I grew up thinking weaving was traditionally men’s work, but I was completely mistaken. When I was a child, I knew crofting men in blue boiler suits who inevitably had a loom in one of their sheds.

Weaving’s women’s work

On the Island of Berneray, where my dad is from, the census records from 1841 to 1901 only list one man as ‘weaver’. All the others are either quaintly called ‘weaveress’, or ‘weaver’s apprentice’, and the latter are all girls.

Here’s my dad reminiscing about his mother’s work.

‘After my brother and I started school, my mother could take on plenty of work: she often got wool in lieu of payment, and when she had time, she used to dye it and then card and spin it. This work was known as calanas. The weaver made the cloth for her, but she herself laid out the design on the warping frame in the weaver’s house.’

The very spinning wheel Peigi’s grandmother used © Peigi MacKillop

Looms

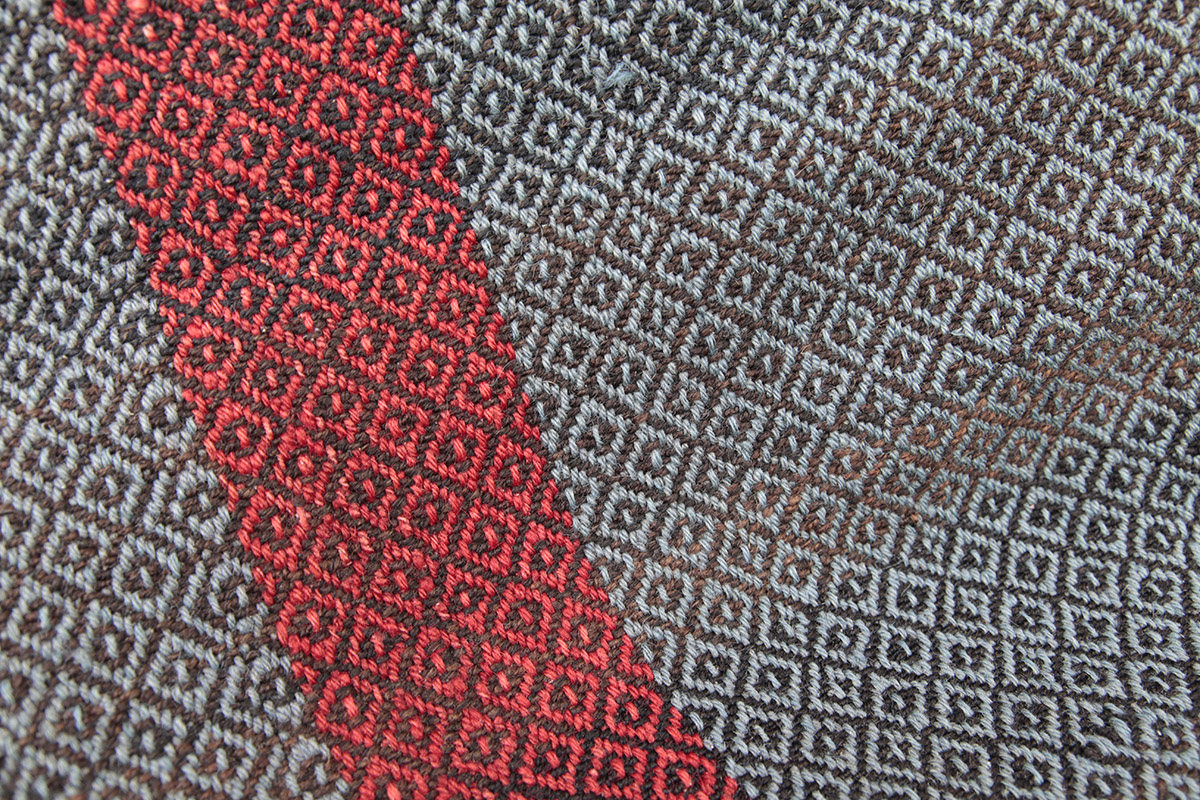

The result of this was the blankets pictured here, brightly coloured and detailed.

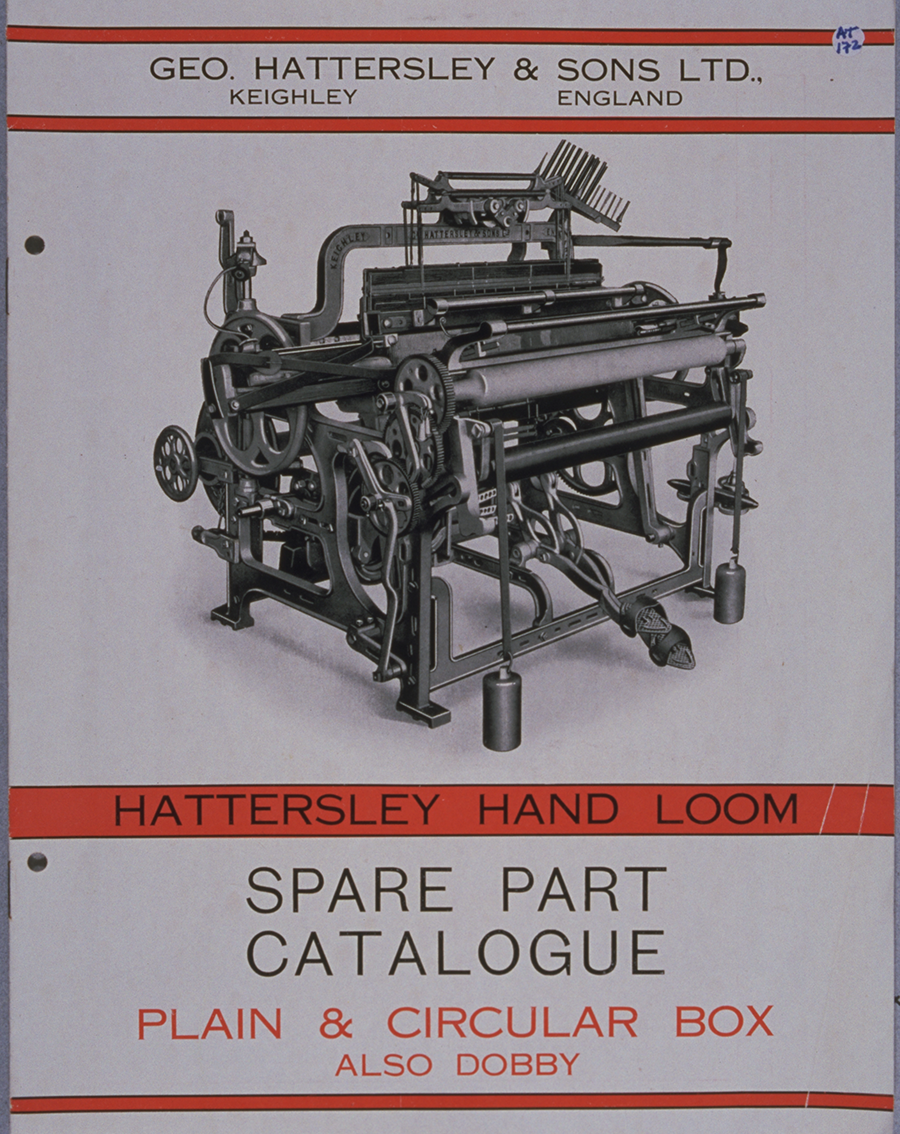

In the 19th and early 20th century, many Hebridean households had a small loom (beairt bheag) with one shuttle. For households who wanted to sell cloth, it was more efficient to replace the small loom with a more mechanised, faster Hattersley, which had two shuttles and a recognisable clackety sound.

Designs

Designs of tweeds and blankets could be very inventive, a Danish Anthropologist Susanne Barding who did fieldwork in Berneray remembers:

‘In Edinburgh I was shown a shawl, … woven in Berneray at the beginning of the 20th century. It featured shades of brown and was woven from a very fine thread. The pattern, I was told, had been copied from the label on a whisky bottle, so inspiration could be drawn from many different places. There were also traditional patterns such as diamond, (sùil), herringbone (cnàimh) and ball and sickle (ball’s corran).’

Dyeing

These blankets lived in low blackhouse light, and latterly in a chest, so the colours are very vibrant despite being over 90 years old. The wool was dyed using natural plants and herbs. Many dyes came from lichens known as crottals.

Although I don’t know exactly what dyes my grandmother used, plants I still see growing in Berneray could produce the following colours:

- Red – “crotal-geal” – white crottle

- Black and grey – “seileastair”, iris root

- Bright blue – billberries, or blueberries

- Bright yellow – sundew

- Green – “duilleag seileisteir” – iris leaves

Weaving now – an interview with Rebecca Hutton

Rebecca Hutton owns Taobh Tuath Tweeds in Northton, Harris. We chatted about how weaving has changed over the years.

I started weaving in 2012 in Scalpay with Sheila Roderick, as part of a training scheme. After two weeks I came home, built my own loom shed and carried on learning. Then I weaved for Donald John MacKay in Luskentyre and learned a lot from him.

It’s important we don’t lose the traditional colours of the tweed. People say they don’t like them because they’re dull, but that’s not true! If you look up close they’re full of bright colours. The colours of the sea can be very dark here, or very bright and I’m inspired by the island.

My loom is a Hattersley mark II. The mark II is a little more industrial than the mark I, with bigger shuttles. If you see someone weaving on a Hattersley, their hands will run all over the tweed looking for breakages or knots. The modern looms are now so sophisticated that they have alarms for when things go wrong, and weavers can read or watch TV.

Hattersley catalogue © SCRAN

Traditionally, tweed was soaked in urine and bashed on a long table to tighten the weave (waulking). Nowadays it’s done at the mill, mechanically while it is washed, so a bit of a cheat! That part’s easy for us now.

I don’t weave for a mill, but it’s interesting that the weaver who wove your grandmother’s blankets did a similar job to the mill weavers now, whose patterns are given to them by the mill. Although they dress their own mills, they have no control over the design, so those weavers are fulfilling the same function, weaving someone else’s design, nearly 100 years apart.

New ways of seeing

After speaking with Rebecca, whose inspiration comes from the landscape, my grandmother’s brightly coloured blankets have more meaning.

She told me she thought they might have been woven on a wooden loom. These looms had four pedals, not two, so it was easier to weave complicated patterns.

I always thought the colours were unusual. Now I see the landscape of the machair, and the colours of its flowers; corn marigolds, buttercups, poppies, and bluebells. Surrounding it is bright blue sea, pale sky and the creamy white of the Berneray sands.

All the blankets in this post were photographed by the very talented Anne Martin, who works as a Photographic Manager within our Heritage Directorate. She can often be found rummaging around the vast collection of exciting historic photographic material within its archives and digitising it for all the world to see.