Pictish stones are being rediscovered across Scotland to this day. But what are they and why are they so interesting?

Who Were the Picts?

The Picts were a people who lived north of the Forth and Clyde rivers during the early medieval period (once known as the Dark Ages). They were descendants of native Iron Age people.

You may have heard that the name ‘Pict’ comes from the Latin ‘picti’, which means ‘painted people’. The eagle-eyed reader might then go on to notice that it was the Romans who spoke Latin. There’s a strong possibility the name started as “a slang term for the barbarian tribes north of Hadrian’s Wall” writes Jill Harden in our book, The Picts. There’s no evidence the tribes referred to themselves by that name.

Keillor Stone, near Kettins in Perth and Kinross.

In fact, the main documentary evidence we have to build up a picture of the Picts themselves is a combination of sources from their neighbours – the Romans, and monks like St Columba biographer Abbot Adomnán of Iona.

What we do have from the people themselves of course are some absolutely incredible carved stones.

What Makes a Pictish Stone?

There are a few main types of Pictish Stone. These include:

- Around 200 large, flat-faced boulders sometimes called Class I stones. We think these were created during the 4th to the 7th centuries.

- Dressed stone monuments with Christian imagery carved onto them, known as cross slabs. These are sometimes called Class II stones and start to appear from the late 7th century.

Pictish stones feature two main craft techniques:

- Incising: Fine lines are chipped into the surface, like drawing with a chisel. The result is flat, outlined imagery.

- Carving: Material is removed to create raised or recessed shapes, giving the artwork a three-dimensional look.

Inverurie 4 Pictish Stone, Aberdeenshire, has a horse incised on it.

Unique symbols

Around 40 designs have been found repeated across a range of stones and other objects. These designs are unique to the Picts and, in some cases, appear with startling uniformity across all the territory occupied by the Picts, from the Western Isles to Shetland, and from Aberdeenshire to Fife. We usually see these symbols together in groups of at least two.

Pictish symbols are early examples of the Insular art style found in early medieval Britain and Ireland (c. AD 600-900).

Archaeologists (and others!) debate the historical context in which the Picts might have developed their symbolic system. The symbols emerged early in the Pictish story and appear mainly in pairs, possibly to identify individuals.

It’s possible that the Picts painted the carved stones using minerals and plants, though they have stood outside in the Scottish weather for so many years that most traces are long gone – at least to the visible eye! However, using special equipment it has been possible to find miniscule traces of minerals on some of the stones, which might indicate that they were painted at some point in the past.

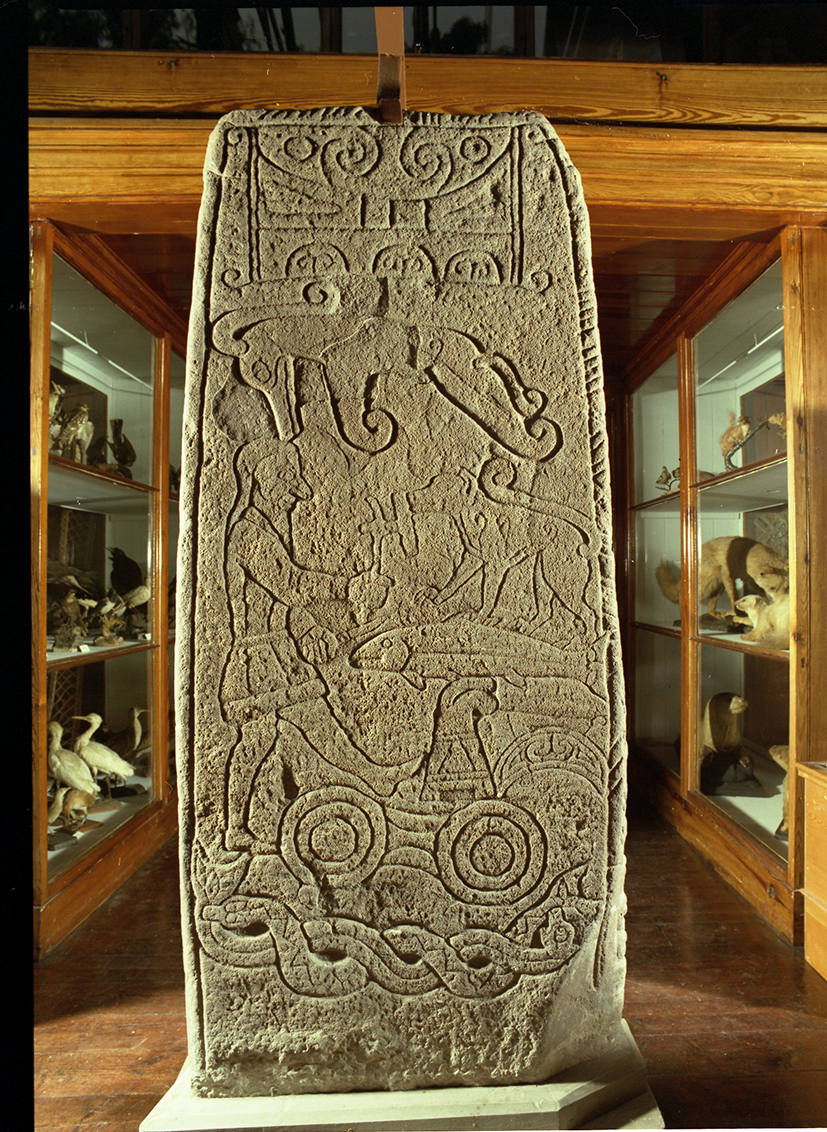

Golspie Stone, Sutherland

Brandsbutt Stone

You can find this Pictish symbol stone in the western outskirts of Inverurie. It dates from somewhere between the 7th and 9th centuries.

It may originally have formed part of a prehistoric stone circle, before being used as a Pictish monument, then built into a dyke as part of agricultural development, then reassembled into the monument we see today.

The right of the inscribed face of the stone shows the serpent and Z-rod, and crescent and V-rod symbols.

On the left a boldly-incised ogham inscription (a medieval alphabet that originated in Ireland). This ogham lettering may or may not be contemporary with the Pictish symbols. This script is interpreted as reading: IRATADDOARENS. It’s possible this is a rendering of the name Ethernan, or Adrian. While we can’t say for certain what the significance of the stone is, it’s likely to be a memorial or relate to land ownership.

Research gathered in our Statement of Significance for the Brandsbutt Stone outlines several questions about what this might mean. Some interpretations of the design system we can see here suggest the symbols represent ideas – perhaps around lineage, rank, clan, or profession. Others suggest they represent a language.

Either way the bold ogham inscription does seem to be making a big statement about the individual who we presume to be named on it.

Maiden Stone

Sticking close to Inverurie, to the northwest stands the Maiden Stone, sometimes known as the Drumdurno Stone. This is an example of a Christian cross-slab, made of pinkish granite. Its carved detail includes knotwork, spiral work and symbols.

The Maiden Stone was likely erected some time between the eighth and ninth centuries. It’s one of a very few Christian cross-slabs in Aberdeenshire and northern Pictland in general. As an explicit manifestation of Christianity, this stone has undeniable spiritual and religious value.

The front face shows a ring-headed Christian cross, with a male figure and two fish monsters above. There are numerous panels decorated with interlace, knotwork and key-pattern below this, including a circular design with spiral work at its centre.

The back face is split into four panels. These exhibit three Pictish symbol designs below a centaur and three other beasts.

One of the more popular stories about the stone is the folk tale claiming it is a maiden turned to stone after losing a bet with the devil. Perhaps more likely is that it had connections with the cult of St Medan, but more research is needed on this.

Dunfallandy Stone

The Dunfallandy Stone stands at the top of a steep slope or mound just south of Pitlochry. It’s a Christian upright cross-slab of Old Red Sandstone. It’s also known locally as ‘Clach an t-Sagairt’ (pronounced ‘Clah-ch in tack-irst’ with the ‘ch’ sound being the same as in loch) or the Priest’s Stone.

The carvings on Dunfallandy depict complex Biblical imagery, said to specifically demonstrate early Trinity iconography. An impressive Christian cross dominates the front face, with a background featuring some fantastical beasts and two angels.

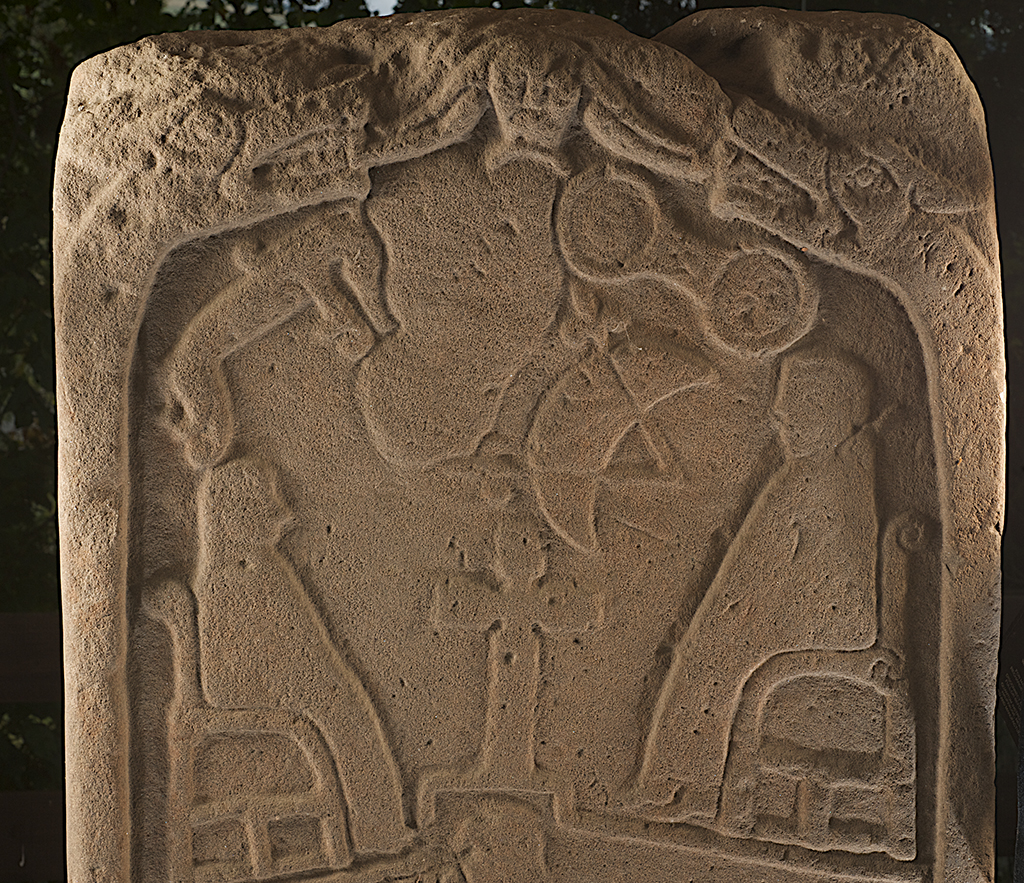

Clerics seated with a cross below a Pictish beast and other Pictish symbols on the back of the Dunfallandy Stone.

On the bottom left panel a fish-monster, is swallowing and disgorging a man – perhaps representing the story of Jonah and the Whale.

We think Dunfallandy was put up in the 8th century, although as with all carved stones it’s hard to assign an exact date. It likely stands in its original location on the western bank of the River Tummel. It may also provide evidence for the location of an early meeting or assembly place, or perhaps the location of an early Pictish church.

We don’t know who had the stone created or who carved it, but we think it was probably used as a prayer cross and was raised for an elite patron.

The foot of this side of the stone is incised with a hammer, anvil and tongs. This may indicate a person of high status within Pictish society, or who would have been useful to the monastic community.

Detail of the hammer, anvil and tongs on the Dunfallandy Stone

Sueno’s Stone

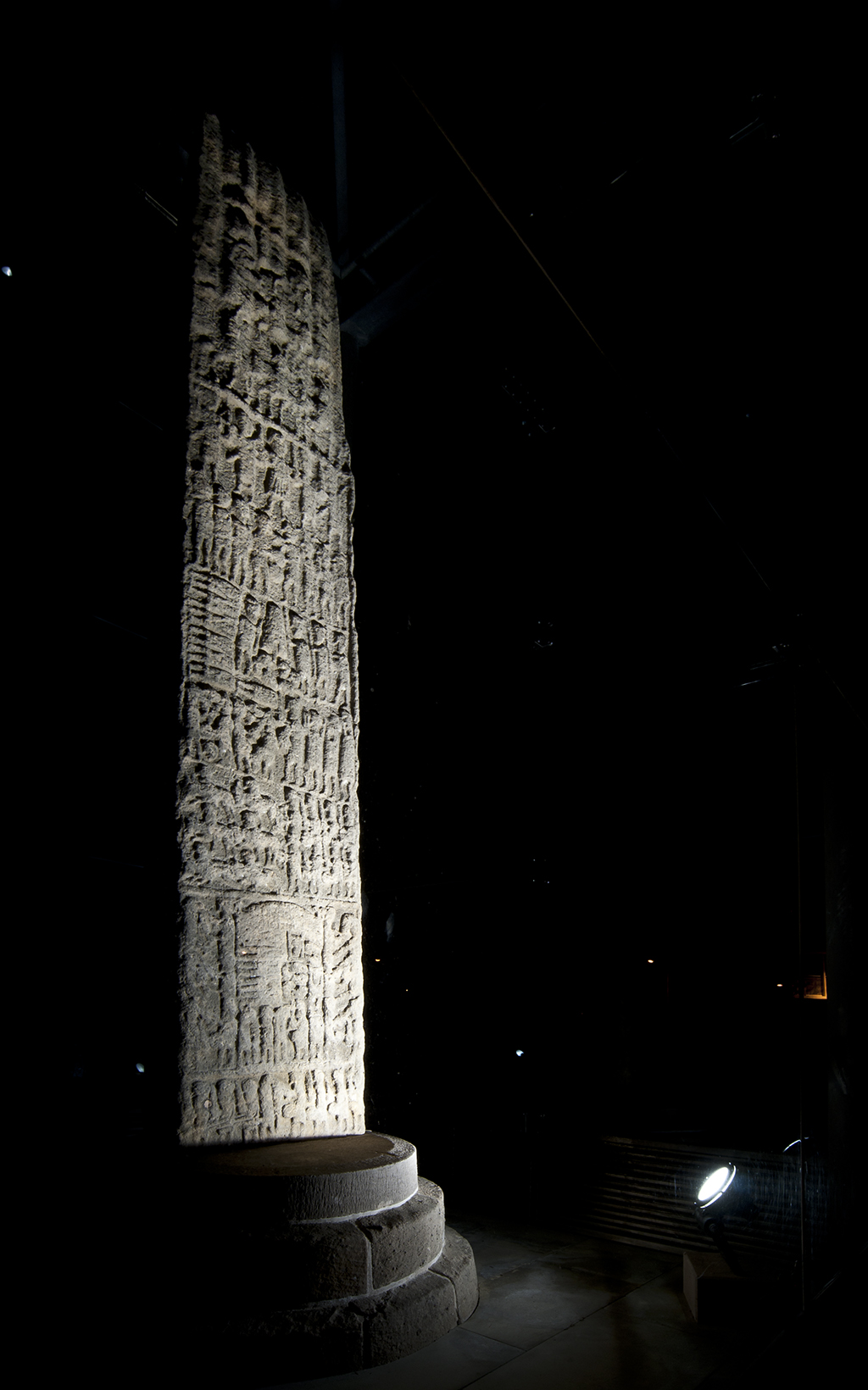

On the northern outskirts of Forres you’ll find the tallest piece of early historic sculpture in Scotland. Sueno’s Stone is a 6.5m-high cross-slab carved from a local yellow sandstone. It was likely created sometime between 850-950AD.

It shows rare scenes of battle in Pictish art. Uniquely among early historic sculptures, it may also depict a royal inauguration.

The front face is dominated by a ring-headed cross, filled with and surrounded by, interlaced spiral knotwork.

Sueno’s Stone, Forres

Beneath the cross, at the bottom of the shaft, two bearded figures face each other and stoop over what appears to be a central seated figure. Two smaller attendants stand behind them. The scene has been interpreted as a royal inauguration or enthronement.

The conflict depicted on the back is often thought to be that between Cinaed mac Ailpín, or a descendant, and the Picts of Moray. In that case, the enthronement scene is seen as the inauguration of a mac Ailpín king surrounded by clerics.

Although the stone was thought to be erected around 850-950AD, another interpretation is that it shows the battle fought by Dubh mac Ailpín, who was killed at Forres in 966. There is a tradition that his body lay beneath the bridge at Kinloss before his burial. It’s possible this bridge is perhaps shown on the stone with Dubh’s head picked out with box around it.

Sueno’s Stone is one of a relatively small number of Pictish stones that stand in

their original locations, although its setting has altered a lot. You can find out more about it in our Statement of Significance.

Places to see Pictish Stones

Hundreds of Pictish stones have been found in Scotland and we’d heartily recommend seeing as many of them as you can!

Meigle Sculptured Stone Museum is home to the largest Pictish collection in our care. It features some really diverse carvings, from one of only two known Pictish depictions of a wheeled vehicle to images once thought to depict Arthurian legend.

Panel of Meigle 11 with riders on horses, accompanied by a hound. At the end is a curious human figure with a beast’s head, holding two entwined serpents.

A collection of similar importance can be found at St Vigean’s Sculptured Stones Museum north of Arbroath. Highlights of the collection of 38 stones include a house shrine, a fragment of a huge free-standing cross and the Drosten Stone.

If you’re visiting the beautiful Elgin Cathedral, you can find a stone Pictish cross slab near the north-east corner of the crossing. It’s worth popping in to Elgin Museum whilst you’re in the area to explore their collection too.

The recently restored Ulbster 2 went on display at the North Coast Visitor Centre in 2025. A member of the public rediscovered it in St Martin’s Burial Ground in Ulbster, Caithness in 2022. As an earlier example of a Pictish stone, it dates between the 6th and 8th centuries and doesn’t show any clear Christian iconography. Its discovery after all this time reminds us there are still many secrets lying in Scotland’s historic environment!

Tell me more

For a deeper dive into the story of the Pictish people, we’d highly recommend the article ‘Who Were the Picts’ by Daniel Maclean for the DigIt! blog, which is available to read in both English and Scots.

This August, you can also head to our Celebration of the Centuries at Fort George. There you can meet some Pictish re-enactors and chat about all things Picts!

And you can now pre-order an updated and expanded version of our popular book, The Picts, from Stor, our online shop.