Windswept and derelict, an elegant, gutted edifice once towered on the eastern outskirts of Dunbar. For a teenage Goth travelling the bus route from Eyemouth to Edinburgh, the ruin conjured fancies of Edwardian opulence with promenading parasols and ornate Art Nouveau decoration. It created a longing for a seaside spa getaway at the turn of the century.

Most of all, the weathered facade conveyed a strange sense of mourning. It hinted at a naïve but hopeful era, now long-lost to time. A century’s passing which left little more than an abandoned husk behind; too devastated to be rebuilt. This was the Hotel Belle-Vue.

The Belle-Vue in the 1970s or 1980s (© Genna Bard)

Finding the Flecks

I first discovered the hotel’s Edwardian origins – and how it sadly burnt down nearly a century later – during high school work experience at the John Sinclair House archives. It wasn’t until many years later that I began researching the history of the Belle-Vue in earnest. Initially, I was simply curious about its architectural history. But the unfortunate tale of the family who built and ran the hotel became increasingly compelling.

The grave of William Fleck (© Genna Bard)

Mrs Helen Fleck was a devout Catholic and the wife of North Berwick hotelier William Fleck. She lost her husband to heart disease in 1885. He was laid to rest alongside three infant sons in Dalry Cemetery, Edinburgh.

While raising her six other children, Mrs Fleck ran The Royal Hunting Lodge Hotel in North Berwick for nearly a decade. She built up an excellent reputation for catered galas and sports events.

In late 1892, she sold the hotel and moved to Edinburgh. There, she commissioned plans for a grand hotel up the hill from Dunbar train station, directly across from the parish church.

Grand designs in Dunbar

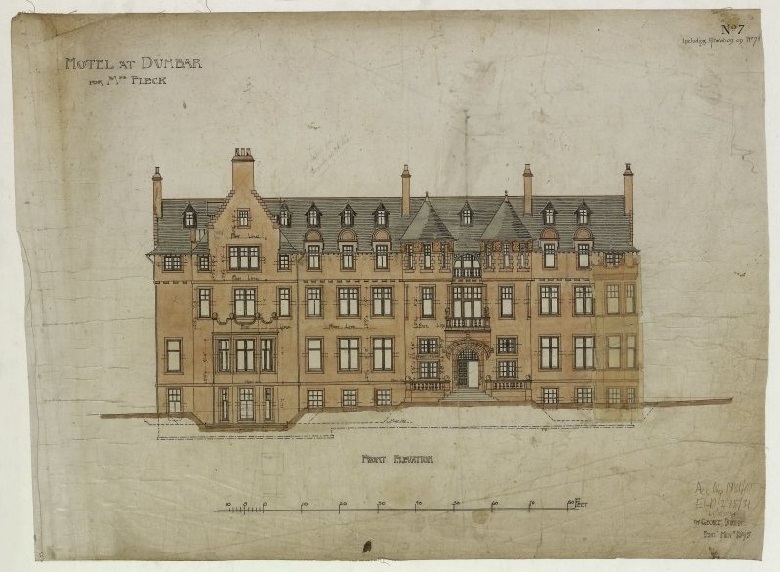

The front elevation of the Hotel Belle-Vue by architects Dunn and Findlay (© Courtesy of HES, Dunn and Findlay Collection).

James Bow Dunn and James Leslie Findlay drew up detailed plans in the Scottish Baronial style. They exhibited them at the Royal Scottish Academy in 1896.

They incorporated strong ornamental elements revived from post-reformation Scottish tower house architecture, making sure the Belle-Vue was both aesthetically pleasing and practical. Inspired heavily by the Arts and Crafts Movement, nature symbolism was built into every facet of the hotel.

The four seasons were represented over the four main guest floors. There were 12 public rooms for each month, 52 bedrooms for the weeks within a year, seven bathrooms for the days in a week and an impressive 365 windowpanes for days of the year!

Such symbolic emphasis in the structure always struck me as something more than mere design motif, hinting at an almost spiritual reverence for the natural order and the changing of the seasons. This early Art Nouveau styling was carried over to the internal design as well. There was plant motif decoration and a fully oak-panelled dining hall, which held up to 100 guests.

It appears the initial plans were adjusted slightly to mitigate the wild coastal weather. For instance, the heights of towers were reduced to avoid damage by high winds. Flat areas where rain might collect were removed. It’s clear that Helen Fleck wanted a building that would last to cement the family legacy.

Seaside luxury

Opening the summer of 1897, the Belle-Vue provided the luxury every discerning Edwardian traveller sought.

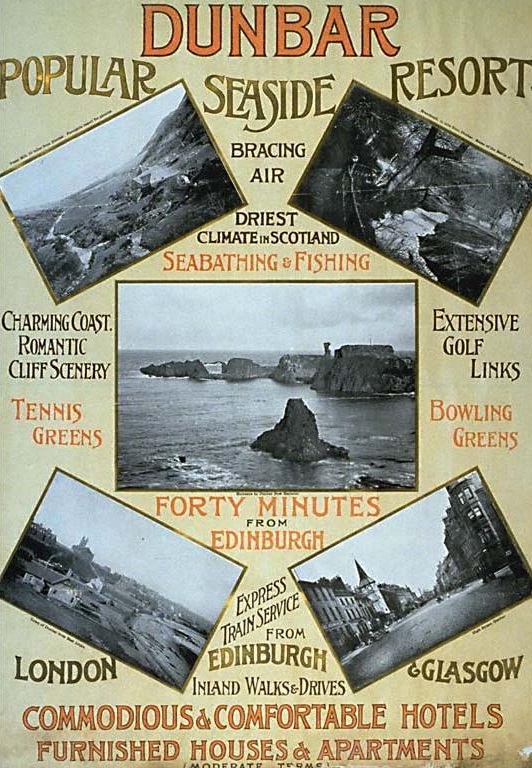

A travel poster from around 1900 encouraging visitors to Dunbar (© East Lothian Museums Service. Licensed via Scran)

Newspaper advertisements from London to Edinburgh extolled the virtues of Dunbar: scenic vistas, brisk sea breezes, fully-heated accommodation, and access to numerous leisure facilities. At the Belle-Vue, this would have included on-site tennis courts, an adjoining golf course, and use of the nearby seaside bathing pools. Eventually the front driveway would be widened with a garage added to the grounds for guests arriving by automobile.

Mrs Fleck ensured the Belle-Vue offered only the finest facilities for guests. The large capacity dining area made the hotel an excellent venue for socialite gatherings. It was well accustomed to hosting gatherings for local councillors and aristocracy from across Britain.

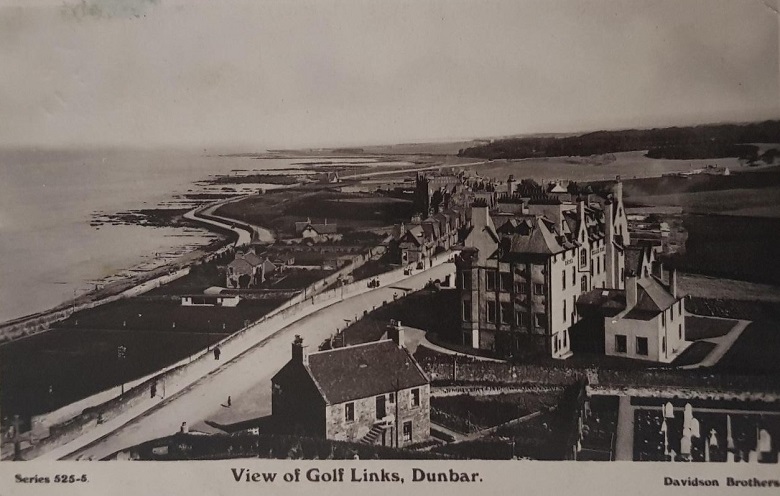

The outskirts of Dunbar and the Belle-Vue from c. 1900 (© Genna Bard)

In 1904, the Belle-Vue would host the flower-filled wedding reception of Helen’s daughter Christina in her marriage to Sergeant Hugh Murdoch, who she’d met as a nurse during the Boer War.

The Edwardian age of leisure had dawned; but alongside the new century’s optimism towards physical wellbeing came a poorly-understood and growing psychological crisis. Despite the initial success of the Belle-Vue, the first two decades of the 20th century would be cruel to the Fleck family.

Losing the Bell-Vue

In 1905, Helen’s second son, Andrew, took his own life in his Northumberland home, leaving his ill wife Lena to care for their infant daughter, Edith Annie.

The associated religious stigma of his suicide meant Lena received little support from extended relations and her own mental health deteriorated quickly. She was institutionalised at Castle Ward in Newcastle and died a couple of years later. Nine-year-old Edith Annie was sent to a Roman Catholic orphanage in Liverpool. She would go on to become a nurse in Oban, before settling in Edinburgh.

The First World War lead to many of Mrs Fleck’s daughters becoming nurses. Helen, Mary and Elizabeth following in the footsteps of their eldest sister, Christina. With so many soldiers returning from the war with severe disabilities and trauma, nurses were in great demand.

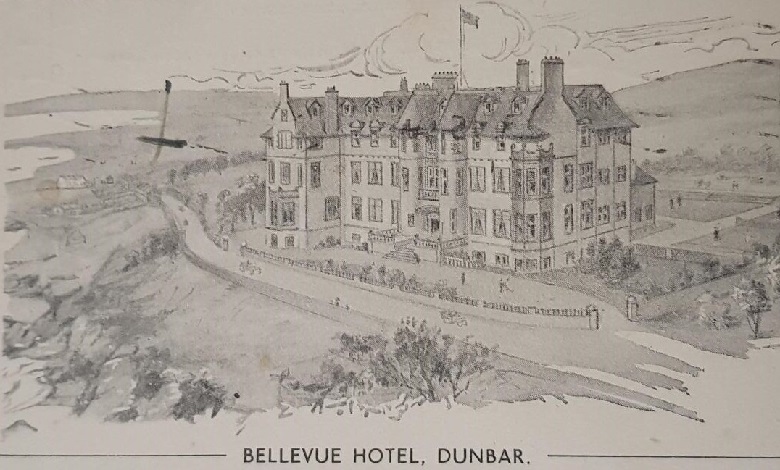

A drawing of the Belle-Vue on a postcard (© Genna Bard)

Sadly, Christina’s husband died on the front in Gallipoli and her teenage daughter emigrated to Canada after meeting a young soldier. Mary would lose her son during the Second World War, whilst both Helen and Elizabeth would choose to never marry.

Back home at the Belle-Vue, the remaining family members faced growing financial trouble. Helen and her eldest son Joseph were fined for storing petrol on-site without a distribution license, then forced to declare bankruptcy over new liquor licensing laws.

Helen Fleck lost ownership of the hotel in 1911, with Mrs Agnes Ruffell and her husband William becoming the new proprietors. Briefly displaced to the west of Scotland, the family were dragged through court again for breaking light restrictions during curfew at two separate hotels.

Joseph Fleck

Of all the unfortunate Fleck children, Joseph’s is the story that has stuck with me the most. Perhaps it’s the outsider nature of an eldest son who remained a bachelor when society would have expected him to marry and inherit. I feel it possible to ascribe aspects of queerness to his identity, though there is little hope of ever verifying this.

Joseph was certainly very successful in his own right. He presented the ‘Fleck Cup’ trophy to Dunbar Golf Club and bred award-winning St Bernards and Newfoundlands for regional dog shows. He regularly supported the local Yeomanry and Lifeboat societies and was re-elected multiple times as a town councilman.

The Shaftesbury Hotel in London’s West End, where Joseph Fleck worked as a manager (© Genna Bard)

Ever the socialite, Joseph Fleck overcame the loss of the Belle-Vue by throwing himself into managerial roles at the Station Hotel in Oban and the Imperial Unionist Club in Glasgow. As the war worsened, he took a position managing the Shaftesbury Hotel in the heart of London’s West End. It’s possible he made the decision to move closer to the front out of a sense of civic duty. Though his friends had enlisted, he was too old to be conscripted. His hopelessness grew as the war raged on.

A budget hotel aimed at mostly male clientele, the following years brought fewer and fewer visitors. Likely suffering from a similar depression to that of his brother, Joseph died by suicide on hotel grounds on 12 October 1917. It is clear for the contents of the note he left that he had convinced himself the Shaftesbury’s clientele would never return. Heartbreakingly, the war would end just over a year later.

The dining room at the Shaftesbury Hotel (© Genna Bard)

A heavy burden

It’s clear the psychological burden of industrialised warfare was badly affecting those on the home front, just as it was causing PTSD/shell shock in those who fought overseas. Those too old to sign up or be conscripted, like Joseph Fleck, could only watch as their friends were sent to the front. Many didn’t make it back home in one piece, if at all.

The Westminster inquest into Joseph’s death found “the condition of many people at the present time could only be described as on-edge” and surmised he had suffered from a “sub-conscious worry affecting the brain all the time”.

A 1950s postcard showing the Belle-Vue (© Genna Bard)

Psychoanalysis was still in its infancy, but this verdict is much more nuanced than the investigation into his brother’s “suicide whilst in a despondent state of mind” a dozen years earlier. That inquest had struggled to rationalise Andrew’s suicide as a sudden melancholia. After all, he had “never threatened to do anything to himself” prior. It would still be nearly half a century until connections could be drawn between depression and its underlying brain chemistry.

Having lost both her adult sons to suicide, Helen Fleck found their losses hard to reconcile with her religious beliefs. In her own words, she felt “the lord took everything from her by degrees”. So, aged 77, she left behind her worldly belongings and retired to the Carmelite Convent in Gillingham, Dorset. Helen adopted the name Sister Mary Teresa in her twilight years. She would pass away in the company of her fellow nuns in 1932.

The Belle-Vue photographed from Queens Road in 1983

It all ends in flames

As for the Belle-Vue, it continued to be a luxury leisure destination for a further half-century. The Edwardian ethos of taking the sea air to improve physical wellbeing fell out of fashion in the face of medical advancement and modern tourism. Holidaymakers opting for sunny overseas destinations saw the end of the Scottish Lido craze. Soon the interiors of the hotel were feeling outdated.

In 1989, the owners decided to renovate the attic rooms. Workmen’s tools sparked whilst unattended and the central roof space caught fire. No-one was injured, but firefighters futilely battled the blaze all night. By morning, the core of the building was gutted entirely.

Fire damage at the Belle-Vue (© Historic Environment Scotland)

Structurally too damaged to be saved, the Belle-Vue spent its last 17 years awaiting an inevitable demise. Though cordoned-off behind barriers, the ruins were obviously fascinating to bored rural adventurers and curious teens alike. So as not to tempt fate, the rear of the building and its interior walls were demolished. This left only the hotel’s grand façade to decay on the headland overlooking the sea.

In the end, my fanciful imaginings of winning the lottery and re-building the Belle-Vue was an impossible dream. Even so, I did find a way of bringing the place back to life. The Belle-Vue’s story is as much the history of a family as it is a building with a ‘beautiful view’. Even if the Fleck’s architectural legacy no longer stands, at least we can fondly remember the lives and achingly human struggles that shaped the place.

The Belle-Vue in its dilapidated state (© Historic Environment Scotland)

Read on…

Genna’s research into the Belle-Vue was originally published as a “Canmore in Context” article. Using images from the National Record of the Historic Environment, the series tell stories from Scotland’s most fascinating places.

You can continue your trip to the Scottish seaside at our Coasts and Waters online exhibition. There you can uncover how steamers, lidos and golf brought tourists to our coasts. For more sport and leisure, check out unique sporting venues or take a two-wheeled tour with Scotland’s historic cycling clubs.