As visitors exit the Royal Palace at Stirling Castle, they pass down a metal staircase in an unremarkable whitewashed room with a modest brick fireplace. Most visitors head straight through the doors and back into the palace courtyard without realizing that they’ve actually come through the Prince’s or West Tower. This was the residence of young heirs to the throne in the 16th century. And it played a central role in the life of King James VI and I.

James spent his entire childhood within the bounds of the castle. It was here, before this fireplace, that James gained his formidable Renaissance education from the famous humanist George Buchanan and his co-tutor Peter Young.

The castle was also the site of some of the most dramatic and violent events of James’ early life.

The fireplace at the Prince’s Tower. This is where James VI will have received his education.

Lord Darnley: Absent Father

James was the son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley. He was born on 19 June 1566 at Edinburgh Castle. Stirling would immediately play a central role in the king’s life. Stirling had been the royal nursery since at least the time of King James IV. And right away, Mary moved her son to the castle for his protection. On 22 August 1566, four to five hundred armed soldiers accompanied the litter, carrying James to Stirling Castle.

Mary ensured that James’ nursery in Stirling was decorated and furnished with bedding and other items of ‘the fynest that can be gottin’, both for him and his nursing staff.

In December 1566 Stirling hosted three days of celebrations for James’ baptism. This included lavish dinners, a hunt and a giant mock battle against a timber fort on the castle esplanade led by soldiers in fancy dress. The festivities concluded with a display of fireworks costing over £190. Virtually all the Scottish nobility and international delegates from England, France and Savoy attended the events.

Noticeably absent from the baptism was Darnley. His short-lived marriage with Mary (which had taken place in late July 1565) had wholly broken down. This was primarily due to his involvement in the murder of her secretary David Rizzio in March 1566.

James returned briefly to Holyrood with Mary in the new year of 1567. But the murder of Darnley at Kirk O’Field just outside Edinburgh on 9 February 1567 would transform both Mary and James’ lives.

Stirling Castle: A childhood home

Although many people were implicated in the murder of Darnley, James Hepburn, the Earl of Bothwell was the prime suspect. Rumours swirled that Mary was romantically involved with Bothwell and had been involved in Darnley’s demise.

After the murder, Mary transferred James to the formal protection of John Erskine, Earl of Mar, and his wife Annabella Murray of Tullibardine. James was ‘to be conservit, nurist and upbrocht within our said Castell of Striviling’. The couple had strict instructions that no one could remove the prince or approach the castle with an armed retinue.

Incredibly, Mary herself fell foul of this rule. On 21 April 1567, she arrived with a small escort intending to take James to Edinburgh. Mar feared that Bothwell might get hold of the prince or harm him. He refused Mary custody. It was the last time she saw her son in person.

As Mary returned from Stirling she was seized by Bothwell. He then coerced her into marrying him. The brief civil conflict which followed led to Mary’s capture and surrender at Carberry Hill, just outside Musselburgh, on 14 June. Mary was forced from the throne and Stirling once again became the site of a major royal event. This time it was James’ coronation as King James VI, at the Kirk of the Haly Rude just outside the castle on 24 July 1567.

Stirling would now be James’ home for the rest of his childhood. He would not leave the castle unsupervised until June 1579.

June 1579 was the first time James left Stirling Castle unaccompanied. He travelled through the North Gate to go on a hunting trip.

Stirling remained James’ official residence until late 1583 when he arranged for portions of his library and personal items to be moved to Holyrood.

School time for King James VI

Older views of James’ upbringing at the castle have painted his childhood as bleak and dour. James was terrified by his tutor Buchanan, who treated James with verbal and physical abuse.

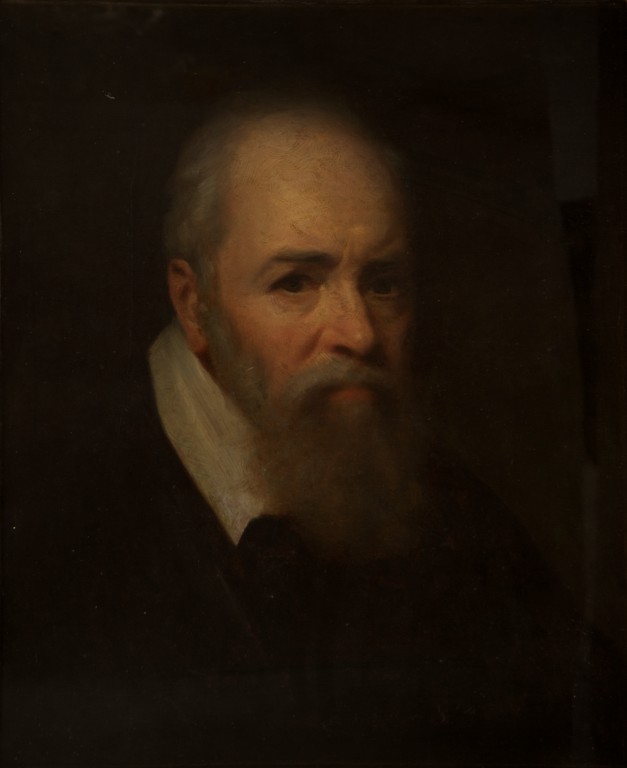

George Buchanan – the tutor who terrified young James. James had nightmares about his former tutor until the end of his life.

James detested Buchanan’s attempts to make him believe that kings were subject to the people and could easily be removed from power, as his mother had been, or even executed. He rejected this view of kingship.

James was taught a Renaissance humanist curriculum, including Latin, Greek, French, history, rhetoric, and moral philosophy. In later life he remained proud and grateful for his education, which he said made him ‘speik Latin ar [before] I could speik Scotis.’

There were many other people around James in his early life. Among them were Annabella Murray, whom James referred to as ‘Lady Minny [Mummy]’.

Although Murray had her own children and kept a formal emotional distance from the young king, she would still spend nights in his chamber settling him. He wrote his first recorded letter to her around the age of five, asking her for fruit.

James would remain affectionate and loyal to her until her death in 1603. He even made her keeper of his son, Prince Henry, in 1594.

In his first few years at Stirling James had a wetnurse, Helen Little, and six ‘rokaris’ [rockers], all of whom came from lesser noble families. Two of them, Alison Sinclair and Grissell Gray, had the dubious honour of cleaning James’ soiled nappies.

Each member of the household received food and board, with coal and candles in the winter. James, at just 20 months, received two and a half large loaves, one quart and one pint of ale, and two capons daily.

King James VI’s childhood friends

From the early 1570s, the household gradually expanded to include a range of servants, most notably the Hudson family of musicians. James Hudson received an additional payment for acting as ‘maister ballandin’ or dance master to James. By all accounts James was a very poor student.

The young King James VI.

James also shared his classroom and his fireplace with a range of childhood friends, whom he would be loyal to in later life. These included John Erskine, the second earl of Mar, Thomas and George Erskine, William Murray of Abercairny (a cousin of the Countess Mar), and Walter Stewart, a son of the provost of Glasgow.

James’ other chief tutor, Peter Young, was much kinder and gentler than Buchanan. He would remain one of the king’s most favoured servants after his departure to England in 1603, becoming chief tutor to Prince Charles. James also learned hunting and martial sports, which he greatly enjoyed and practiced in the palace gardens.

Childhood coups

While James’ domestic life at Stirling was happier and more settled than we have previously assumed, several violent events happened during his childhood which also left a mark on him. On 4 September 1571 James witnessed the bloody murder of his grandfather and regent Matthew Stewart, the fourth earl of Lennox. He was shot and killed just outside the castle by members of the nobility who were still loyal to Mary.

In March 1578, two of James’ older kinsmen, the Earls of Atholl and Argyll, convinced him to formally declare himself an adult ruler so they could remove the regent, James Douglas the Earl of Morton, from power. On 28 April a violent assault was led against Stirling by the young Earl of Mar, possibly with the backing of Morton, in protest at this coup.

In the process, James’ guardian Sir Alexander Erskine was seriously injured. And his eldest son, one of James’ friends, was killed. James is reported to have screamed and pulled out his hair at the sight of his guardian’s injuries.

This was sadly just the beginning of a sequence of violent coups and countercoups that would affect James until he emerged as a fully independent ruler in November 1585.

More on James VI

So next time you’re at Stirling and passing through the palace block, be sure to pause at the fireplace in the whitewashed tower.

Spare a thought for the little boy who sat there, and who survived a deeply turbulent childhood to become the first king of a united British monarchy, and arguably the most intellectual monarch either Scotland or England have ever seen.

Plan your visit to Stirling Castle and find out more about the stories hidden behind castle walls.

The private life of James VI was the source of gossip and speculation during his lifetime. Read more about James and his “favourites”.

About the Author

Steven J. Reid is Professor of Early Modern Scottish History and Culture and Head of History at the University of Glasgow. He has published widely on intellectual, religious, and political culture in the reigns of Mary, Queen of Scots and James VI and I. His most recent books include The Early Life of James VI (2023) and The Afterlife of Mary, Queen of Scots (2024).

Steven J. Reid is Professor of Early Modern Scottish History and Culture and Head of History at the University of Glasgow. He has published widely on intellectual, religious, and political culture in the reigns of Mary, Queen of Scots and James VI and I. His most recent books include The Early Life of James VI (2023) and The Afterlife of Mary, Queen of Scots (2024).