A forgotten monument to a hidden chapter in British-African history stands at the edge of the car park at Larbert Old Church, Stirlingshire.

Known as the ‘obelisk’, it commemorates James Bruce. He was an enigmatic explorer, a descendant of Robert the Bruce and, for a time, an Ethiopian courtier.

James Bruce of Kinnaird (1730-1794) was a man whose legacy has been largely misunderstood over the centuries.

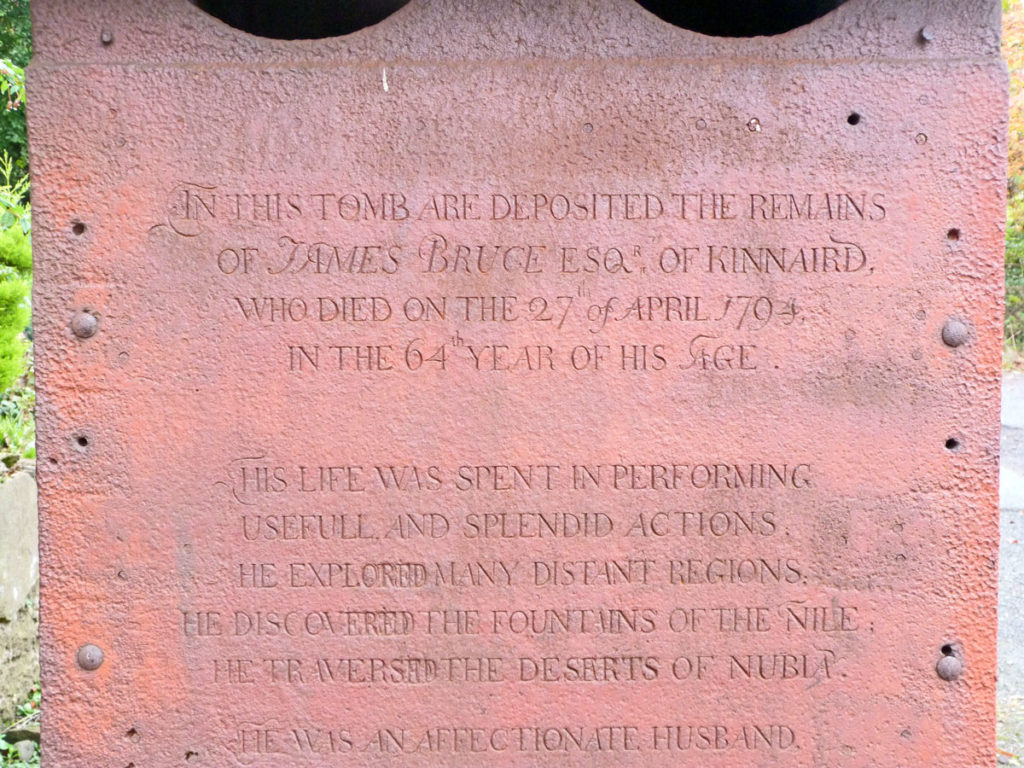

Bruce spent four years in Africa, from 1768 to 1772, and his time there is briefly summarised in an inscription on the monument:

‘He explored many distant regions./ He discovered the fountains of the Nile’ .

Like many commemorative monuments, it doesn’t tell the whole story.

Finding the source of the Nile was a geographic puzzle that fascinated Europeans. But, as Bruce himself acknowledged, Ethiopians already knew where it was. Additionally, another European had beaten him to the real claim 150 years earlier.

I believe Bruce’s ‘discovery’ is likely a misleading cover story. it’s possible James Bruce was on a secretive, personal mission to Ethiopia to locate a sacred religious relic, the Ark of the Covenant.

The Grand [De]Tour

The ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe was an educational rite of passage for 18th century British aristocrats. Most would return with drawings of Roman and Greek antiquities.

Bruce’s tour, however, seems to have stimulated an enduring passion for Africa.

After promising King George III drawings of African antiquities, he planned a ‘Grand Detour’ to Ethiopia.

A Closed Country

A century earlier, the Portuguese Jesuits had tried to convert the already-Christian Ethiopians to Catholicism. Interpreting this as an attempt to colonise Ethiopia, Emperor Fasilides exiled the Jesuits. He closed the borders and prohibited further outside influence.

Having taught himself Ethiopian languages (including the language of the royal court, Tigrinya), Bruce embarked on a perilous journey into the closed country.

James Bruce was born at Kinnaird House. © Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

The explorer apparently charmed and gifted his way through a land usually hostile to foreigners. On his black horse Mizra, Persian for ‘scholar’, he trekked across treacherous terrain and Ethiopia’s flat-topped mountains. He brought a telescope so large it required six men to carry it.

Bruce arrived at Ethiopia’s imperial capital Gondar during a smallpox epidemic. His knowledge of medicine gained him entry to the court – where he would remain for almost a year.

A Mutual Understanding

After curing the royal family of smallpox, Bruce was appointed Lord of the Bedchamber. Thanks to his ginger hair curled and perfumed in the ‘Ethiopian fashion’, Bruce was a baalamaal – a court favourite. In this role, he had a unique insight into the tumultuous politics of Ethiopia.

A Protestant Scot, Bruce bonded with the Iteghe, the Queen Mother, over their shared distrust of Catholics. He befriended the Machiavellian Regent Prince Ras Michael – and fell in love with Ras Michael’s wife, the beautiful Princess Esther.

James Bruce had relationships with many women in Ethiopia, including the Princess Esther. He later described this period as “one of the happiest moments of my life”. Image courtesy of the Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Ethiopian Emperors were the King of Kings and traced their lineage back to the biblical Queen of Sheba and King Solomon. At court, Bruce boasted of his own lineage, declaring:

“My ancestors were the kings of the country in which I was born, and to be ranked among the greatest and most glorious that ever bore the title of king.”

Shared symbols

Before Bruce left Gondar, Ras Michael gave him a collection of Ethiopian manuscripts to share with the monarchies of Europe. From these, Bruce composed a history of Ethiopia designed for a European audience: Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1790).

One of the manuscripts was The Chronicles of Aksum which references the Ark of the Covenant, a sacred chest containing the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments. According to legend, it had been carried from Jerusalem to the ancient Ethiopian Highland city of Aksum by ‘red headed angels’.

It’s possible this manuscript was a personalised gift for Bruce. It was adorned with a lion’s head and a bow and arrow, crossed in the shape of a saltire cross. The lion is a shared emblem of royalty in both Ethiopia and Britain.

The four cast iron lions of Bruce’s monument mark it out from the other obelisks in the adjacent churchyard. They were likely an acknowledgement of his time at the Ethiopian royal courts.

The Ark at Aksum

In January 1769, Bruce went to Aksum himself. He arrived in time for an important religious celebration in the Ethiopian calendar.

During Timkat, the Tabotat – a representation of the Ark – is brought out, covered in cloth, and paraded by priests. The Tabotat is then returned to the church, unseen for the rest of the year.

Bruce scarcely mentions Aksum in the account of his travels, but the city could have held a special importance for him as an antiquarian, an academic Freemason and a member of the Bruce family.

The Rome Stele (also known as the Aksum Obelisk) © I, Ondřej Žváček, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

A Monumental Influence

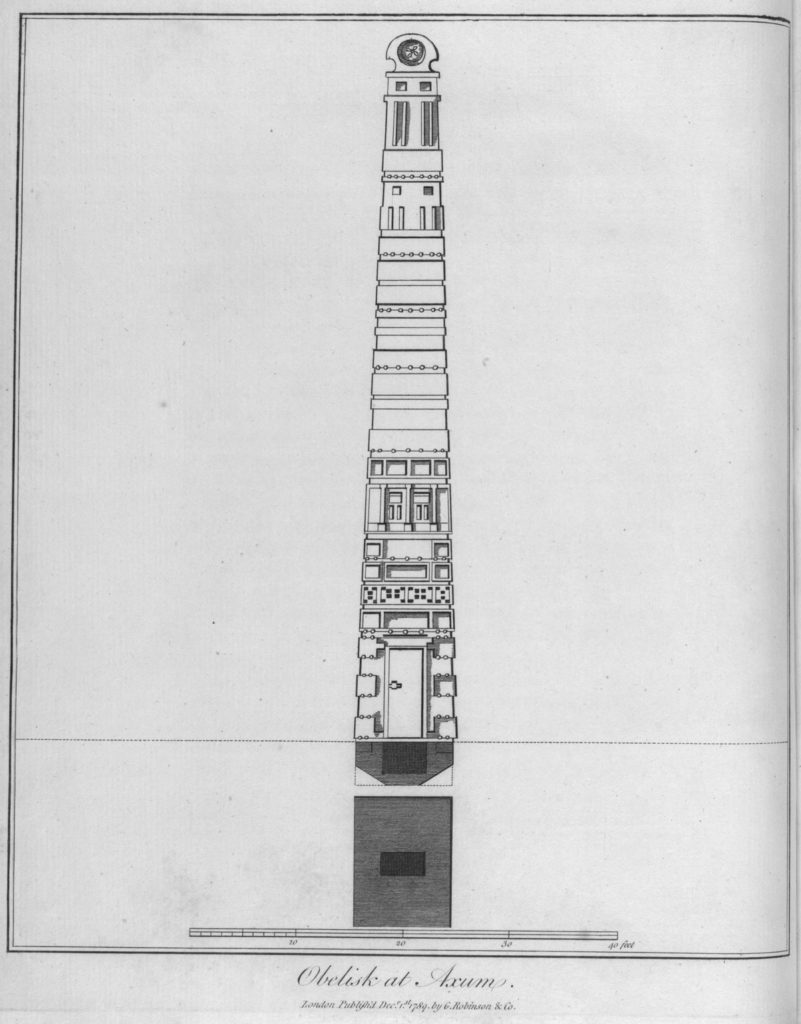

In 1772, Bruce returned to London. As promised, he presented his drawings of African antiquities to George III. Among these was a depiction of the ‘Obelisk of Aksum’ – an Aksumite ‘stele’.

These gigantic monolithic monuments, similar to obelisks in appearance, mark the tombs of ancient Ethiopian nobility and royalty. Constructed in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, the Aksumite stelae are towering testimonies to a forgotten African Empire which rivaled Ancient Rome.

Detail of an Obelisk at Axum,in Bruce’s Travels, drawn by James Bruce (or possibly Luigi Balugani) © National Library of Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Bruce’s tales of Ethiopia, recounted at dinner parties and gossiped about in letters, were met with disbelief. He became a figure of ridicule, mocked by contemporaries such as Samuel Johnson and James Boswell. Ultimately, he would be laughed out of London.

There were, perhaps, ulterior motives for Bruce’s rejection by ‘polite’ society. In her book Plotting To Stop the British Slave Trade: James Bruce and His Secret Mission to Africa (2019), Jane Aptekar Reeve reveals that Bruce belonged to a secret network of British slave trade abolitionists.

The Scottish cartoonist Issac Cruikshank made James Bruce a caricature, depicting his story of the “Abyssinian Breakfast”, in disbelief of Bruce’s claims that Ethiopians took live cuts of meat from cattle. This was later proven to be true. Image © National Portrait Gallery, London. NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

In London, Bruce was accused of not being the author of his drawings. The mysterious disappearance of his companion artist, Luigi Balugani, on the return journey from Ethiopia did not help his case. As a result, the King ordered his drawings to be hidden from view.

To add insult to injury, in 1805, the English Egyptologist and artist Henry Salt retraced Bruce’s footsteps. He redrew the Aksumite antiquities and his romanticised drawings of the African ruins were well received in Britain.

The obelisk at Axum, painting by Henry Salt and Daniel Havell, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The James Bruce Monument

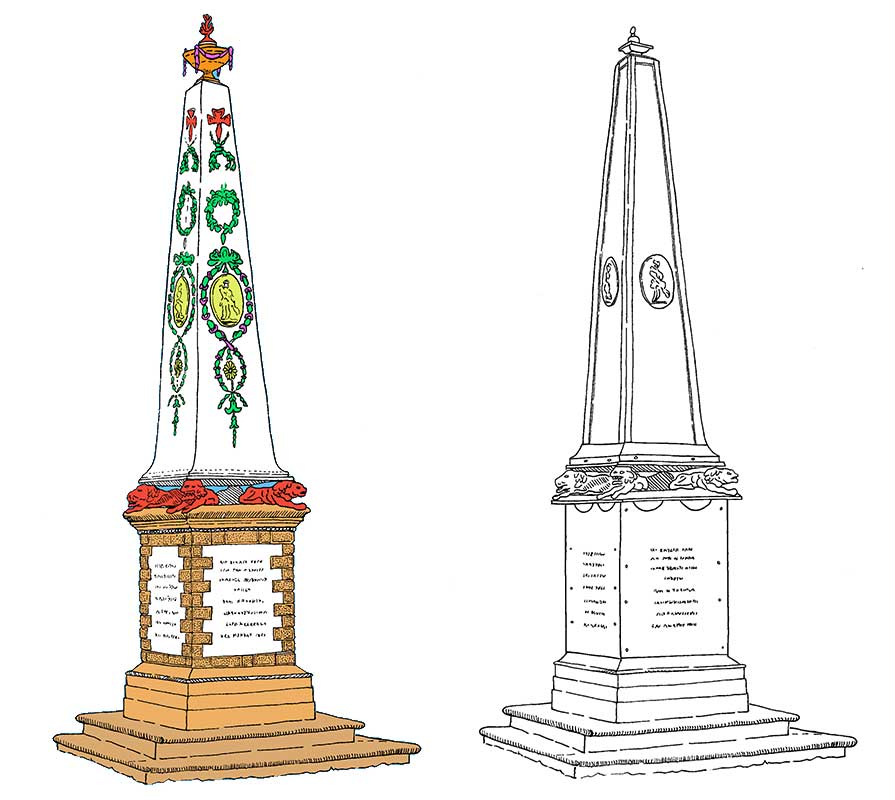

In 1785, Bruce commissioned his cast iron monument in memory of his wife, Mary. It would stand in the Bruce family plot at Larbert churchyard overlooking the Stirlingshire landscape that reminded him of Ethiopia.

Manufactured by the Carron Company, it was one of the earliest cast iron obelisks in Britain, and a technical marvel in its day. In 1787, Robert Burns made a point of seeing the ‘fine monument in cast iron’.

After a lifetime of adventure, Bruce was to suffer death by misadventure in 1794. Ever the gallant, rushing to accompany a woman to her carriage, he had a fatal fall down the stairs of his Stirlingshire home.

When it was first built, the Bruce Monument was a striking and colourful sight. The images here reveal how the obelisk changed between its erection and 2010. © Geoff Bailey, Falkirk Local History Society

By the beginning of the 20th century, Bruce’s monument was in a lamentable state of decay. In 1902 the Falkirk Herald contrasted the ‘scandalous’ neglect of Bruce’s monument with the enthusiasm shown towards Roman ruins in Scotland. A revival of Scottish nationalism in the early 20th century resulted in the monument’s restoration, which was completed by 1911.

However, after being moved from its original location in 1993, a crane returning the obelisk failed to reach across the wall to its stone mount in the churchyard. The monument was rather unceremoniously deposited at the edge of the car park.

In August 2023 the obelisk was removed for conservation, which was part funded by a grant of £32,500 from Historic Environment Scotland. Once the conservation is complete, the plans are to reinstate it at the Kinnaird family tomb in Larbert Old Parish Church graveyard.

Remembering Bruce

Today, the obelisk is a shadow of its former self. Once brightly painted, its time-worn surface has now rusted into a reddish hue. Its intricate detailed decorative plaques bearing Greek inscriptions have faded over the centuries.

The neglect and displacement of Bruce’s memorial obelisk by the end of the 20th century is symptomatic of his story, as a man whose messages were distorted upon arrival in Britain.

Listed at Category A, of historic interest and as a fine example of an 18th century cast iron obelisk, Bruce’s obelisk is a distinctly Scottish ‘stele’.

I personally believe it deserves to be restored to its original state and context. In the current context of re-evaluating British colonial history, it provides important insights into a little-known episode in Scottish-Ethiopian relations.

Antonia Dalivalle is an independent researcher currently working in the fine and decorative art market in London. Antonia’s research into James Bruce uncovers a hidden chapter in the history of British-African relations. She aims to chart the legacies of a relationship between an individual and an independent African country – legacies which appear in unexpected places. What is Ethiopia’s influence on local Scottish history?

Antonia Dalivalle is an independent researcher currently working in the fine and decorative art market in London. Antonia’s research into James Bruce uncovers a hidden chapter in the history of British-African relations. She aims to chart the legacies of a relationship between an individual and an independent African country – legacies which appear in unexpected places. What is Ethiopia’s influence on local Scottish history?

Note: this blog was updated in April 2024 to include information on the restoration of the James Bruce Obelisk.