To tie in with this month’s theme of Royalty in celebration of 2017 being the Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology, we look at some of the lesser-known objects in our collections that may not be the most grand, showy or ceremonial, but still have an important royal tale to tell.

A stone column from the King’s Fountain

Within the courtyard of Linlithgow Palace lies the oldest fountain to survive in its original location in Britain. Built 1536-38 on the orders of King James V, the rich and intricate carvings depict mythical creatures, such as griffins, mermaids and unicorns, as well as many other eccentric looking characters.

Its aim was to impress visitors as they walked in to the body of the palace, as well as demonstrate the importance of the Scottish Monarchy (and prove to Henry VIII that James V was just as strong and powerful a leader).

Rumour has it that when Bonnie Prince Charlie visited in 1745, the fountain was made to flow with wine instead of water! Sadly, by 1746 the majority of the palace was destroyed by fires set by the Duke of Cumberland’s army and no other reigning monarch would stay within the palace walls ever again.

This stone column is an original section, which was removed when the fountain was restored in the 2000s to prevent further deterioration. The conserved fountain can be seen year round at Linlithgow Palace.

A painting to attract a bride

The story of James VI and I is a well-known tale of loyalty and shrewd ruling. He became King of Scotland at just 13 months old after his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, was forced to abdicate. The Union of The Crowns in 1603 enabled his reign over Scotland, England and Ireland for 22 years. He succeeded the last of the Tudor bloodline after the death of Elizabeth I, and at 57 years and 246 days, James’s reign in Scotland was longer than those of any of his predecessors.

The young James VI

This early and rare portrait of young James VI is likely to have been painted when the Scottish court began to negotiate with Denmark an alliance by marriage, and it is very possible that this actual picture was sent to the Danish court in order to attract a royal bride. The artist, Adrian Vanson, was Dutch and served as the Court painter between 1584 and his death in 1602.

In 1589, aged 23, James VI married Anne of Denmark, the second daughter of King Frederick of Denmark. They went on to have seven children; however only three were to survive beyond childhood, and on James’ death in 1625 his second son, Charles, who would become King Charles I, succeeded him to the throne.

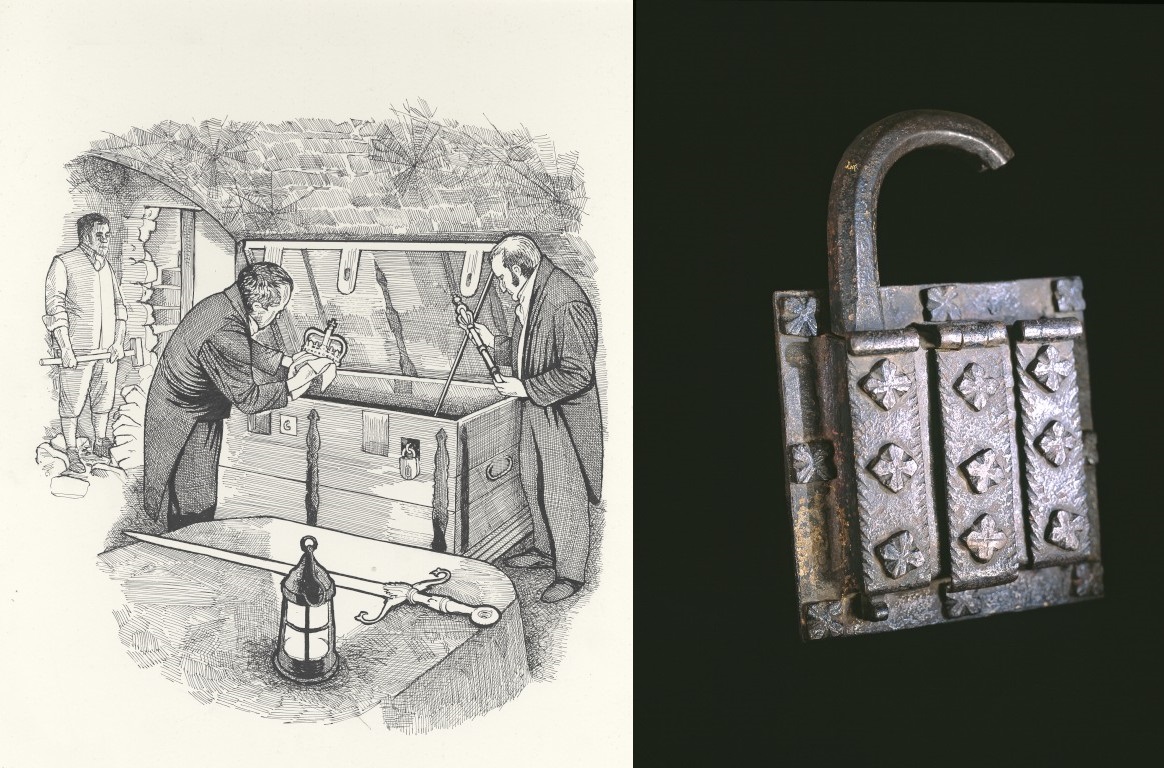

A broken padlock

Although it may look humble, this broken padlock plays an important part in the recovery of the most significant royal objects in Scottish history by one of the most significant Scottish figures in our history.

The Honours of Scotland, or the Scottish Crown Jewels as they are sometimes referred to, are the oldest surviving set of crown jewels in the British Isles. The Crown, the Sceptre and the Sword of State were used for the coronation of Scottish Monarchs from Mary Queen of Scots in 1543 until Charles II in 1641. However, under Cromwell’s rule the Honours were hidden and moved frequently to avoid being seized and melted down.

The Honours of Scotland

They were eventually discovered during The Restoration but were no longer used to crown Scottish sovereigns, and instead would be taken to sittings of the Parliament of Scotland to symbolically represent the Monarch, who, since the Union of The Crowns, was based in England.

The Acts of Union in 1770 established one, unified Parliament, The Parliament of Great Britain. When this happened the Honours became redundant and lost their symbolic role as the Scottish Parliament had been dissolved. The Honours were un-ceremonially locked within a wooden chest and stored in Edinburgh Castle. That is, until Sir Walter Scott, famed Novelist, Playwright and Poet set out in 1818 with a group of likeminded men to recover the Honours.

For over 100 years this metal padlock, along with two others, secured the great chest in which the Honours of Scotland were placed. After Scott and his men had successfully petitioned the Prince Regent to re-enter the Crown Room where the chest was kept, all padlocks were broken to gain entry. The Honours were found as they had been when first placed in the chest, wrapped in linen cloth.

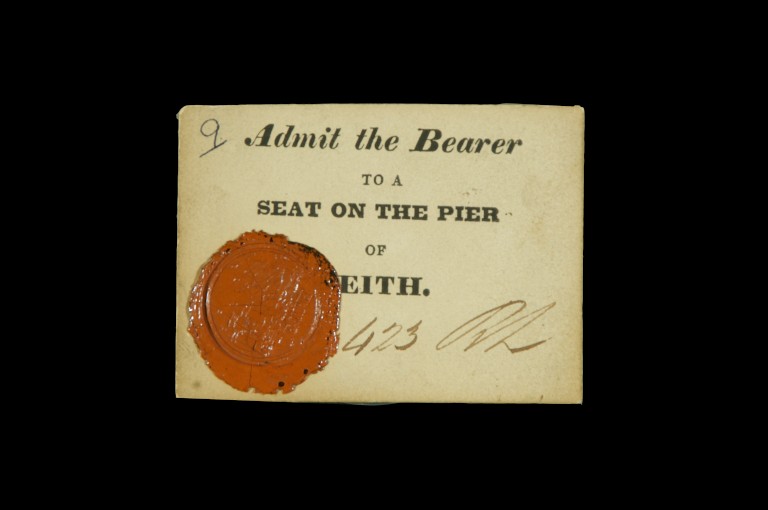

A ticket to see the king

After his success in recovering the Honours of Scotland, The City Council of Edinburgh invited Sir Walter Scott, at the request of George IV, to co-ordinate the 1822 visit to Scotland of the newly-crowned King of Great Britain and Ireland.

With just three weeks to prepare, Scott was under enormous pressure to pull together an extravagant ceremony. This visit would be the first visit of a reigning monarch to Scotland in nearly two centuries and it had to be well received. But like with the Honours, he succeeded. Due to his expert planning the event was celebrated as a huge success!

The King landed at Leith on the 25th August 1822, dressed in tartan, and ready to greet the Scots. This was the original PR event. Designed to unify the Scottish people after long periods of political and economic instability, this spectacular pageantry is widely believed to be one of the influencing factors in the kilt becoming a symbol of Scotland’s National Identity.

Numerous paintings, drawings and written accounts can be found which detail the occasion, but this little piece of social history is a tangible connection to those who were there on the day. This ticket, admitted ‘the bearer’ to a seat on the pier of Leith to watch the landing of the King on Scottish soil, and also entitles the ticket holder to ‘One Bottle Sherry’, which goes to show what a celebratory occasion this would be!

This ticket can be found on display at Trinity House in Leith.

More Collections objects that contain Royal motifs can be found in the temporary display case within the reception area of Longmore House throughout the month of February and March.