The Isle of Luing is a small gem nestled among the lochs and mountains of Argyll, providing nourishing fodder to a thoroughbred herd of cattle and a stunning home to almost 180 people.

Luing is famous for the part it played in Scotland’s slate industry. Everywhere you go there are great quarry faces, workers’ cottages and huge grey piles of fragmented waste.

But earlier features survive. Some of the most fantastic are the Iron Age duns. For roughly 2,000 years these sites have looked out over routes that linked so much of the western seaboard in the past.

Community history on Luing

Recently, we were privileged to survey the island with the support of the Luing History Group, using community-funded 3D data. The group gives a focus for those interested in history and archaeology: undertaking walks and talks, as well as hosting exhibitions at the Atlantic Islands Centre in Cullipool.

The enthusiasm and hard work of community archaeologists from Luing and the Association of Certified Field Archaeologists have already resulted in the discovery of hundreds of new sites. Our survey allowed us to record the sites and make information about them available to everyone via Canmore.

Prehistoric remains in the Luing hills

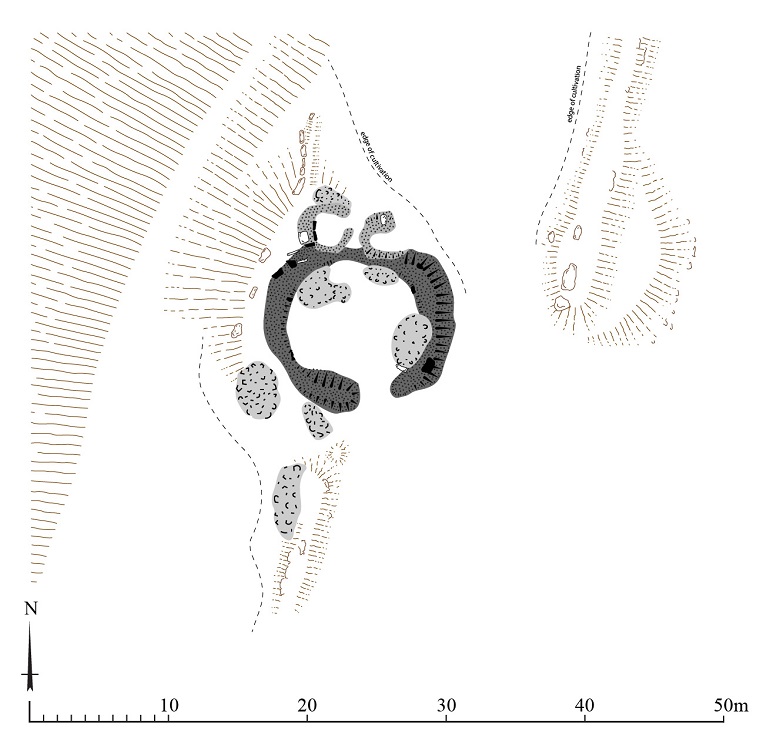

One of the great discoveries of the project was the well-preserved wall footings of a prehistoric round house. This was the typical dwelling for most Bronze and Iron Age people. It was built with stone, earth and turf walls and topped with a thatched roof.

This one survives tucked among the rocky slopes of one of Luing’s low hills. The plan of its ancient wall can be teased out from the remains of later huts and cleared stones that have been dumped upon it.

Two small huts built by shepherds in the post-medieval period overlie the northern arc of the roundhouse. The stones were added later by farmers clearing the nearby fields.

A plan of the newly-discovered round house created during the Luing survey

Chopping and changing

The 3D data and survey work are also rich sources of information about later centuries.

After Luing was split up into a series of farms, there was a great deal of chopping and changing during the 18th and 19th centuries, as farmers and landowners reacted to fluctuating fortunes.

Fragments of these landscapes survive as buildings, tumbled walls and fields that once supported crops of oats and potatoes. Like much of the old farmland in the Highlands and Islands, most of Luing is today used for grazing cattle. They graze over the walls that remain. You can pick them out in the aerial image below.

An expert eye

All in all, the project recorded 294 new sites on Luing, as well as the Isle of Torsa and the southern tip of Seil. Mary Braithwaite, from the Luing History Group told us that HES

brought an expert eye to Luing’s archaeology. It helped us better understand sites and, most importantly, has made them publicly accessible through Canmore.”

Mary also noting that the survey resulted in some excellent photos, which can now be viewed online, along with more information about our Luing project.