910 (image from the Wick Society Johnston Collection)

Mitchell’s description to me reads very at odds with contemporary Scottish Traveller beliefs around cleanliness, gender division and modesty – all traditions I have no reason to believe would’ve been different in 1869. I believe the image he paints is one that takes advantage of the fact many would’ve never visited the families in the cave, but they would have no doubt been the article of great intrigue; and how they lived in the cave a great mystery to the so-called high society at the time.

The voices of families who made the cave their home are absent from all writings, and it is widely known that most would’ve been illiterate. Therefore, never knowing what had been written about them.

In an earlier description of the same cave (published in the Journal in May 1876), we do get a glimpse at the occupations of the families who made these places their home:

[they] were people popularly known as tinkers [sic], or workers in tin. The men cut, hammered, and shaped the tin, and the women did the soldering. They also made horn spoons, begged, told fortunes…left to themselves they would speedily die out.

…no sculptures in the caves – not even rude figures cut for amusement in an idle hour; and if the people ceased to inhabit them, they would leave nothing to show what their mode of life had been. Even the tin clippings which were in abundance in the loose stones would disappear with corrosion long before the lapse of a century.”

This account not only shows the adaptability of the people, but also the fragile state of their nomadic culture to the waves of time and increasing social pressure.

Conflict and colonies

By World War I, policy had made it increasingly inhospitable to inhabit the caves. Families were now prohibited from lighting fires in the caves making cooking and warming their homes impossible.

Then an inquiry by the Departmental Committee on Tinkers in Scotland was launched in 1917, igniting a debate on how to eradicate “tinkerdom” and several ‘solutions’ were suggested, including establishing labour colonies under the Small Holdings Colonies Act 1916. A colony of this type was proposed at a Crown estate site, Dorrery in Caithness for the Traveller families living at Wick cave, but fortunately this did not materialise.

After WWI, most Travellers would never return to the caves, many in my own family died fighting in the war and others feared returning to their way of life would mean losing their children.

Most took up poor quality accomodation in local areas, in the case of the families at Wick this meant moving into so-called ‘housing experiments’.

Recent findings

Examples of Horn cutlery and clothes pegs made by Scottish Travellers (image from Davie Donaldson)

No archaeological digs have been conducted on the cave where my ancestor died, but some recent developments further along the coast at Rosemarkie show interesting findings. Speaking with Steve Birch from the Rosemarkie cave project he said much of their dig has pointed toward Traveller use of the cave system:

We have recovered some great evidence for the use of the Rosemarkie Caves – particularly the Learnie Caves where we carried out more extensive excavations – including the organisational layout of the caves – hearths, division walls and bedding areas; food remains relating to diet and exploitation of resources, and of course the craft activities they were carrying out in the caves including tinsmithing, basketry and the manufacture of bone objects from horn cores – mainly sheep. It is obvious that the people were also collecting all manner of other materials including window glass, scrap metal (including from boats); while we also recovered quite a lot of leather shoes, some showing repair.”

Digs at Rosemarkie have also uncovered a range of ceramics, bottle glass, metal tools and many clay pipe fragments. Volunteer-led digs are shining a light on what life was like in these caves and protecting what fragments are left of the people who made them their home.

We may never know the full story of the individuals and families who lived in our caves, but we now know the reasons they lived there. We know that despite the hardships they faced, they were adaptable and skilled craftspeople.

I for one am proud to descend from Geordie. If my 7-year journey has taught me anything – it’s to look deeper into the heritage of our coastal landscape. There just might be a hidden voice from the past waiting to be heard.

More about Scotland’s Gypsy Heritage

If you enjoyed reading this blog, you might like to catch up with our other content exploring Scotland’s Gypsy Heritage:

- Rhona Ramsay and Maggie McPhee blog on the life of Jamie Macpherson in The loss of a son: Jamie Macpherson and his Gypsy heritage.

- Steven Robb from our Planning and Consents team discovers his family’s ties to the unique culture of the Kirk Yetholm Gypsies

A new exhibition – ‘Voices of our Coastline’ – will launch next spring, telling the stories of Geordie and many others who made the caves of Scotland their home.

About the author

Davie Donaldson is a social justice advocate with over a decade of experience, specializing in equity and anti-oppressive practice. Reputed for his work in advocating for Gypsy/Traveller communities, his interests lie in building ‘relational soil’, and platforming often unheard stories. He holds an MA in Anthropology and International relations from the University of Aberdeen, alongside being a regular content creator and host with BBC Sounds – most recently presenting the multi-award winning podcast – ‘The Cruelty: A Child Unclaimed’.

Davie Donaldson is a social justice advocate with over a decade of experience, specializing in equity and anti-oppressive practice. Reputed for his work in advocating for Gypsy/Traveller communities, his interests lie in building ‘relational soil’, and platforming often unheard stories. He holds an MA in Anthropology and International relations from the University of Aberdeen, alongside being a regular content creator and host with BBC Sounds – most recently presenting the multi-award winning podcast – ‘The Cruelty: A Child Unclaimed’.

www.conyach.scot | @DavieDonaldson