It’s Ask A Conservator day! This is your chance to get to grips with how historic places, monuments and objects are cared for.

From caring for objects and buildings to historic paintings and paper, our conservators work against the clock to stop time, chemistry and gravity decaying Scotland’s history.

For #AskAConservator day some of our conservators have answered your questions.

Discover their adventures and challenges, from investigating a medieval lead casket believed to hold Robert the Bruce’s heart to putting historic objects in the freezer…

What is conservation?

“Conservation means to preserve or look after something. HES collections staff mainly carry out preventive conservation. This means trying to control environmental factors that may cause historic artefacts to deteriorate. It includes temperature, relative humidity, light levels, housekeeping and pest management.”

Lynsey Haworth, Collections Access Manager

Collections Access Manager, Lynsey Haworth, cleaning one of the Stirling Heads in the Kings Presence Chamber, Stirling Castle.

Why is housekeeping/conservation cleaning important?

“Dirt and dust on historic artefacts can led to a wide range of problems. If the relative humidity is high these particulates can stick to objects and be difficult to remove. Dirt can have an abrasive effect on objects and leave scratches. Dust and dirt can also act as a food source for insect pests.”

Lynsey Haworth, Collections Access Manager

What’s the difference between restoration and conservation?

“Restoration is the return of an artefact to a perceived notion of how it looked at some point in its existence, usually its ‘original’ appearance.”

“Conversely conservation does not attempt to restore lost details, but to halt the progress of decay and deterioration. At its simplest conservation attempts to halt the effects of time whilst restoration attempts to reverse them (visually at least).”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

So why conserve and not restore?

“The issue with restoration is it requires reconstruction of elements that we may have no evidence for, so can be speculative at best. This process can change our perception of objects and their purpose, obscuring what may in fact have been their original appearance and significance.

“An example is that classical statuary was originally restored by being deep cleaned back to fresh-looking marble. Unfortunately, this removed tiny fragments of pigmentation that showed statuary throughout the classical world was in fact painted in bright, even garish colours.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

What’s been your biggest conservation challenge?

“Dealing with previous conservation attempts where inappropriate materials or techniques have been used. These can often prove problematic if necessary to remove at a later date. Removal could potentially cause harm to the object or structure.

“They can also influence what materials can be used in future interventions, however people were often using what was available or a ‘trend’ at the time, with the best intentions. E.g. use of wax as a consolidant to treat lime based wallpaintings or oil paints to ‘inpaint’ an oil painting rather than a more reversible medium.”

Ailsa Murray, Paintings Conservator

“Conservation’s biggest challenge is always the same; it is the unnatural war against entropy. Trying to stop materials deteriorating against the combined actions of time, chemistry and gravity. Do you like a challenge?”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

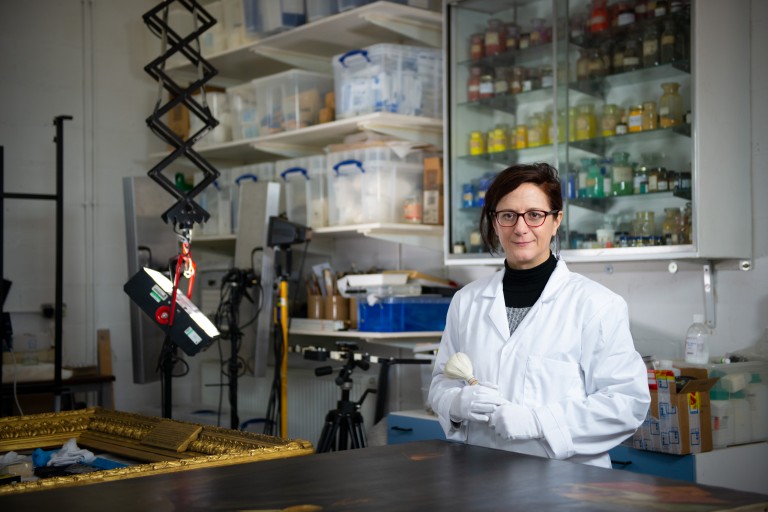

HES Paintings Conservator Damiana Magris at work at the South Gyle Conservation Centre, Edinburgh.

What’s a typical day like for a conservator?

“The job is a very varied one and dependent on the task being carried out can entail sitting in an office carrying out research and writing reports, lying on your back injecting statuary 70ft up a scaffold, encased in PPE carrying out moulding and casting, or recording Viking graffiti within a Neolithic tomb …at night.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

Inner casket for Robert the Bruce ‘s heart.

What’s the most unusual thing you’ve cared for?

The Infra-Red examination of a painted Egyptian Coffin at National Museums Scotland, a paint investigation of The Dunmore Pineapple building, Forthside, and a paint investigation of original Edinburgh North Bridge street lamps.

Ailsa Murray – Paintings Conservator

“I was involved in the investigation of the medieval lead casket believed to hold Robert the Bruce’s heart. That’s probably the strangest…so far.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

What is the strangest project you’ve undertaken?

“Probably working on my own in Maeshowe Chambered Cairn for three consecutive nights, digitally recording Viking graffiti.

“This entailed the transportation of all the necessary equipment through the 1.3m high x 20m long entrance passageway, before commencing an 8pm to 6am shift.

“It was quite a privilege to spend so long within such an extraordinary space, which some archaeologists believe was originally created as a liminal space between our physical world and the afterlife.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

Stone Conservator Colin Muir at South Gyle Conservation Centre.

What’s the oldest thing you’ve ever conserved?

“In my present role, probably Neolithic stone ‘furnishings’ within Skara Brae, which date from around 5000 years ago, some even had decorative geometric designs cut into them.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

Do you ever come across skeletons?

“I once come across human bone fragments working in a sea cave. Such human remains need to be reported to the authorities and museum to be dated and can lead to police site investigations, or wider archaeological excavations. Thankfully this material turned out to be of Neolithic origin.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

What is the most difficult thing to treat?

“Salt-contaminated objects. Sometimes they can be desalinated and protected from further decay, but in some rare cases the damage has already been done, and the internal crystallisation of salts has turned a piece of stone into a pile of salty stone dust. There is absolutely nothing can be done in this instance other than take samples and record photographically. We strive to never let that happen to any of our artefacts.

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

What is the biggest conservation project you have been involved with?

“Probably the conservation of the external elevations of the renaissance palace block at Stirling Castle in 2007. These facades are richly covered in decorative stonework and statuary, and required every centimetre of the surfaces to be wet-brush cleaned by our team of four, before conservation treatments could even begin!”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

Painting Conservators Ailsa Murray and Damiana Magris, working on the cleaning and restoration of the James VI and I birth room painted wood panels, in Edinburgh Castle

What part of being a conservator do you love the most?

“I love being in intimate contact with an original object and investigating its history and how it was originally made.”

Ailsa Murray – Paintings Conservator

“Dealing with newly discovered artefacts and sites is always exciting, and getting access to isolated, hidden or elevated locations not many see is particularly so.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

A selection of equipment used by our collections team to help monitor and control environmental conditions in display and storage spaces.

How do you clean historic artefacts?

“We have a wide range of conservation equipment which we use for cleaning our historic collections. These include microfibre cloths, soft brushes, and specialist hoovers which have an adjustable suction for when working with very delicate items.”

Lynsey Haworth, Collections Access Manager

How do insect pests damage historic artefacts?

“There are several types of moth and beetle that are called ‘museum pests’ because they are known to eat historic collections! It’s usually the larvae that do the most damage. Holes in textiles, wood and other organic materials are often an indication that something has been nibbling.”

Lynsey Haworth, Collections Access Manager

How do you control pest problems?

“We use traps to capture insects in display and storage areas to help get an understanding of what beasties are around. A full trap can often be an indicator of a wider problem. If we suspect an active pest problem, we will usually put the object(s) thought to be affected in a freezer unit. -30c for 72 hours will kill off all stages of the insect lifecycle.”

Lynsey Haworth, Collections Access Manager

What advice would you give to someone starting out?

“Be open minded about the particular discipline you’d like to specialise in. There is often more work opportunities around in some disciplines rather than others but ultimately you have to follow your heart.”

Ailsa Murray – Paintings Conservator

“Don’t waste time! Most people in my day came late to conservation through a variety of secondary routes. In my case sculpture conservation was never suggested to me a as career choice, either at school or art college.

“If conservation is an area that appeals, I recommend applying directly for an undergraduate mixed conservation course. This will give you an early start in the profession and allow you time to sample different disciplines before deciding on your eventual specialism.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

How did you become a conservator?

“I came from a Fine Art background, initially studying painting and drawing then having had the opportunity to work with a conservator locally I decided to undertake a post-graduate course in the Conservation of Fine Art, Easel Paintings.”

Ailsa Murray – Paintings Conservator

“My initial training was in Fine Art as a sculptor, and eventually led to me undertaking a post-graduate MSc in Architectural Stone Conservation.”

Colin Muir, Stone Conservator

What will conservation look like in the future?

“Who knows, particularly living through times like we currently are experiencing. I hope it is a positive future as people find solace in tangible objects and structures from the past in times of uncertainty.

“As we are already moving towards a more preventive approach, I can imagine this will progress further in this direction. Although I do believe there remains a place for more interventive treatments where necessary or applicable particularly if we are not to lose valued and specialist skills which give purpose to life.”

Ailsa Murray – Paintings Conservator

Our conservation science, digital documentation and digital innovation teams work with cutting-edge technologies in our conservation centre, the Engine Shed

Learn more about our work in conservation, keep up to-date with the latest projects in our blogs, and find out more about building conservation, conservation science and digital documentation at our dedicated conservation centre, the Engine Shed.