In Scotland we often think of ourselves as a welcoming country. But in the early 20th century, when Edinburgh venues introduced a ‘colour bar’, many residents and visitors to the city found themselves treated as second class citizens.

An unfounded hope?

In January 1921, 17-year-old Diwan Pitamber Nath made the 5,000 mile journey from Punjab in British India to Liverpool. He wanted to become a doctor. Perhaps he was inspired by Queen Victoria’s promise to the Indian people in 1858 that “…all shall alike enjoy the equal and impartial protection of the Law… whatever Race or Creed”.

Nath set his sights on Scotland where, even as early as 1920, it wasn’t unusual to see students of colour from the British colonies. Edinburgh was home to the first South Asian student association in Britain and Nath would have been an active member in the Edinburgh Indian Association (EIA).

Shortly before Nath embarked on his journey to Edinburgh, the YMCA even opened a dedicated hostel for Indian students at No. 5 Grosvenor Crescent. He may have stayed there when he first arrived in the city.

An image of 5 and 6 Grosvenor Crescent from the HES Archives. (Dick Peddie and McKay Collection)

But as Nath reached his final year of study, there was an unwelcoming shift in the city that had become his home away from home.

The Edinburgh Indian Association and the Indian Students’ Union began to receive letters from local venues. One, later published in the Guardian on 1 June 1927, read:

“I should like you to inform all members of the Union who use the above restaurant, on and after Saturday 23rd inst. admittance will be refused…

I may add that this is not directed against the Indian community only, but includes all coloured patrons.”

Edinburgh had introduced a ‘colour bar’.

The 1927 Edinburgh Colour Bar

Dance halls offered most of the entertainment and opportunities to socialise in the early 20th century. Venues like the Palais de Danse in Edinburgh hosted up to 900 dancers on a good night.

However, based on the colour of their skin, Edinburgh’s population of Indians, Africans, Caribbean and Chinese residents, many of them students like Nath, were now unable to attend. They found themselves being treated as second class citizens in the Scottish city they called home.

The Riviera Novelty Dance Orchestra played at the opening of the Palais de Danse in Fountainbridge, Edinburgh. Image © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

By early 1927 most dance halls, along with some cafes, restaurants and boarding houses, placed restrictions on people of colour. Managers unashamedly cited their reasoning as being to appease other – white – patrons, who objected to sharing a space with people of other races.

As the segregationist policy took hold across the city, the Assembly Rooms and Music Hall on Edinburgh’s George Street was the scene of “protest meetings”. Records are unclear whether the dance hall itself operated a colour bar.

81 years prior, African American freedom fighter Frederick Douglass had been welcomed there to speak against slavery to an audience of 2,000 listeners. Paradoxically, if they did operate a bar and had he arrived in the 1920s, Douglass may not have even been allowed to enter the building.

The Music Hall was one of the most popular venues for dancing in Edinburgh through the 20th century.

The Edinburgh Indian Association

With growing support for independence in India and a coordinated community body in the EIA, Edinburgh’s Indian residents became bolder in their fight against this blatant discrimination. Some particularly vocal figures were Dr S A Rahman, Brajanath D Chowdhury and Nath himself.

The EIA refused to take part in the Empire Day pageant celebrations of 1927. Dr Rahman relayed the collective feelings of Edinburgh’s Indian population in a telegram to the King’s Private Sectary.

On 21 May, he spoke to The Scotsman of the “…humiliation and the spirit of racial hatred” that left the Indian population feeling unable to join the celebrations due to an “…[incompatibility] with our sense of self-respect…”.

In the Westminster Gazette, Indians described feeling as though they were treated as “social lepers” in the Scottish city.

In 1875, Indian students formed the Edinburgh Indian Association, housed at 11 George Square. It was one of the first Edinburgh University Societies to allow women into its membership.

Image from the HES Archives (List C Survey).

International attention

In retaliation to the colour bar Nath, who had gone dancing in the halls he was now banned from, told The Scotsman on 21 May 1927:

“These students … would naturally tell their countrymen what they had undergone. The bar … would become known to, and would be resented by the millions in India…”

Indeed, in seeking international support, the EIA sent reports of the Edinburgh colour bar to every leading newspaper in India. The resulting headlines added fuel to the flames of India’s growing independence movement.

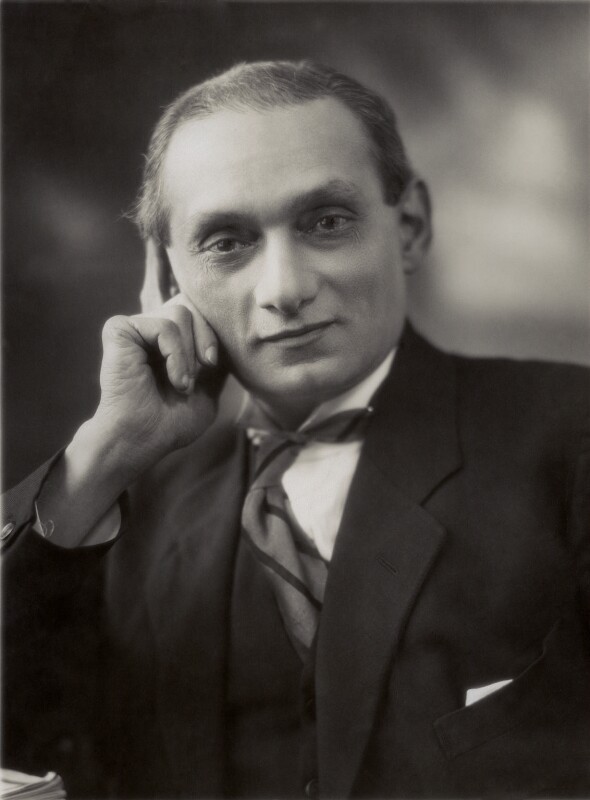

Shapurji Saklatvala, Britain’s third MP of Indian birth, raised the issue in the House of Commons and asked for support to “put an end to an extremely obnoxious practice”. Image © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Aware of the growing pressure, the issue was taken to parliament by two MPs, George Lansbury and Shapurji Saklatvala. Unfortunately, while many politicians disagreed with the colour bar, it was decided it was a private matter and not something ministers could get involved with.

Colour bar condemned

In May 1927, the General Assembly of the United Free Church and the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland discussed the colour bar. They condemned it openly, expressing sympathies over the bitterness it had caused.

The colour bar was discussed at the supreme court of the Church of Scotland, most likely held in the Assembly Hall at the New College on the Mound in Edinburgh.

Providing a glimmer of hope, on 3 June 1927, The Scotsman reported that the Magistrates and the Council passed a unanimous motion disapproving of the colour bar. But, though now widely condemned, lifting the policy was not legally enforced. Venues continued to deny entry or services to people of colour.

To keep up pressure, on 10 June, the EIA in its leading role with the Anti-Colour Ban Sub-committee arranged a protest meeting at the Music Hall.

The Music Hall, within the Assembly Rooms, was the location for “protest meetings” in 1927.

They invited Frederick Alexander Macquisten, a lawyer and MP for Argyllshire, to attend. Macquisten responded with fuel for the fire, encouraging people in India to reciprocate. He said:

“In my opinion, you should be very grateful to these proprietors of the dance halls for what they have done. I am sure that all Indian fathers and mothers will be only too glad to have their sons excluded from dance halls, places where they are liable to make undesirable acquaintances, and to waste the time which they ought to be spending upon their studies which their parents make great sacrifices to enable them to pursue.”

The meeting went ahead and by July the Dundee Courier had reported that “a satisfactory arrangement has been arrived at, under which coloured men are to be allowed to attend under certain conditions”.

A statement in numbers

Despite this progress, newspaper headlines a few years later reveal that some cafes and dance halls did not agree to lift the bar. Others made the terms of entry so restrictive it was as though the bar was still in full force. But by the 1930s, patience towards the segregationist policy was very limited.

On Tuesday 28 April 1931, an Indian and an African student visited a cafe in Edinburgh and were refused entry without explanation. This act (reported in the Guardian), lead to the unfolding of an anti-racist stance by customers, one of whom “urged all fair-minded people in the cafe to leave as a protest against the ban.” A large number of those present walked out in solidarity with the students of colour.

Incensed, the Students’ Representative Council of Edinburgh University sparked an investigation and asked for an apology. When none was forthcoming, at the end of May 1931, they declared a boycott by all students of “the Cafeteria and the Strand Café”.

The Strand Café which operated a colour bar seems to have started life as the Albert Hall, then the West End Theatre and later the West End Café , at 22 Shandwick Place. Part of the HES Archives (Public Monuments and Sculpture Association Collection).

Several newspapers published statements by management from other cafes, which included a range of conditions applicable to the permitted entry of people of colour. These were essentially excuses and loopholes that enabled a continuation of their racist practices.

Barring a Black bishop

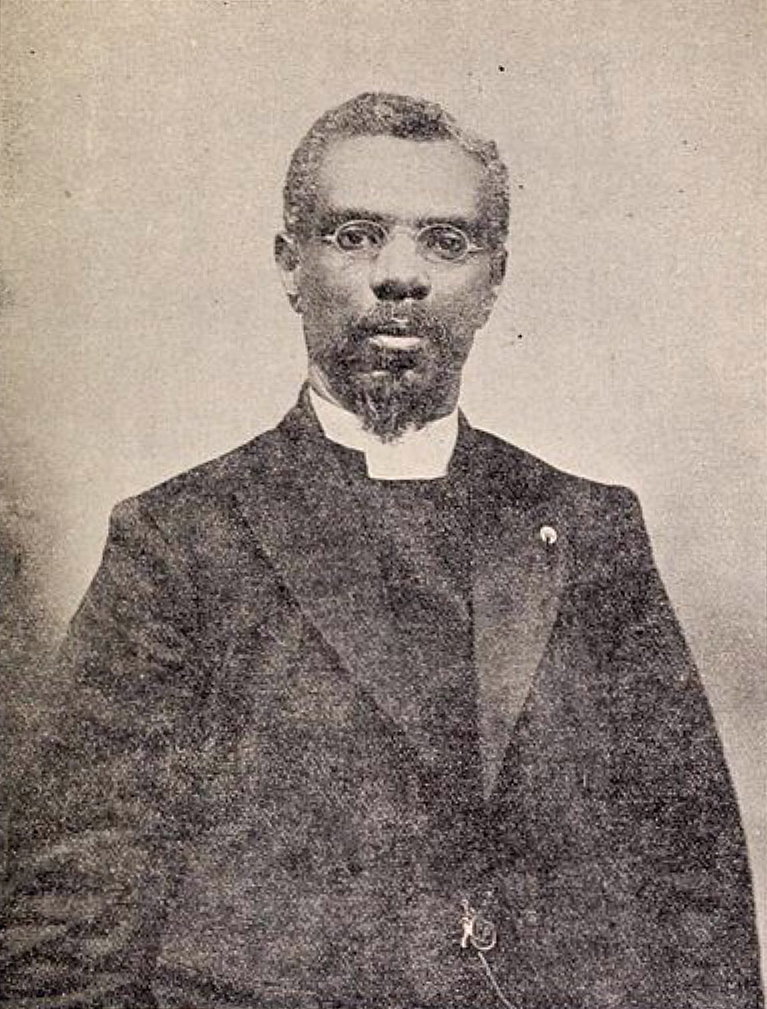

In August 1937, African American Bishop William Henry Heard travelled 3,000 miles with his niece to attend a conference. Heard had been enslaved until the age of 15, before being liberated in the American Civil War. He was a vocal advocate of civil rights and a clergyman of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

© Heard, William H. (William Henry), 1850-1937, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

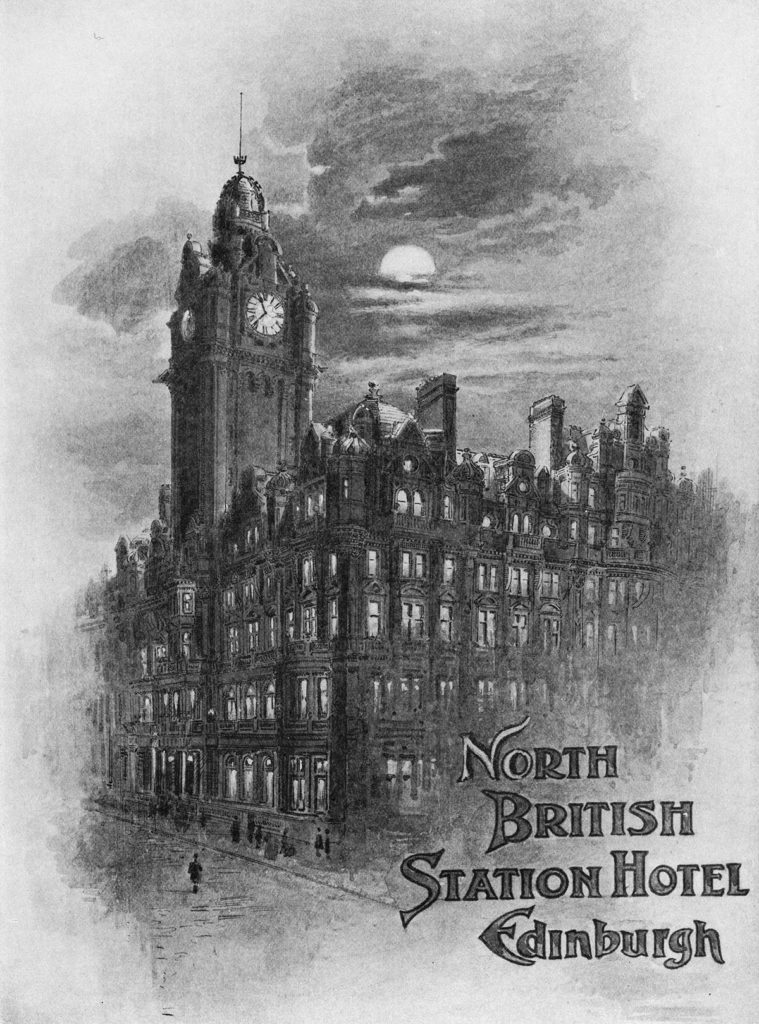

On arrival at the North British Railway Station Hotel in Edinburgh, they were denied entry. That the pair experienced the same racial exclusion Nath had suggests that despite the supporters and solidarity, little had really changed in those 10 years.

After four hours of searching, and offers of hospitality from the Archbishop of York, Bishop Heard and his niece secured a room at a smaller hotel in the West End of Edinburgh.

Part of the HES Archives, a souvenir of the opening of the North British Station Hotel, Edinburgh.

While many hotel managers approached by the press at the time denied the existence of a colour bar, they pointed to the “tremendous antipathy” of their other American tourists towards Black people.

Bishop Heard later received letters from Scottish residents. Embarrassed by his treatment, some even offered to welcome him to their homes if he ever returned. He also received an apology from Sir John Simon, Chancellor of the Exchequer.

End of the Edinburgh colour bars

Reports of discriminatory practices in Edinburgh continue through to the 1950s. It wasn’t made illegal to refuse service on the basis of race until 1965, following the introduction of the Race Relations Act. We know, of course, that this didn’t end discrimination. But what happened to the students who campaigned in the early 20th century?

Diwan Pitamber Nath passed his medical exams. He served as a Lieut. Colonel in the Indian Medical Service in the Second World War. In later life, he worked for the World Health Organisation. He passed away in Edinburgh and was taken back to his family in New Delhi.

Brajanath D Chowdhury, another EIA member who spoke out against the colour bar, married a local woman – Mary Black McDowall. He may have even met her one night in a dance hall.

Today, there are more than 55,000 people of Asian origin living in Scotland. There are also more than 4,000 Indian international students currently studying here. They make up a small but significant 1% of the total population.

Are you related to any of the people we’ve mentioned here? Do you have any images, memories or stories to share? You can email to let us know.

Thanks and acknowledgements to UncoverEd on their research into the Edinburgh colour bar, and to Bryony Donnelly for support on the original source material.