Have you seen our spooky video recounting the tale of the Earl of Huntly’s death? Follow us to Huntly Castle!

Our Halloween feature of the the noble ruin of Huntly Castle is based on a contemporary account, written by Richard Bannatyne in his Memorials of Transactions in Scotland, 1569-1573. Whether you believe in the ghostly goings-on or not, a lot can be learned from Bannatyne’s work.

You can read the account in old Scots on Internet Archive. I’ve also provided a brief summary at the end of this blog.

Now let’s take a look at the truth behind this ghostly tale!

Was Huntly Castle the scene of ghostly goings-on after Earl Huntly’s death?

Unpicking the evidence

When working with historical sources, there are certain questions we should always ask:

- who wrote it and why?

- is the author biased?

- what does it tell us – and is it accurate?

- when was it written?

- and, where did the author get their information from?

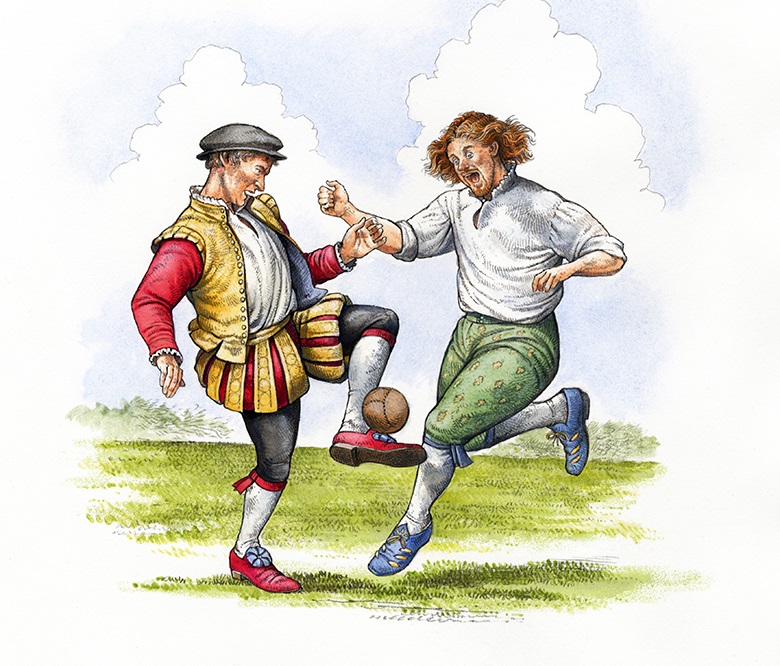

Written in Scots, the account tells of how George Gordon, the 5th Earl of Huntly, collapsed while playing football one October in 1576. We get a rather gruesome description of the Earl’s suffering and final throes – vomiting black bile and foaming at the mouth. His death comes shortly after.

What follows is a strange sequence of events. Members of the Earl’s friends and household are struck down with a similar unexplained illness. Each one suffers deathly cold chills and hours of shivering and terror before miraculously returning to good health. Were these men afflicted by some curse or evil spirits? Or was it some unknown illness? And were there really bangs, moans and voices coming from the Earl’s empty chamber after his death?

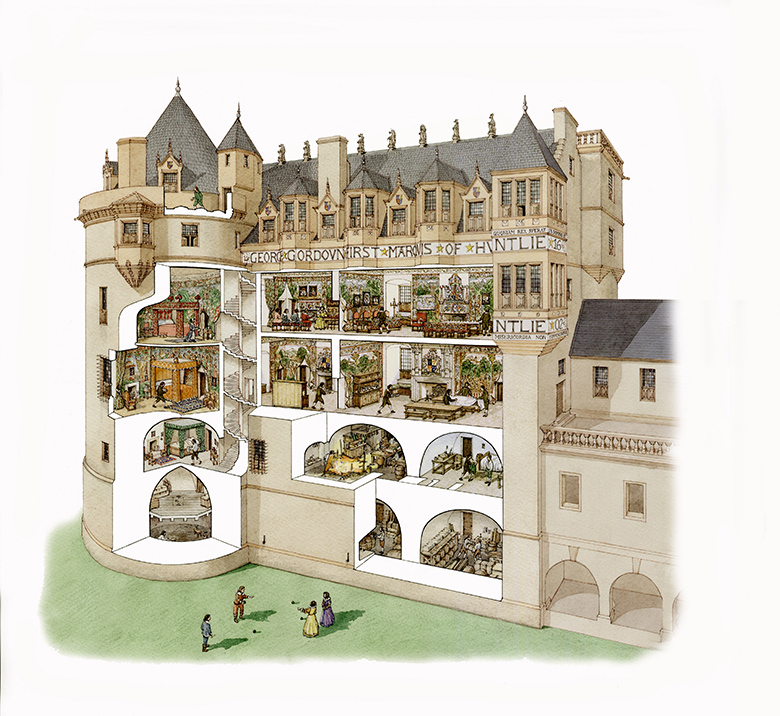

Bannatyne’s detailed descriptions not only tells us about these events, but also the castle interior, the Earl’s apartments and how they were used. Indeed, this one source has helped to inform subsequent records of the castle and our own modern interpretation.

But can we trust this source?

Possibly the world’s oldest football was found in Stirling Palace, dating to the 1540s, and there are records of the game being played at Carlisle Castle and Edzell Castle around this time too.

Who was Bannatyne? What do we know about his work?

The original manuscript survives in the National Archives. It was transcribed and published by Robert Pitcairn, an antiquarian, several centuries later in 1836. Did he accurately transcribe the document? Did he have his own agenda in publishing Bannatyne’s work – or did he add any embellishments? All careful considerations to make before believing this tale!

We also need to think about Bannatyne himself and any biases he might have had. What little information we do know about Bannatyne comes from Pitcairn’s research. He was a clergyman and secretary under John Knox, so we can assume he was a devout Protestant and a well-educated man. But perhaps he was not the biggest fan of the Gordon family, who were notoriously lavish and outwardly Catholic?

Bannatyne was a contemporary of the Earl. He was alive at the same time and wrote about events that happened during his lifetime. But his source of information for these events is somewhat questionable. It seems he spoke to someone, who had heard from someone else who was there! As well as considering Bannatyne’s religious, even moral, biases we need to be wary of the accuracy of his account too.

Strange thingis…

It would seem to be quite an elaborate account. What do we make of the ‘diverse strange thingis’ that happened after Gordon’s death? We now believe he suffered a stroke. Perhaps not unsurprisingly given the strenuous, even violent nature, of 16th century football matches and the undoubtedly indulgent lifestyle of the Earl!

Yet to those by his side at the time, it would have seemed like a sudden and completely unexplained event. This may have struck fear into these men. With little scientific medical knowledge, and the superstitions prevalent in early modern society, perhaps the Earl’s death would have been seen as supernatural.

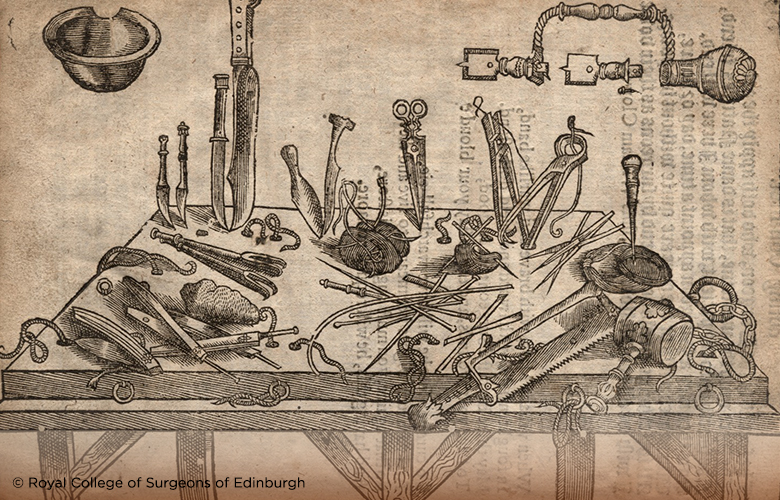

A surgeon travelled from Aberdeen to determine the cause of the Earl’s death and prepare his body for burial. He may have used tools such as these for embalming.

An illustration of 16th century surgical and dissection tool from William Clowes ‘Observations for all those Burned with the Flame of Gunpowder”.

A tall tale or a telling insight?

While we must question the factual accuracy of the cold shivers and strange noises experienced by Gordon’s household, there is a great deal that we can learn from this source. It give us plenty of information about noble life, residences, leisure activities and even beliefs, culture and the intellectual world in the 16th century.

It is especially important for telling us about the interiors of Huntly Castle. The account tells us what the castle was like before the 1st Marquis’ renovations in the early 1600s.

From the description of the rooms, and the route the Earl’s attendants took going to and from his chamber, we learn that the south range had separate suites for the Earl and Countess. The Earl’s chamber seems to have been separate from the hall, with private quarters at one end. The Countess almost certainly had a mirrored series of rooms above. A sure sign that they were a leading noble family and keeping up with the latest architectural fashions and social etiquette. Intriguingly there is also reference to a chapel within the castle. Nothing survives of this chapel today, but we would certainly expect a private place of worship for the family.

The third floor in this illustration shows the Earl’s suites. The Countess’ suite is above.

A reckoning from God?

Towards the end of the account, Bannatyne reveals why these supernatural events may have taken place. The Gordon family were staunch Catholics and the Earl had long been loyal to Mary Queen of Scots – and at odds with several of the Regents that ruled in James VI’s minority. He was one of several powerful men suspected of being involved in the murder of Mary Queen of Scots’ second husband Darnley, and the death of Regent Lennox.

Was his untimely death an act of God? Is this a moral treatise, warning others not to follow in the Earl’s footsteps? Perhaps the suffering of his allies was perceived as a curse, or deed of the devil.

Bannatyne’s closing words strongly suggest the Earl got what was coming to him, after his traitorous actions. This casts doubt upon the source’s reliability but tells us something fascinating about the moral and intellectual world at the time that Bannatyne was writing.

A note on filming at Huntly Castle

It might interest you to know that our intrepid film maker and reenactor filmed on location at Huntly Castle on 19 October, which some accounts record as the same date that the Earl died in 1576!

The current pandemic meant we couldn’t film in some of the exact locations mentioned in the account, but excitingly most of these rooms still exist at the castle alongside the exquisite carvings added by his son, the 1st Marquis of Huntly.

If you’ve not been put off visiting Huntly Castle by all these strange goings on, make sure you book your tickets to visit in advance.

A summary of Bannatyne’s account

You can read the historic account online, but it can be hard to follow if you’re not familiar with old Scots. Here’s a brief outline of the key events of the story.

The Earl of Huntly died suddenly while playing football. This was unexpected as he was in good health.

He fell while playing and had to be carried by his companions back to the castle. The Earl fell again upon entering the castle grounds.

He was laid to rest in his bed chamber where his condition worsened. He vomited black blood or bile, and foamed at the mouth.

A man called Adam Gordon immediately set about making arrangements. He moved the Earl’s body to the high chamber and made an inventory of his belongings. He took money out for himself for his ‘expenses’, placed burning candles in the room where the Earl lay and locked all the rooms and cupboards again.

Adam entrusted the keys to John Hamilton, a trusted noble.

Why does it feel so cold?

Early on Sunday morning, in the laich (lower) chamber a group of men (presumably part of Earl’s household or close companions) gathered. They reflect on their own mortality.

A man from the west coast (Assynt) stood with his back to the fire, lamenting his own difficulties. Suddenly he fell flat, face down as if dead. He was picked up and taken to the window for air. Still warm, but unconscious, they carried him to a chamber and laid him in bed. After 30 mins rest he woke, but was rubbing his hands and body and shouting of the cold.

On the Tuesday, John Hamilton went up to the gallery in the palace to fetch some spices, along with James Spittel and a servant. John opened up the store but was immediately struck with illness and cried out that he was cold, then collapsed. The others carried him to get fresh air. He said he needed to rest in bed. James Spittel took him downstairs. James remembered he’d left a coffer open so they both returned to put things right.

Upstairs, they found the unnamed servant keeled over the coffers, presumed dead. John exclaims that evil is afoot! James gathers other men and they carry the servant up and down the stairs to revive him. Eventually he is put to rest in bed and, like the first man, he recovers quickly but complains loudly of the cold.

All of these men seem to have experienced the same symptoms as the Earl, other than foaming at the mouth and nose, and the black vomit. Yet each of them recovered.

A surgeon from Aberdeen comes to prepare the Earl’s body. Once prepared, his body is taken to the chapel where it is left until burial. The chamber is locked up.

Strange noises are heard

On the Wednesday, Patrick Gordon (the Earl’s brother) was sitting near to the door of the Earl’s chamber when he heard loud noises within – someone speaking, groaning and rumbling noises. Nineteen or 20 other men were with Patrick at the time. John confirms no one was in the chamber or could have gotten in there. Patrick demands John open the door but he refuses – so Patrick goes in first, with John tentatively following.

Inside the chamber Patrick hears the same noises again, but can’t see anything – though the light was fading fast. He quickly leaves, returning to the hall – terrified. He explains to those in the hall what happened, all are too scared to cross the threshold into the Earl’s room.

Eventually they get candles and go to explore the chamber, but nothing is there. But while in the doorway the noises start again and the candles flicker. The implication is that there is something in the room and that whatever spirits are inside do not want anyone to cross over the threshold. The air is close. Some claim that is the Earl ‘risen again’ – Patrick demands that no such rumours are spread.

Musing on the tale

Bannatyne claims that around the time of the Earl’s death, this tale/rumour was commonly known and spoken of, among the rich and poor alike.

Adam Gordon returns to look after the funeral of the Earl. Upon his return, the story was changed: the Earl died peacefully and his funeral arrangements and treatment after death all went smoothly.

The final paragraphs could be referring to the Earl’s possible involvement in the killing of Regent Lennox. They may also allude to the Earl’s Catholicism and support of Mary Queen of Scots. Bannatyne seems to be reflecting on whether the Earl was an upright moral character or a traitor to James VI.