Recently, a few of us here at Historic Environment Scotland were discussing some of our favourite myths from Scottish history. Answers varied from the famous – the Loch Ness Monster – to the historical – which castles Mary Queen of Scots actually stayed in during her travels through Scotland.

Others were scary, like stories of people coming away from the grave of the Mackenzie poltergeist at Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh with nosebleeds and scratches.

My favourite example is one that is so widespread it has been enshrined into law: that the Declaration of Arbroath directly inspired the American Declaration of Independence. More on that below!

Filling in the blanks

Why do we continue to tell stories about castles or medieval documents or even monsters, which we know cannot be true? At their root myths are stories – and people really like stories.

They help us to make sense of the world and our place in it. By its very nature the past is something we can’t know everything about, and therefore we are constantly trying to fill in the blanks.

Historical myths often arise from trying to make sense of the past, and as they continue to be retold they can become the dominant narrative. In other cases, myths can also be used to reframe a historical event to better fit present beliefs.

Sometimes myths can even replace details of history we do know, because they are a better or more fitting story!

The consistent misfortune which befell the inhabitants of Cardoness Castle led to a myth that it is cursed

Myth-busting

‘Myth-busting’ has become a popular idea, extending to everything from historical facts to scientific beliefs. As you might imagine, here at HES we think a lot about remembering the past, and myths can be an important part of this.

As the examples below will show, myths often form the basis for very real commemorations and remembrances of the past. Whether or not they are accurate, they mean something to the people who believe in them enough to produce these real memorials.

Legend says this stone face at Seton Collegiate Church is that of an apprentice mason who was murdered after getting on the wrong side of his master…

At the same time, we have a responsibility to inform our members and visitors about the past with the most accurate and up-to-date information we can. One way we approach this is via exploring myth-building, rather than just myth-busting. We identify where an inaccurate myth exists, but we explore how it came to be believed.

One example of this is the myth I referenced earlier, about a supposed connection between the Declaration of Arbroath and the American Declaration of Independence.

A tale of two declarations

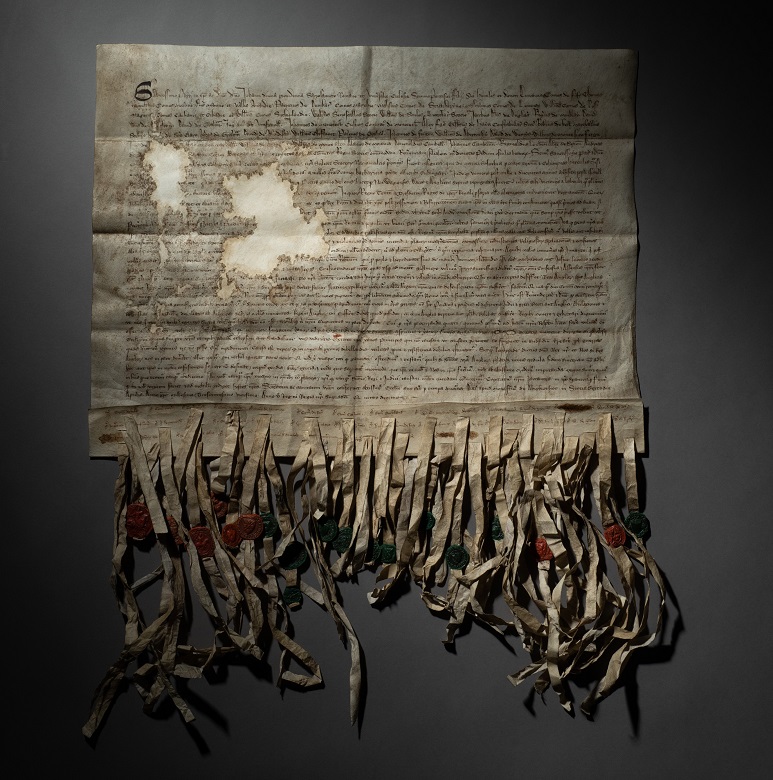

The Declaration of Arbroath is at the heart of one of Scottish history’s most enduring myths. This was created to mark its 700th anniversary in 2020

In 1998 a resolution was passed in America declaring each 6 April National Tartan Day, a celebration of Scottish heritage in America. This date comes from the Declaration of Arbroath, a medieval document that famously appears to put limits on the sovereignty of the king.

Republican Senator Trent Lott, who was largely responsible for its introduction, said

By honouring April 6, Americans will annually celebrate the true beginning of the quest for liberty and freedom… Arbroath and the declaration for liberty.”

Lott was referencing the myth that the American Declaration of Independence was directly inspired by the Declaration of Arbroath. A number of scholars devoted extensive time to disproving this, including Euan Hague in National Tartan Day: Rewriting history in the United States.

He examined the sources used by the compilers of the Declaration of Independence, as well as records of their personal libraries, and concluded,

the Declaration of Arbroath is conspicuous only by its total absence.”

A modern myth?

So where does the myth come from? It appears to be relatively new. The earliest mention I have found is from 1975, when it is mentioned in an American Scottish Clan Society’s members magazine.

The Declaration of Arbroath was dated at Arbroath Abbey on 6 April 1320

Since then it has been mentioned in a number of places on both sides of the Atlantic from Westminster to an American late-night television show Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson. It’s in popular history books, and in the Resolution for Tartan Day.

I have previously suggested that this may come down to an issue of naming. From about 1800 until relatively recently the Declaration of Arbroath was often called the Scottish Declaration of Independence. Thus, the two perhaps became conflated in people’s minds.

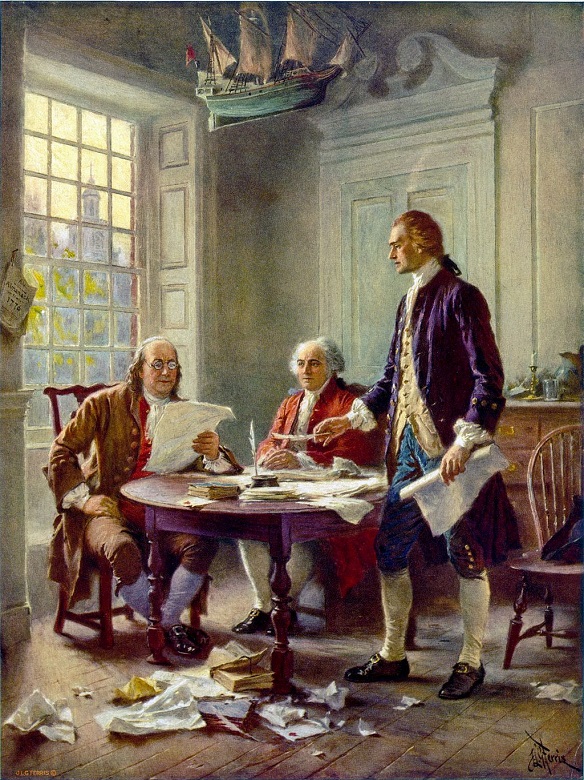

Of course, as will all myths there is an element of truth here. The Declaration of Arbroath was one of a number of medieval documents that helped contribute to ideas of proto-democracy. But we can safely say Thomas Jefferson did not have a picture of it hanging in his study as he drafted the Declaration of Independence.

A depiction of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and Thomas writing the Declaration of Independence by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (Public domain via Wikipedia Commons)

Quickfire Myth-busting!

Below we’ve applied some quickfire myth-busting to some more of our other favourite common myths and stories:

Did a spider really inspire Robert the Bruce to continue his fight for the Scottish crown?

Probably not. This story was popularised (and possibly made up) by Sir Walter Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather

Were there really mer-people between the Hebrides and the Mainland?

No. “The Blue Men of Minch” were said to swim this stretch of water looking for sailors to drown. This helped explain the losses of life in dangerous stretches of water.

View from Rubha Reidh Lighthouse out to the Minch

Did the Picts paint themselves blue before going into battle?

Maybe. There is some thought that this is the use of woad on their skin, possibly as a tattoo or an ointment. But there are also lots of historians who say there is no strong evidence of the popularity of the use of woad. This is one myth we may never be sure about!

Got a favourite?

What are your favourite myths (or stories you suspect are myths) from Scottish history? We’d love to hear them!

Watch the livestream!

Did you miss our livestream? Don’t worry – we recorded it for you. Watch it now.