Doocots are purpose-built homes for pigeons or doves, known in Scotland as doos. The Anglicised alternative is dovecots.

Doocots were built from the late medieval period until the 20th century, but their construction declined significantly in the early 19th century. They were originally built to provide a source of eggs and fresh meat towards the end of winter. Pigeon droppings or guano served as a fertiliser to improve soils. Pigeon feathers were also prized for stuffing pillows and mattresses, with superstitions promising long life attached to them.

It wasn’t all good news, however. Doocots were unpopular with adjacent communities, who objected to pigeons eating their crops. In times of scarcity, the Laird’s doocot could become a focus of anger. But just as there were laws on who was entitled to build a doocot, laws were enforced against the theft and killing of these ‘tamed’ birds.

In 1741 ‘11 persons of the Gypsie gang’, who removed every single bird from the doocot of a ‘person of distinction’, were apprehended in Midlothian. They later escaped from jail in Dalkeith.

The doos and don’ts of doocots

You can find doocots across Scotland, mostly near richer arable lands, where cereal crops (which fed the pigeons) were grown. They are almost always built facing south to avoid the worst winds and let the birds roost in the sun. Normally, they were sited away from human activity. Sometimes they were at the edge of an estate, or on a vista from the main house.

Built of stone, they had to be tall enough to allow pigeons clear views of approaching predators. They had to have flight holes large enough to admit pigeons but not owls or hawks. At lower levels, stout doors prevented entry from predators like foxes and avoided ‘setting the cat among the pigeons’.

Weasels and rats were also a problem, and the many projecting stone bands or cornices on doocots were long thought to have prevented vermin from climbing up to the flight-holes. However, other sources claim the ‘rat courses’ or ledges were primarily additional perches.

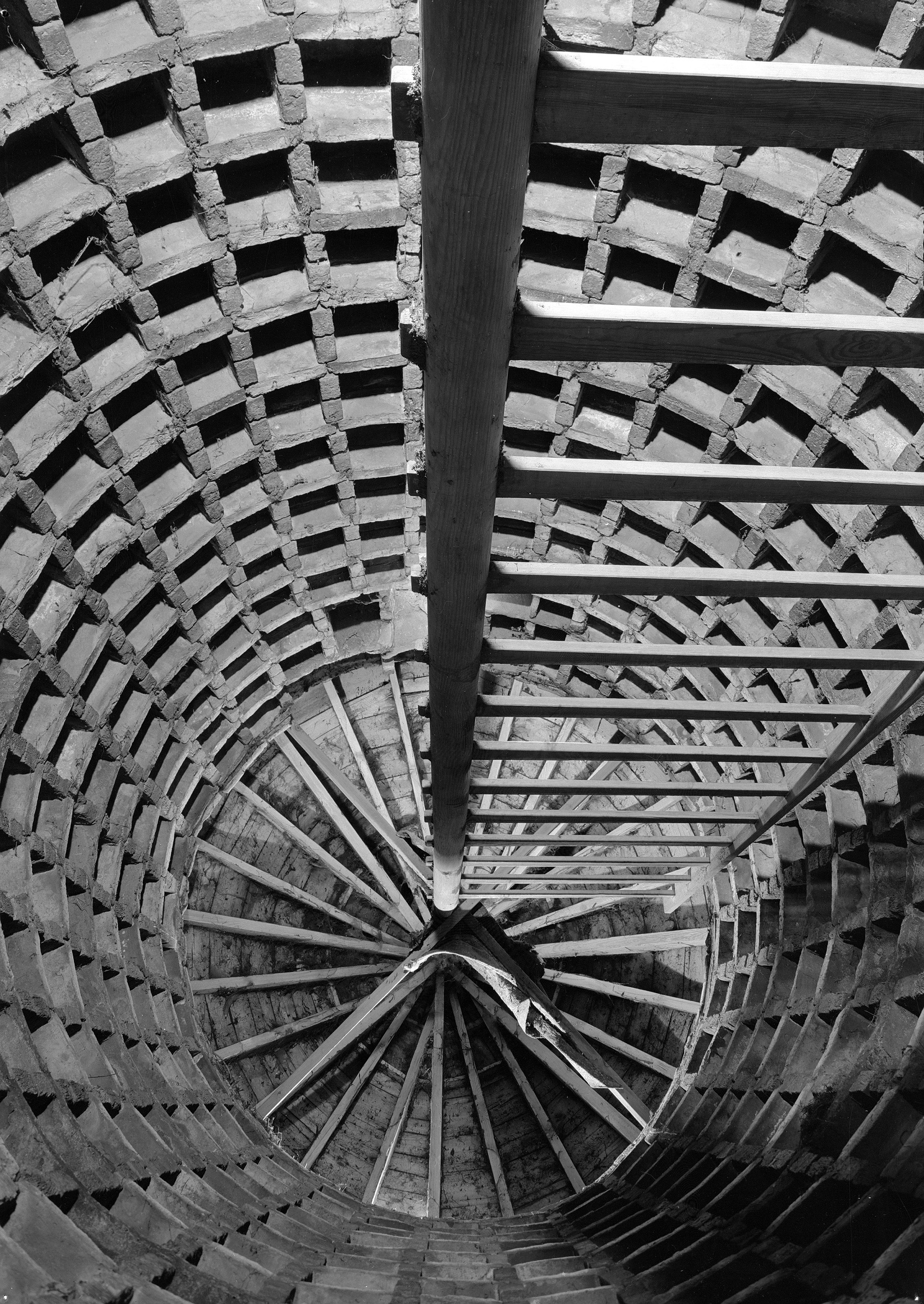

Inside, doocots have ranks of stone nesting boxes, ranging from a few hundred to Scotland’s largest example which hosts an incredible 2,400. The distinctive appearance of these nesting boxes gave rise to the term ‘pigeonholes’ for workplace letterboxes. These nesting boxes were often reached by a tall timber revolving ladder called a potence, few of which still survive.

Interior view of potence, Old Polmaise doocot. Zoom in on Canmore.

The Design Evolution of Doocots

The earliest style of a purpose-built Scottish doocot was built in the 16th century. It was circular and beehive-shaped. A good example is the 16th-century Corstorphine Doocot which is within our care. It gave its name to the famous Tapestry studios, now in Edinburgh’s Infirmary Street.

Later, the lectern doocot design became popular. Their square or rectangular base had a single, sloping roof, resembling a reading lectern. Their tall back walls allowed shelter from the wind, and crowstepped gables provided perching space for birds.

Other examples are at Westquarter, near Falkirk, with a more traditional pitched roof example at Tealing in Angus. Both of them are within our care.

A roofless two-chamber lectern doocot at Ratho Park – shows crowsteps, a ‘rat’ course, central division and stone nesting boxes internally. Zoom in on Canmore.

Aspiring landowners viewed doocots as status symbols, increasingly incorporating decorative elements such as ball-finials, plaques, windows, and recessed panels to enhance their appearance.

Another style of doocot developed as a simple tower. When architects began to get involved, their designs incorporated popular styles of the time. These doocots often featured circular, hexagonal, or octagonal shapes and were designed to match the main house, whether in classical or Gothic styles. A hexagonal doocot survives at Redhall House, Edinburgh (1756), and at Inveraray Castle the architect Roger Morris designed a circular doocot in 1747.

Dovecot at Inveraray Castle, designed in 1747 for the cost of £53. Dovecots were unusual in the Highlands due to the lack of crops to feed the birds. Find out more on Canmore.

However, not all doocots were within freestanding structures. Some examples were incorporated within existing buildings, like church towers.

The Doocot in Decline

When purpose-built doocots fell out of vogue, doocots were installed in later 18th and 19th-century farm steadings. These can be as small as just a few flight holes in a gable wall to an architecturally significant feature tower over the entrance. Perhaps the most exciting is a domed structure built in the 1760s at Penicuik House’s stables to replicate Arthur’s O’on, a demolished Roman monument.

The domed doocot at Penicuik House stables. Get up close on Canmore.

The popularity of large freestanding doocots was declining by the early 19th century, when their primary use as food stores flagged. This was partly due to new ways of taking care of animals and farming innovation which helped cattle to survive, and be slaughtered, all year round.

The increased outrage at the damage to harvests was another reason for their fall. The loss of crops to a community was a long-standing source of complaint in France, and stern laws against doocots, or Pigeonniers, were quickly adopted during the French Revolution of 1789.

Since they stopped being used, many doocots have fallen into disrepair, but their sturdy construction has made their decay and deterioration more gradual. Another reason for their survival may be the superstition that destroying a doocot would result in the death of the Laird’s wife within the year, but similar lore suggests a death sentence came from building one!

A ruined doocot in Moray. Explore more on Canmore.

Later in the 19th century, only a few new doocots were built, largely within farm steadings or walled gardens. By this date, the keeping, breeding, racing and even exhibition of pigeons was more popular than their consumption. There was a brief renaissance in Edwardian times with a few Arts & Crafts architects utilising the decorative potential of dove houses.

Today, pigeon keeping is still popular with pigeon racing lofts, the modern equivalents of original doocots, seen in gardens or the outskirts of towns and cities, though these are often built from salvaged materials.

Contemporary Reuse of Doocots

Doocots can be seen across Scotland, often as the only visible remnants of long-vanished estates. However, due to their very specific and long obsolete use, many surviving doocots are in poor and even ruinous condition.

Understandably, many owners baulk at spending money to maintain structures that have no obvious use.

Today, there are around 750 listed or scheduled doocots in Scotland. Some have decayed to the point of no return, but others are still capable of being repaired and/or reconfigured for new uses.

We maintain excellent examples of beehive doocots at our castles at Dirleton and Aberdour. There are lectern doocots at Tantallon Castle and in Corstorphine. The National Trust for Scotland maintain a picturesque example at Phantassie in East Lothian, and others are maintained by community groups.

Doo-ing them up – the restoration of doocots

Over the years there have been several repair and restoration schemes for doocots. Our grants scheme for buildings has awarded several grants to doocots in the past including a £38,400 grant to repair the Priory Doocot in Pittenweem, Fife in 2016.

Last year, Preston Tower and its doocot in Prestonpans were repaired with funding from the Scottish Government and the National Trust for Scotland. The nesting boxes are now being filled with woollen knitted pigeons, provided by volunteers.

As well as the restoration of doocots, finding a viable new use is often key to ensuring a building’s long-term survival. Due to their small size, specific purpose, and their lack of windows, doocots are often complicated to convert to other uses. Nevertheless, many doocots remain in good repair as farm or garden stores. Other more unusual uses include conversion to a water cistern at Quarrywood in Morayshire.

Several have been repaired to serve as small interpretation centres or museums, such as Blackburn House in West Lothian. The National Trust for Scotland recently restored the doocot at Newhailes as a centrepiece for their new childrens’ play-area. Also in East Lothian is Athelstaneford, a late 16th-century lectern doocot which hosts a small museum on the origin of the Scottish saltire flag. The initial repair was funded by us.

You can find a quirky new use for a doocot at the Kingsbarns Distillery in Fife. They are using the farm steading’s doocot tower to display their first whisky cask with bottles within the nesting boxes, and a signature whisky called Doocot. At Meldrum House the doocot is a candle-lit space for small whisky and spirits tasting events. There are similar plans for the late 17th-century doocot at Midhope Castle. You might know it as Lallybroch from the popular Outlander series.

Midhope Castle doocot.

Living Like a Doo

Recently our buildings team in the Planning Consents and Advice Service (PCAS) has seen a few applications to convert doocots into small residences, often as a characterful annexe to new houses. However, the conversion of doocots to residences is not new. In 1971 the renowned post-war architects Morris & Steedman converted a lectern doocot at Humbie Manse in East Lothian to a small house.

A few years later in 1974, architect Peter Allam converted and extended a lectern doocot at Ravelston in Edinburgh. Whilst in Lanarkshire a doocot at Blackwood House has been repurposed, retaining many of the nesting boxes inside. A larger lectern-style 18th-century doocot at Newliston House was converted to a residence in 1978. Again it retained many of the nesting boxes inside.

Although many freestanding doocots may not be large enough to convert to traditional homes, there is a great opportunity to convert them into unusual holiday homes or short-term letting opportunities. In Inverkeithing, a large formerly derelict B-listed lectern doocot originally associated with Rosebery House, was converted to a house around twenty years ago. It’s now available for short-term lets. Another letting opportunity is the former 17th-century doocot for East Morningside House in Edinburgh. The bedroom within the doocot also retains its original nesting boxes.

The Future of Doocots

Doocots are some of the most characterful and distinctive buildings found throughout Scotland. Although many are in poor and decaying condition, we hope to encourage their repair and highlight that there are many opportunities for their reuse. There is often a variety of grants or funding available to assist with this process.

Although their small size makes many reuse proposals difficult, it also makes their repair relatively straightforward. It’s often less costly than larger more complex buildings.

Recently, in Wales, the Spirit Cymru project has sought to use unused and underused Methodist chapels as accommodation for cyclists. Could some doocots be repurposed as small shelters or bothies for cyclists and walkers on popular routes?

There is also scope to adapt them to form interpretation or tourist information centres, birdwatching hides, or even toilets. With sensitively handled extensions they could be converted to small houses, short-term holiday lets or artists’ and writers’ retreats.

When doocots are linked to larger complexes, often within a farm steading, there is even more scope for adaptive reuse. The National Trust for Scotland’s ‘Little Houses Improvement Scheme’ had a successful rolling programme of restorations. Can a new Doocot Building Preservation Trust form to buy and convert doocots for various new uses?

Just maybe there is some scope for doocots to return to their original use as well. Recently, at the Teasses estate at Leven in Fife, sculptor James Parker has built an award-winning drystone doocot as a new home for 50 white doves.

Teasses Estate Doocot, Fife, photo courtesy of James Parker Sculpture

Doo you want more?

You love unique stories of Scotland’s architecture like this one? Then you might like to read more about the transformation story of Perth City Hall. Or find out more about the Scots who built the White House!

Sign up to our blog newsletter to get our latest stories straight to your inbox – hot off the press!