The 750th anniversary of Robert the Bruce’s birth falls in July this year. To mark the occasion, a new 3D model – produced from a cast of his skull – will be displayed to the public for the first time at Dunfermline Abbey.

The model is the result of a collaboration between historians from the University of Glasgow and craniofacial experts from Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) Face Lab. Thanks to advanced facial reconstruction techniques and CGI technology, it’s the most realistic so far in a series of attempts to capture the true likeness of the ‘Warrior King’. Read on to discover more about the many faces of Robert the Bruce…

The importance of appearance

An artist’s interpretation of Bruce dated 1797 (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk)

We often like to imagine how our heroes and idols from the past may have looked. As well as symbolising identity and age, the face is considered a way of seeing the character and personality of a person.

Certainly, Bruce’s character is often the subject of debate. He has been remembered as a courageous defender of the Scottish nation, but some saw him as a ruthless murderer who would stop at nothing to seize power.

Perhaps more importantly though, his physical appearance is crucial in settling the age-old debate over whether he suffered from leprosy – a contagious disease that disintegrates bone tissue. Seven centuries later, this question is still being debated by historians, artists, and forensic experts from around the world.

A depiction of Bruce on a coin (© Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk)

Bruce fought tirelessly to secure the throne, defeating his Scottish rivals, and ending the English regime in Scotland with his most dramatic victory at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. He then secured full Scottish independence in 1328 with the Treaty of Northampton.

Throughout his kingship from 1306 to 1329, Bruce led guerrilla warfare campaigns across Scotland, northern England and Ireland. This medieval combat would have been incredibly physically demanding and a debilitating disease such as leprosy seems at odds with the image of a strong and fierce warrior.

What did Robert the Bruce look like?

Bruce’s claim to the throne was also heavily contested throughout his reign and his facial appearance will have been key to his status and ability to inspire confidence as a strong leader, which is also be hard to reconcile with such a stigmatised disease.

A statue of Robert the Bruce at Edinburgh Castle

However, contemporary histories such as the Lanercost Chronicle (written by monks in northern England) and the Scalacronica, written by English knight Sir Thomas Grey, clearly refer to the king and his condition as ‘leprosus’ (leprosy). It is worth remembering that both these sources were written by patriotic Englishmen and calling someone a leper was around the most insulting thing you could say at the time, so they may have been seeking to discredit the King of Scots. Indeed, Sir Thomas was captured in an ambush and imprisoned by the Scots in Edinburgh Castle when he started writing Scalacronica in 1355.

For the most part however, historians regard the northern English chroniclers as fairly balanced, and they acknowledged Bruce’s right to the throne earlier than their southern English counterparts. Even in John Barbour’s epic poem The Brus, which positions King Robert as an illustrious hero, he describes an illness of some kind in Bruce in the last two years of his life but offers no description of how he looked. The general consensus is that the historical sources alone do not provide a clear answer.

The evidence

Dunfermline Abbey and Palace

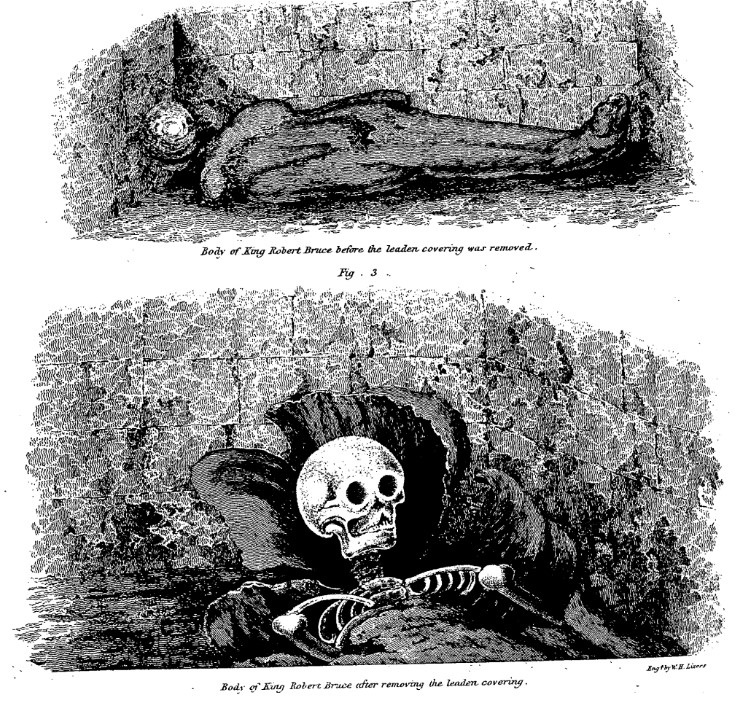

The truth about Bruce’s illness remained unresolved for centuries. Then, at Dunfermline Abbey on 17 February 1818, workmen clearing debris from the choir to make way for a new church stumbled upon a startling discovery.

They found two large slabs and beneath them a shallow grave containing a lead-shrouded skeleton. The tomb matched the descriptions of later medieval chronicles and was taken to be the burial site of Robert the Bruce.

An illustration of the tomb discovered at Dunfermline (Courtesy of ADS Archive)

The discovery caused huge excitement amongst local people in Dunfermline and across the country but also caused great concern for authorities in London that Bruce’s grave site could become a rallying point for nationalist dissent and calls for social reform.

The government never officially marked and secured the royal remains in the abbey and the only existing brass plaque was paid for by Bruce family descendants 70 years after the excavation. By then of course the new abbey church had long since been completed, enshrining the name KING ROBERT THE BRUCE in the stonework of its tower.

The large lettering reading KING ROBERT THE BRUCE can be seen on the tower.

Casts and Caskets

The first recorded assessment of the skull was carried out in 1819 by Professor Gregory (His Majesty’s First Physician for Scotland), Sir Henry Jardine (the King’s Remembrancer) and Mr Robert Liston (Surgeon). They described the skull as ‘in a most perfect state’ apart from missing some teeth, which they declared were caused by battle wounds and not by leprosy.

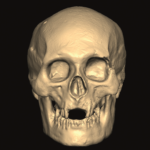

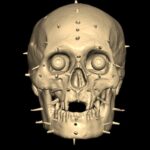

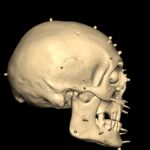

A plaster cast of the skull was made by an artist named William Scoular. Several copies of the cast exist today, including at Dunfermline Abbey and at the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow.

The cast made from Bruce’s skull

After the examinations the original skeleton and skull were sealed in pitch (tar) and reburied, though many relics and bones from the grave were reportedly stolen on that day. Since the remains are sealed, all further analysis has relied on casts of the skull which is assumed to belong to Robert Bruce.

The argument continued for another century, until in 1921 a casket thought to contain Bruce’s heart was unearthed at Melrose Abbey. His final wish was that his heart be removed, mummified, and taken on crusade, something he was unable to do himself in his lifetime.

Pilkington Jackson’s statue of Bruce at Bannockburn was commissioned in 1964. For the design, Jackson used measurements from Bruce’s skull, which was re-discovered at Dunfermline Abbey in 1818.

Warts and all

The discovery sparked a renewed interest in Bruce. In 1924, anatomist Karl Pearson examined the skull cast held at the University of Edinburgh’s Anatomy Department. Pearson agreed with the original assessments by Jardine and Liston from the grave site that Bruce did not have leprosy, and that the teeth were damaged by a battle axe or spear wound.

A year later, Professor Thomas Bryce assessed a cast held at the Hunterian. He pointed out that when the skeleton was first discovered at Dunfermline no one had remarked on diseased fingers or toes, which would clearly have been present with leprosy.

His conclusion that Bruce did not suffer from leprosy was largely uncontested until the skull cast was examined again in 1958. Advances in the study of human remains led D.R. Brothwell, an expert in osteoarchaeology, to argue that the missing teeth and sunken nose signified leprosy.

In 1965, two Danish authorities on leprosy in medieval skulls, Moller-Christensen and Inkster, agreed with Brothwell. They were able to back up their claims with examples of other skulls showing similar features.

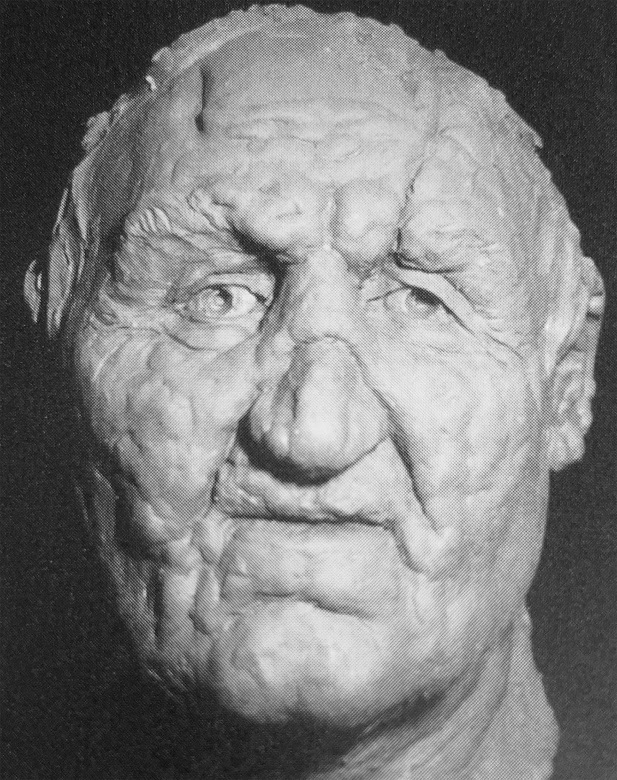

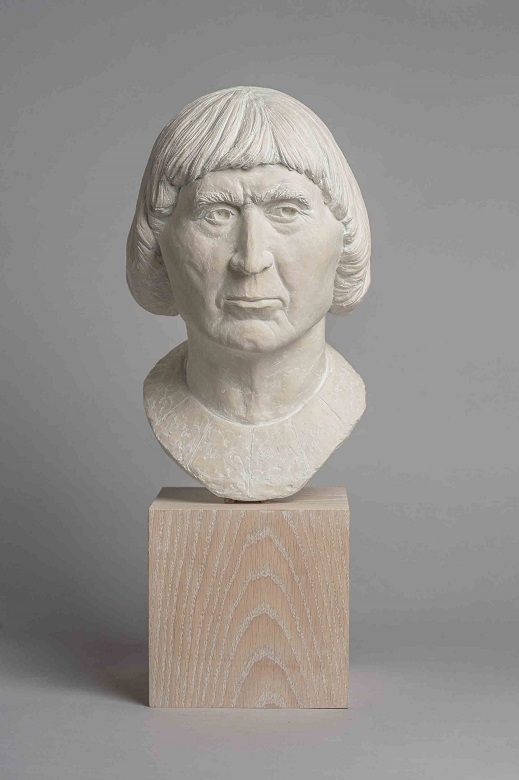

Richard Neave’s “warts and all” reconstruction (Copyright Richard Neave and University of Manchester)

In 1996 the heart thought to be Bruce’s was dug up for the second time at Melrose. It caused a huge media sensation against the backdrop of Scottish Devolution. Two years later the skull cast was re-examined by Dr Ian MacLeod, a consultant at the Edinburgh Dental Institute, assisted by Dr Richard Neave, one of Britain’s foremost forensic medical artists.

They produced a ‘warts and all’ reconstruction showing deep wounds to the head with a broken cheekbone and distended eye socket. The model also shows erosion around the front teeth, blunting of the bone margins around the nose and broken skin. These are all clear signs of leprosy.

A fresh face

In 2016 a striking revelation emerged from a collaboration between Professor Andrew Nelson, a palaeontologist from Western University in Canada and Canadian artist Christian Corbet. They were convinced that Bruce did not suffer from leprosy of any kind, based on analysis of a cast the Bruce family descendants had in their possession for almost 200 years – one the family believes is the original. In other words, not one of the several subsequent casts-of-a-cast, used in previous projects.

The 2016 Bruce reconstruction by artist Christian Corbet (Courtesy of Stirling Smith Museum)

The details of how Nelson and Corbet arrived at this conclusion have not yet been shared publicly. In 2017 Nelson submitted a paper titled ‘A palaeopathological assessment of the leprosy diagnosis for King Robert the Bruce’ to the International Journal of Paleopathology. However, the journal requested several revisions of the paper be made before they would agree to publish it and seven years later Nelson now has a ‘completely recast article in process’.

Corbet, whom the Bruce descendants have commissioned to produce family portraits in the past, depicts a much more expressive and flattering likeness. The clear skin and distinctive page boy haircut sit in stark contrast to Neave’s heavily disfigured model.

Picture perfect

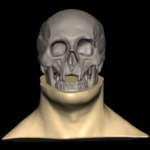

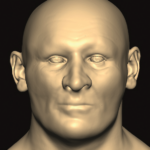

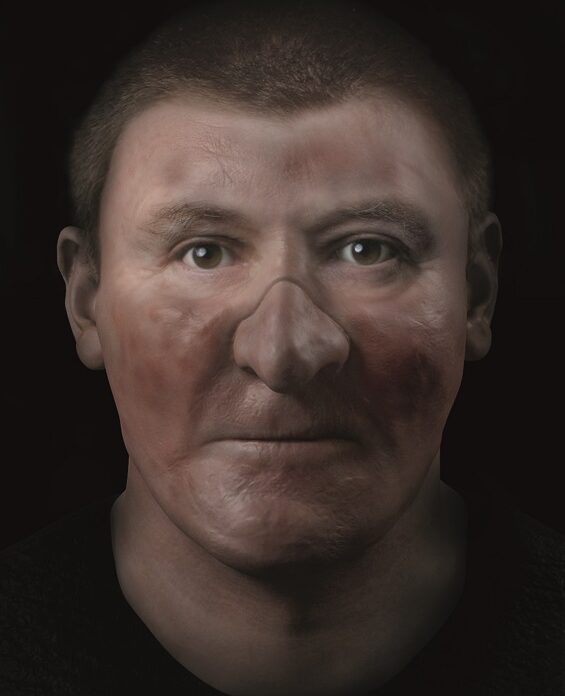

The model on display was first conceived of by Dr Martin MacGregor, a Scottish historian at the University of Glasgow. He was inspired by the discovery of the skeleton of King Richard III of England in Leicester in 2012 and reached out to craniofacial identification expert Professor Caroline Wilkinson, Director of Liverpool John Moores University Face Lab. The project received funding from the University of Glasgow’s Chancellor’s Fund in 2014, the year of the Scottish independence referendum.

Face Structure

The team were able to accurately establish the muscle formation from the positions of the skull bones on the cast held at the Hunterian Museum using a 3D laser scanner. The scanner reveals the shape and structure of the face, which shows a prominent chin and square jaw line.

Neck and Shoulders

From examining the muscle attachments to the occipital bone at the base of the skull it appears Bruce (if this is Bruce’s skull) had a large strong neck and shoulders. The nose is the least certain feature of this facial depiction due to the bone deterioration.

Skin layer

With CGI technology used in gaming and film, they added a realistically textured skin layer over the muscle structure to fill the face and generate a life-like appearance.

The depiction of the skin accounts for loss of elasticity with age including crow’s feet, eye bags, neck, and forehead creases. They also accounted for an average amount of fat over the surface of face for a white European male aged 50-59 in the 1300s, which is less than today’s average.

As for the hair and eye colours, these would normally be determined though DNA analysis, but this is not possible without actual bone, and the skeleton is sealed in tar. The project team relied on statistical evaluation of the probability of certain colours to determine that if it were Bruce he likely had brown hair and light brown eyes.

Regarding the headwear they referred to John Barbour’s epic poem The Brus, describing the first day of the Battle of Bannockburn when Bruce is charged by an English knight who recognises him by his crowned helmet known as a basinet. The head piece conveniently solves the possible hairstyle issue leaving focus on the face alone.

Face/off

Unlike earlier studies, the team concluded that the face did not show signs of healed battle wounds. However, regarding the leprosy question, they could not find a definitive answer without examining the rest of the skeleton.

Hedging their bets, they produced two versions of the digital reconstruction – one without leprosy and one with a mild representation of leprosy created using colour portraits of leprosy sufferers. They believe that if Bruce did have leprosy it probably was not strongly visible on his face, as this is not documented in the historical sources from the time.

Bruce depicted without leprosy

Bruce depicted with the effects of leprosy

For the final 3D physical model the team opted to portray only the version showing no visible signs of leprosy. The ‘life-sized’ model was produced using the 3D computerised facial reconstruction system and then printed using 3D printing technology in acrylic resin.

A beard wig was attached and then trimmed. Realistic plastic eyes were inserted with eyebrow hair and eyelashes. The headpiece includes chain mail and real leather strap. The project is well documented with several published research papers and is the most rigorous and realistic to date based on all available evidence and current technologies.

Case closed?

The complete Bruce reconstruction 3D model which is on display at Dunfermline Abbey

It is clear that interest in Bruce – and what his remains symbolise – has peaked and ebbed over the last 750 years. The different representations of him reflect advances in historical understanding, medicine, and art, as well as the social-political landscape in Scotland over time.

With the skull and skeleton sealed under tar below Dunfermline Abbey we may never know for certain if he had leprosy, but there are rumours of relics and bones from the gravesite that may still be in circulation and could hold the answers.

Bruce’s legacy in Scotland is still felt today and whatever illness he may or may not have had it certainly did not hold him back. We don’t know what the next 750 years will bring and while this is perhaps the truest representation so far it is unlikely to be the last face of Bruce we see.

The model will be on show to the public for the first time at Dunfermline Abbey from Monday 29 July until Saturday 7 December.

More Bruce?

You can join us in marking 750 years since the birth of Robert the Bruce by checking out trails, stories, activities and our brand-new retail collection on the dedicated pages of the HES website.

For more Bruce family history on the blog, read the impressive story of Christina Bruce and her defence of Kildrummy Castle.