In April 1558 Walter Mylne, the last man to face the Scottish inquisition, stood accused of heresy in St Andrews Cathedral after being imprisoned in St Andrews Castle.

82-year-old Walter Mylne stood before archbishop John Hamilton, sub-prior John Winram, doctors of theology from the university and other churchmen, boldly denouncing the Catholic mass and defending priests’ right to marry.

This sort of talk was not new to the town. Discussing Protestant views was illegal “unless it be to disprove them, and that by clerks in the schools only.”

St Andrews with its university colleges had clerks aplenty, and discuss they did. Not everyone ‘disproved’ – as the law required – Protestant criticism of the church’s practices and corruption, or their emphasis on the Bible over church tradition and authority. In the last three decades three men had been executed as heretics in St Andrews for sticking to their protestant beliefs. And here was Mylne sticking to his.

Walter Mylne is remembered (as Walter Mill) in St Andrews on the Martyr’s Monument.

The country vicar

As a younger man, Walter Mylne was a monk of Arbroath Abbey and later served as a vicar of Lunan in Angus for twenty years. Reforming ideas from Europe reached him there.

Church authorities led by the powerful cardinal David Beaton, then Archbishop of St Andrews, suspected him of slipping from their doctrine to dangerously heretical, Protestant territory. Beaton executed another Protestant and was himself murdered in 1546.

Mylne left Scotland for the continent and spent a decade somewhere safer – we don’t know exactly where. When he returned with a wife and children in tow, the charges against him were brought up again.

The moderate listener

Meanwhile, in St Andrews John Winram was keeping a cool head. With the cardinal dead and the prior-in-name of the cathedral community still in his teens, it was for the sub-prior to steer the church.

He arranged formal debates at the university to hear the arguments of the remaining protestants and let them explain their stance to the townspeople in weekday sermons. He was calm and gentle, appeared impartial, and guarded his personal beliefs.

But he also started to recruit Augustinians with a mind for reform into the cathedral priory.

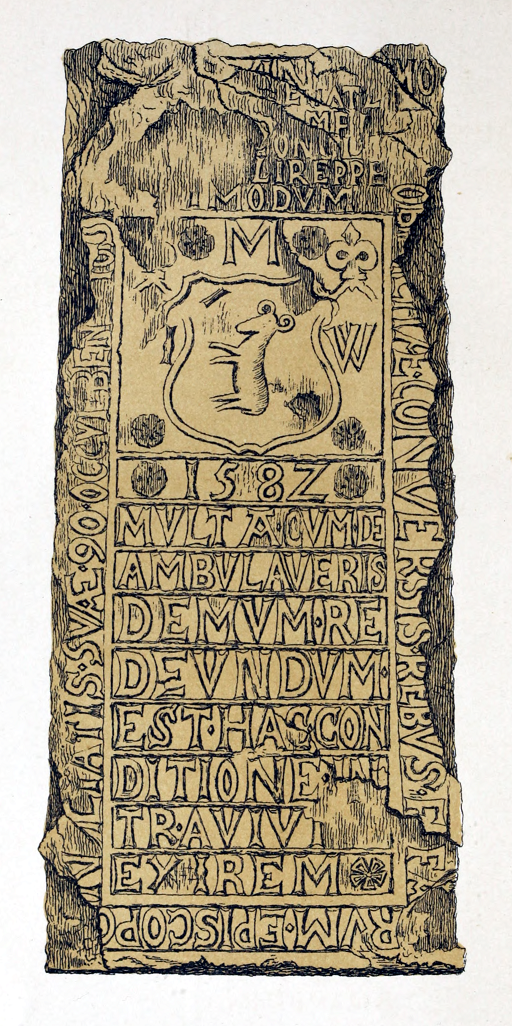

Drawing of John Winram’s tombstone, taken from the Register of the minister, elders and deacons of the Christian congregation of St Andrews (1889) – Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The powerful and the political

When John Hamilton was confirmed as the next archbishop, however, such liberal goings-on were curbed.

Hamilton’s slower reforms concentrated on education of the Catholic clergy. He knew the church expected a man in his position to weed out heresy, whether he liked it or not.

A man in his position was also up to his neck in the politics of the day. At this time, politics and religion were entwined. When the time would come to choose between Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Protestant lords who forced her to abdicate, Hamilton would choose the queen.

One of those Protestant lords would be no other than the prior-in-name from Hamilton’s own cathedral. James Stewart, who was as good as raised by John Winram, was the illegitimate half-brother of Mary.

He would become the Earl of Moray and Scotland’s regent, whose government would declare Hamilton a traitor.

The Hamilton Façade of St Andrews Castle is named after Archbishop John Hamilton, whose heraldic flowers are carved above the castle entrance.

Sticky endings and new beginnings

On that fateful April day, however, James Stewart was in France arranging Mary’s marriage. He did not hear Walter Mylne speak in his trial.

Mylne knew that his words would condemn him to burn at the stake as a heretic.

“Do witht me as ze pleise zour selffis at this tyme, I man tholl zour iudgement bot better it war to zour lordschipis to helpe and gif me sum thing to my wyffe and tuo bairnes, quho ar lyk to tyne for faltt; as ffor my death I cure not.”

Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie quoting Walter Mylne in The Historie and Chronicles of Scotland

Mylne was indeed convicted, but the court’s decision was not popular. Merchants of St Andrews refused to sell wood, rope or tar for the pyre, and the town provost refused to act as the judge to carry out the death sentence of a frail old man.

Even Hamilton himself was said to admit he had “no will that he (Mylne) sould die at this time.” Days after the trial one the archbishop’s servants, “more ignorant and cruel than the rest”, led the execution on the north side of the Cathedral.

Mylne’s wife, whose name is unknown, was granted a pension. Townspeople raised a cairn in his memory and, when church authorities scattered the stones, they stacked them again.

What happened next?

A year after Mylne’s execution, James Stewart gathered men to turn St Andrews into a protestant town. The year after that, the parliament chose Protestantism for all of Scotland, but many people continued to practice Catholicism.

Later, Stewart was shot and killed on the street in Linlithgow by Hamilton’s nephew from a house he owned. Hamilton was hanged in Stirling for his treasonous support of the queen.

The industrious John Winram moved from the helm of his Catholic brethren to organising the new kirk. He oversaw the reorganisation of parishes staffed by reformers he had stashed away in his priory, and worked to uphold standards and discipline.

19th century replica of the 16th century memorial to James Stewart, who was buried in St Giles in Edinburgh. Image by CPClegg.

Keepers of the stories

We can read Mylne’s words, or at least words given to him by chroniclers who praise him.

But no-one knows what Pavel Kravař said before he was burned for his faith in St Andrews 125 years earlier. Kravař’s time was against him, no chronicler was on his side, and the writings of heretics were destroyed to leave no trace.

In time, the once magnificent St Andrews Cathedral where Walter Mylne defended himself was almost destroyed to leave no trace either.

The ruins and museum collection are now in our care and, if you visit us when we re-open on 30 April 2021, we will happily share the stories of everyone; catholic, heretic and reformer alike.