Women’s History Month has become an annual celebration in our Communications Office, but also a yearly challenge. We dig deep into our vast archives and search the records of national importance for the stories of the women who helped shape Scotland. We know they’re there, but buried beneath the well-recorded stories of Scotland’s men. Women architects, in particular, are an archival mystery.

“A woman’s place is in the home”

While the home was historically seen as a woman’s domestic domain, the role of an architect was not considered an appropriate female occupation. Why should women have a say in the design of spaces society expected them to cook, clean and live in?

But 100 years ago things began to change. Support was growing for the women’s suffrage movement. The call for equal treatment for both men and women was increasing pressure on many parts of society.

Even in 1961, this council meeting of the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland was a male dominated affair.

Throughout the 1800s, middle and upper class women had been honing their skills in sketching and creating technical drawings of buildings and structures. This was seen as an acceptable hobby for women, but the opportunity of professional practice was off still off limits.

The first women to become professional architects were sisters Ethel and Bessie Charles. In 1898 Ethel was admitted to The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and her sister followed in 1900. This move was so controversial that the RIBA Council came within one vote of revoking its decision.

Ethel Charles became the first fully qualified female architect in Britain but throughout her life she continued to meet resistance and discrimination. Few of her projects were large scale, and many of her designs were simple houses, often for female clients.

But the Charles sisters had laid the path for women to follow in their footsteps. Kathleen Anne Veitch was one of them.

What do we know about Kathleen Anne Veitch?

In a familiar story of early female architects, there’s little information on the record books about Kathleen Veitch. Her significant talent and contribution to Scotland’s architecture have all but been forgotten. Even more tragically, much of what we do know is overshadowed by her still unexplained death at the hands of an unknown assailant on the shores of the Firth of Forth.

Kathleen Anne Veitch was born on the 24 April 1907 to a tweed manufacturer in Dollar, Clackmannanshire. Her parents had been married in the Scottish Borders five years earlier and they raised Kathleen and her sister Mary Maude at Summerfield House, Hawick. Kathleen was sent to St Leonard’s School in St Andrews for schooling.

St Leonard’s School in St Andrews, where Kathleen was inspired to pursue a career as an architect.

It was at St Leonard’s that she first seriously considered architecture as a profession. In an article in the Dundee People’s Journal, she described how her “house mistress” encouraged her to pursue a career in architecture, “…having always been fond of mathematics and of colour from a purely decorative point of view”.

The advice was indicative of the more supportive attitudes towards architectural education for women in Scotland than in England. The Glasgow School of Art began to admit women around 1905 and Edith Hughes was awarded a Diploma in Architecture from Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen in 1914.

This war memorial in Coatbridge was designed by Edith Hughes.

Kathleen took her house mistress’ career advice and became one of the earliest women to train professionally as an architect.

Bright lights, big city, hitting the books

Kathleen began her studies with the Architectural Association (AA) in London in 1924. Unlike the Scottish schools trailblazing the way to equality, the AA only began to admit women in 1917.

Robert Atkinson, the head of the AA School, is quoted as airing his views on the potential of women architects:

…women would find a field for their abilities more particularly in decorative and domestic architecture rather than the planning of buildings 10 to 12 stories high.”

But by the time Kathleen passed her final exams in 1929, Elizabeth Scott, a recent AA graduate, was leading the way for aspiring female architects. Scott won the competition for the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon, and her work was described as:

The first important work erected in this country to the designs of a woman architect.”

After she graduated, Kathleen found work as an assistant with Romaine-Walker & Jenkins architects in London. In 1930, she was admitted as an Associate of the RIBA – one of only 40 women.

An Award Winning Architect

In 1930, the good news kept coming for our rising star. Kathleen was also only one of two women to be named in the list of annual architectural prize and studentship awards.

In an article peppered with descriptions of the “slim, fair-haired girl”, she described her surprise at being “awakened at midnight by a telephone bell” with the news she had won the prestigious Owen Jones Travelling Scholarship and a £100 prize.

The announcement of my success came when I was least expecting it…. I had completely forgotten that the names of the successful candidates were to be made known on the night in question, and, as I was suffering from the beginnings of a cold, I had gone to bed early.

“About twelve o’clock the ‘phone rang and a member of the staff of the West End architects’ office in which I work broke the glad news to me…

“The winning of this prize means that I get a certificate and £100. I am expected to travel abroad for not less than two months, and to bring back some drawings, sketches and a memoir. I think I shall go to Spain. I have always wanted to see Spain and I think there should be immense possibilities there for the branch of architectural work in which I am interested most.”

She made good on her word and in March 1931, she sailed with her mother and sister from London to Gibraltar on the P&O Liner, RMS Viceroy of India. She returned from her trip in May of the same year, travelling 1st class on the Kaisar-i-Hind steam ship.

Today, we hold Kathleen’s sketchbook from her Owen Jones Travelling Scholarship trip in the HES Archives. It can be viewed on request at John Sinclair House in Edinburgh.

Career Continued

After her return, Kathleen’s career was split between Scotland and London. From around 1931 until 1934, she lived in the Scottish Borders again and was employed by the Duke of Roxburgh to make improvements to his estate. She also made alterations to her family home Summerfield House in 1933. In 1935 she seems to have returned to London again.

Even while she was working away in London, she was an active member of the community in the Scottish Borders and became a member of Hawick Art Club. Her watercolours were annually exhibited along with other local talents from 1935 – 1938 and she gave lectures to the club.

Kathleen was also a keen artist. This watercolour sketch is of Melrose with the abbey in the distance.

Records only mention a few of the projects she was undoubtedly involved in. These are mostly alterations to buildings in the Borders including:

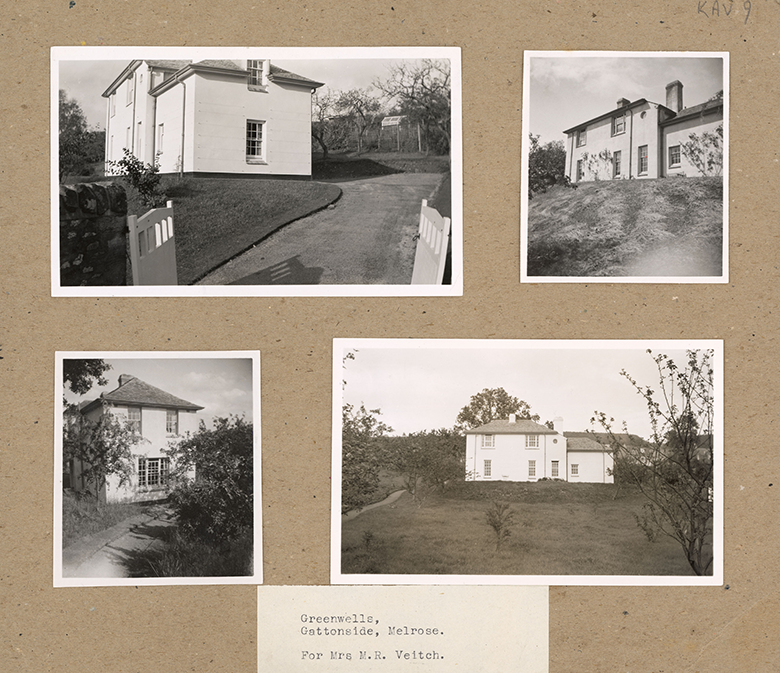

- Greenwells, Gattonside

- Barnyard Butts, Gattonside

- Kittyfield Farm, Melrose

- Mill Cottage, Earlston

Greenwells house near Melrose was designed by Kathleen for Mrs M.R. Veitch (presumably her mother, Margaret Reeve Veitch).

Kathleen never married and lived with her sister in a house she designed near Melrose.

Enjoying the sun at East Kittyfield, a house Kathleen designed and lived in with her sister. We think this is a photo of the sisters enjoying the sheltered patio.

Little Salt Hall: The house of her dreams

Perhaps the jewel in the crown of Kathleen’s career was the now C-Listed Little Salt Hall.

After being gifted part of the grounds of Summerfield House in 1937, most likely by her parents, Kathleen designed a home that combined elements of the Arts & Crafts and Moderne movements. Her plans show that she wanted to make full use of the Scottish daylight, with windows in every room overlooking the south-facing garden.

There’s a rumour that Kathleen designed a similar villa at Bemersyde, near Melrose, but we haven’t been able to discover evidence of this in the records. If you have any clues about a possible location, we’d love to know.

The interior of Little Salt Hall shows off a the unusual curved design with arts and crafts influences.

Tragic death

Kathleen was appointed an associate of The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland in 1956 and retired shortly afterwards.

Her Catholic religion mattered a great deal to her. In her retirement, she dedicated a decade to working on renovations of the Church of Our Lady and St. Joseph in Selkirk. She would often travel to Elie and Earlsferry in Fife, to attend a Catholic retreat.

On 11 March 1968, her body was discovered on the north shore of the Firth of Forth. Her fractured skull and signs of strangulation left no doubt to the police that her death should be investigated as a murder. She may have been killed the month before in late February.

A local man was suspected of her murder, but after being questioned, no charges were brought. His accidental death some time later prompted police to close the case. The full circumstances of Kathleen’s death, like much of her architectural work, remain unrecorded in the history books.

Legacy

We want Kathleen’s legacy to live on and be remembered. She made significant contributions to the built environment of the Scottish Borders and was a talent that fought against the tide to be acknowledged.

Kathleen was a pioneer of women architects and even today she would have been a minority. There are around 38,500 registered architects in Britain and only 26 per cent are women.

If you know the story of a woman architect that deserves to be in the history books, let us know.