Stanley Mills, the 18th century cotton mill on the banks of the River Tay, always had a predominantly female workforce.

Our Learning and Inclusion Team have been able to involve a number of former Stanley Mills workers in various Learning Programme projects and activities, including Kate Gairns, Margaret Reiche and Nell Hannah.

The stories of these women, who worked at the Mills during World War Two, bring to life the social history of this industrial site.

Working Life on the Homefront: Making the products

During the war, Stanley Mills produced army webbing (woven cotton which was turned into military belts, packs and pouches). Narrow cotton tapes, used in cigarette factories, were already a key product.

The tapes were made by women in the Tape Weaving department (also known as the Band Room). Jobs in the Band Room were much sought after because they were cleaner than working in the main mill.

The women were paid per tape and were expected to make between 32 and 36 each day, according to former supervisor Kate Gairns. Kate started work at the Mills in 1936, aged 14, and recalled:

I thocht to masel, “Oh, I’ll never stick this”. I came home at lunchtime and said to my grandmother, “No, I don’t think I’ll like it”.

My grandmother replied “Never mind Kate, just go back. I think ye’ll find ye’ll be alright in the afternoon.”

She was still there 41 years later!

Kate Gairns in 1940 with her friend Hilda Crawford (© Kate Gairns / By kind permission of www.stanleyperthshire.co.uk)

Margaret Reiche remembers the camaraderie between the women, going to the dancing at night and sharing stories the next morning.

An advantage of working in the Band Room during the war was the opportunity to catch the attention of the British soldiers who were camped behind the mills. Many an excuse was made to go to the rest room to get a closer look!

The North Range at Stanley Mills where the Tape Weaving Department was based

Everyday life on the home front: blackouts, bombs and rationing

Wartime blackouts applied to the Mill and shields were used to block out any light from the many windows. Streetlights on Mill Brae were also turned off so the women would make their way home in the dark arm in arm. Kate recalled

It was an awffy job getting yer way home with just a wee torch”.

The workers carried gas masks and had regular air raid drills. The women may have been forgiven for thinking the safety precautions were a bit unnecessary, but they were for good reason. This became apparent during November 1940 and April 1941 when two German bombs landed near Stanley. Allegedly, the only thing injured was a rabbit!

Scottish women reach the front of a rations queue in 1945 (© Newsquest (Herald & Times). Licensed via Scran)

Rationing affected day to day life for workers, just as it did the wider population. Nell Hannah would save up her sweetie coupons and then spend them once a month in one of the two sweet shops in Stanley village.

When Nell was expecting her first baby, she was at the grocer’s when a delivery of oranges had been made. As pregnant women were given priority for oranges at the time, the grocer asked Nell to open her bag and tipped in 15 of them!

Supporting the war effort: Spitfire funds and comfort boxes

In 1940, Spitfire funds took off across the country. These encouraged local communities to raise money to ‘buy’ a Spitfire (at a theoretical £5000!).

Nell Hannah helped organise a ‘basket tea’ for the Spitfire Fund in St Columba’s Church Hall in Stanley. A keen performer, Nell wrote and performed the entertainment for the evening. Margaret Reiche played banjo in a concert band. She would put on shows at venues in local villages for wartime fundraisers.

Margaret (far right) playing in the 7 Star Band (© Margaret Reiche)

Another initiative was Comfort Funds which provided luxuries or ‘comfort’ items to soldiers. The Funds relied on fundraising and donations to supply items such as socks, cigarettes and soap.

Stanley Mills took 3p a week from millworkers’ wages for comforts for the troops. Requests could be made for a comfort box to be sent to a relative or someone they knew in active service. Nell Hannah nominated a lad she’d dated called Harry, who had joined the merchant navy.

This comfort box led to Nell’s marriage. When Harry was home on leave, he came to thank Nell and asked how she would feel about ‘getting hitched’. Nell said ‘yes’ and it was all go to make the arrangements before his leave was up…

Weddings in Wartime: Getting hitched

On her wedding day, Nell wore a utility outfit and a pillbox hat with a long feather. Her 18 guests enjoyed a wedding meal of mince and tatties followed by trifle and clootie dumpling. The cost came in at 12 shillings and sixpence.

As was tradition in many factories, workers celebrated a colleague’s upcoming wedding by dressing them up and having a bit of fun.

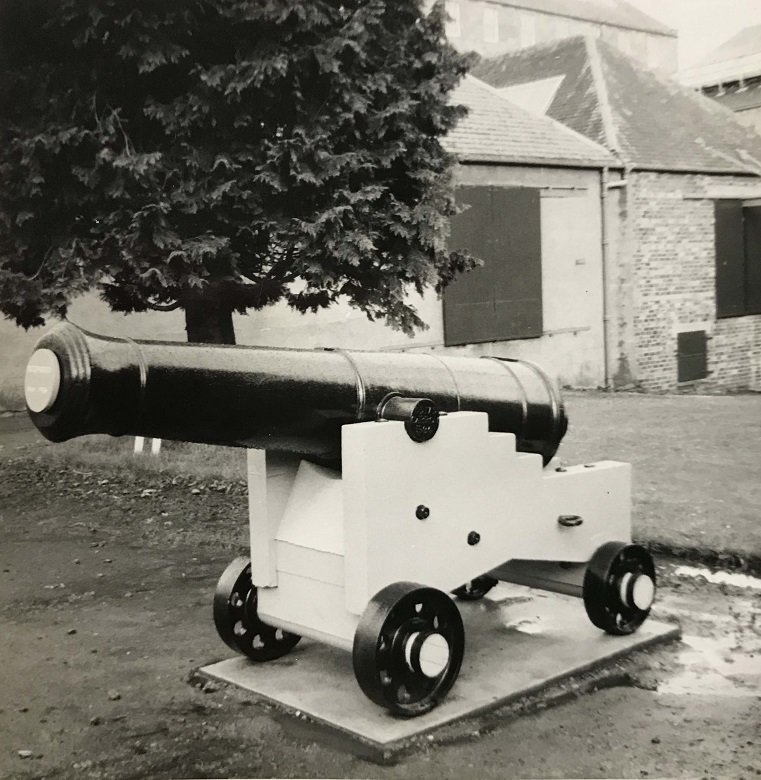

Both Nell and Kate were put in a bogey (a basket on wheels used to move bobbins) and given a big hat, an L plate and a chamber pot of salt with a baby doll in it. Nell was pushed at great speed round the floors of the mill, while Kate was pushed down Mill Brae. She was tied to the Mill cannon when she reached the bottom!

The cannon that previously sat in Mill Square and was at the centre of celebrations prior to Kate’s wedding (© HES Collections)

The pre-wedding shenanigans continued at factories and mills beyond the 1940s. The photograph below shows Jean Brodie leaving Luncarty works having been dressed by her workmates prior to her wedding in 1959.

(© Mary Rennie / By kind permission of www.stanleyperthshire.co.uk)

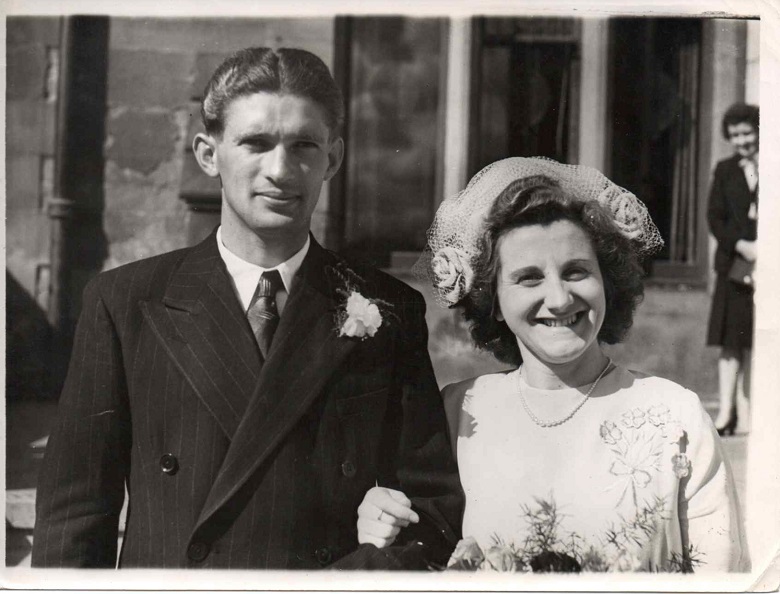

Margaret married a former Prisoner of War who worked on a farm in Perthshire. They met after the war at a concert in Perth City Hall and married in 1949. It’s hard to imagine Margaret announcing the news that she was marrying a German so soon after the war, but it may have reflected village attitudes towards foreign troops who ended up living and working in many rural areas.

Margaret and Henri’s wedding day (© Margaret Reiche)

Foreign bodies: Polish picnics and Italian chocolate!

After Polish troops took over the defence of Fife, Perth and Angus in October 1940, women millworkers would have encountered soldiers in social contexts – ‘at the dancing’.

Polish soldiers were in the audience at a Women’s Rural event that Nell was involved in. A captain asked Nell to repeat the performances for his troops at the Campsie Linn beach close to Stanley Mills. The event had a picnic, a Polish orchestra playing Strauss waltzes, a choir and singing.

Campsie Linn (© Gareth Edwards)

In 1942, Italian Prisoners of War were billeted next door to Nell’s house in the village. Imagine her surprise when, one day, having left her daughter in her pram outside her front door, she returned to find Italian soldiers surrounding the baby, feeding her pieces of chocolate, saying ‘bambino, bambino’.

Nell had some sympathy for the men, many of whom would have been missing their own families.

A view of Stanley similar to that which the Italian POWs would have encountered (By kind permission of www.stanleyperthshire.co.uk)

Wartime yarns: Sharing stories of Stanley Mills

It was hard work at the mills and wartime life was at times difficult. But the women had positive memories that reflected the camaraderie often found in factories.

The children and adults lucky enough to meet the women as part of the learning programmes at Stanley Mills had a richer experience because of it. Today, these stories form a legacy for future learners.

Below is a felt banner which hangs in the Education Room at Stanley Mills. It depicts Nell’s concert for the Polish troops at Campsie Linn.

© Fiona Davidson/HES

There’s plenty more industrial heritage on the blog! For instance, you can step inside the Clydebank Singer sewing machine factory. After that, head underground to discover the unique tunnel built for one of Scotland’s pioneering railways.