In the early eighteenth century there was considerable unrest and political complexity in the Highlands of Scotland. The Jacobite Risings of 1689, 1715 and 1719 were attempts to restore James VII and II to the throne of Scotland.

In 1724, King George I sent Major General George Wade to Scotland to inspect the situation.

Who?

This British military commander is the only person identified by name in the United Kingdom’s National Anthem. The verse is not exactly popular in Scotland:

Lord grant that Marshal Wade

May by thy mighty aid Victory bring.

May he sedition hush,

And like a torrent rush,

Rebellious Scots to crush.

God save the King!

Following his visit, General Wade recommended to the king that the government should build barracks, bridges and roads to help control the Highlands.

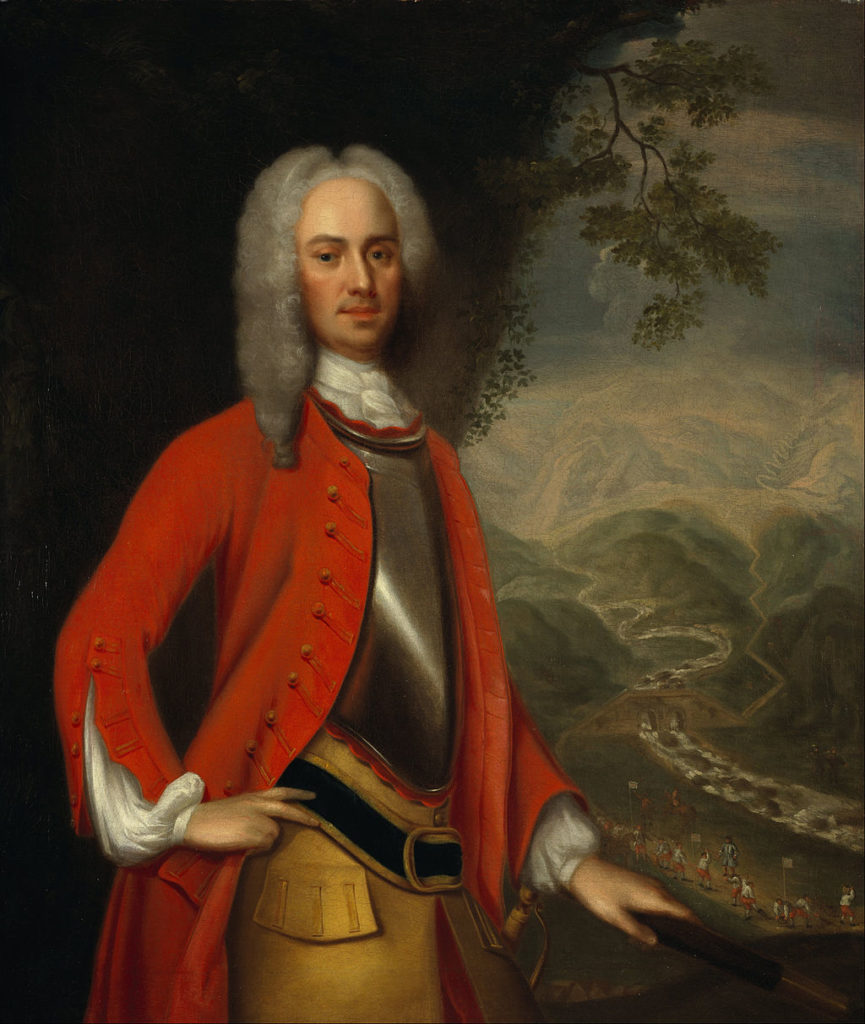

Field Marshal George Wade by Johan van Diest – Scottish National Gallery (public domain)

Wade’s World

General Wade became the figurehead of the roads programme in the Highlands, which became known as Wade’s Roads, although his successor Major William Caulfeild was responsible for the majority of the military roads built.

Between 1725 and 1737, Wade oversaw the construction of 250 miles of road and 40 bridges. These were built by labouring gangs, military engineers and estates staff. Where previously there had only been single tracks, proper roads soon appeared linking Perth, Inverness, Stirling, Fort William and Fort Augustus.

Wade’s roads included:

- Dunkeld to Inverness (the route of today’s A9)

- Fort William to Inverness (the route of today’s A82)

- Kingussie to Fort Augustus (including the Corrieyairack Pass – once the highest road in Britain)

A key focal point for Wade’s network was Ruthven Barracks, completed near Kingussie in 1721. After finishing this first phase, work was continued by his able engineer Major William Caulfeild. As Inspector of Roads from 1732, Caulfeild not only constructed a further 800 miles of road, but amended and enhanced parts of the original 250 miles. He built many more bridges, too.

Ruthven Barracks in the mist

Impact at the time

Ironically, during the 1745 rising some of the roads may have served Jacobite forces more effectively than government troops. After Prince Charles Edward Stuart raised his standard at Glenfinnan he used the road from Fort Augustus, over the Corrieyairack Pass to Dalwhinnie, to move fairly rapidly to Perth and the Lowlands.

However, the defeat of the Jacobite forces at the Battle of Culloden marked the bloody end of more than fifty years of Jacobite struggle and the beginning of a profound shift in the trajectory of British history. It set in place the destruction of the clan system and many other aspects of Highland culture and ways of life. In turn this created the social conditions in which much of the Highland Clearances took place.

The Crieff to Dalnacardoch military road runs across the bottom half of this photograph

Unexpected Legacy

General Wade’s roads and bridges played an important role in imposing the Hanoverian government’s authority in Scotland. But they also opened up routes for trade, travel and tourism.

Along the roads a number of inns – called Kingshouses – were established. Some of these survive to this day, such as the Garvamore ‘Barracks’ on the eastern side of the Corrieyariack pass. In 1773, James Boswell and Samuel Johnson were able to make an untroubled tour of the area. By the turn of the nineteenth century, Sarah Murray and Dorothy Wordsworth were among the first female tourists to document their travels around Scotland.

By the late 18th century some of the steeper and more remote sections of the military road network had been abandoned. Other sections were incorporated into the civilian road network as it was improved and expanded through the nineteenth century.

Assessing the Cultural Significance Today

We were recently asked by a local historian to assess the cultural significance of the remaining roads and bridges. To do this, we visited sections of former road that still survive as archaeological remains. We looked at sites from Crieff to Aberfeldy and onwards to the A9; from Dunkeld to Dalncardoch, and up over the moorland above Pitlochry towards Glenshee.

We saw some fantastic examples of the road and of simple, robust bridges surviving in the area. These features give us a link with people who saw them nearly 300 years ago. The history surrounding their construction was turbulent, but we can’t simply ignore markers from the past because we don’t like what they represent.

Thanks to everyone who helped us with our work to assess the cultural significance of General Wade’s Roads. These include local historian Colin Liddell, and landowners and managers in Highland Perthshire. We’re also grateful to colleagues at Perth & Kinross Heritage Trust for their help in compiling historic environment information and donating copies of their publication General Wade’s Legacy.

You’ll be able to see the results of the project in our revised online designation records, published throughout 2020.

Would you like to bring a local historic site to our attention for possible designation? Learn how on our website.