Many of Scotland’s historic places are linked to The Queen. You’re probably aware of royal residences, like the Palace of Holyrood House and Balmoral Castle. You may have stepped aboard the Royal Yacht Britannia at its mooring in Leith.

Several other significant Scottish structures were officially opened by the Queen over the course of her 70-year reign. We’ve delved into the Historic Environment Scotland archives to take a closer look at some of them.

National Library of Scotland: A seat of learning

The National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh was officially opened by the Queen on 4 July 1956.

The Queen opens the National Library of Scotland (© The Scotsman, licensed via Scran)

The striking classical modern building, designed by leading interwar architect Reginald Fairlie, is Scotland’s largest library. Construction began in 1937, but was halted by WWII. The enormous steel frame stood silently on George IV Bridge until work could resume.

When complete, the library was nine storeys high, with two storeys on George IV Bridge, and the remaining seven below the bridge on the Cowgate.

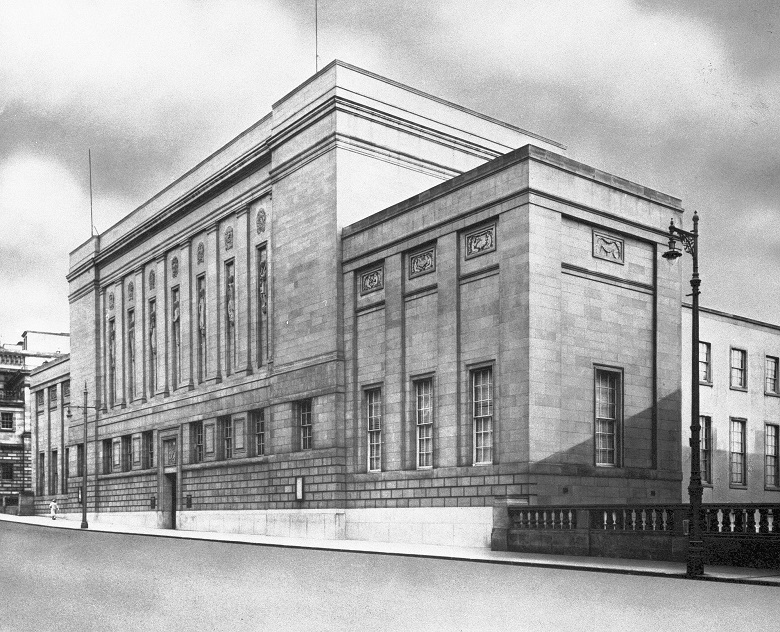

The National Library of Scotland site as it appeared in August 1950 (© HES, Tom and Sybil Gray Collection)

The seven large stone figures which dominate the front of the library are by renowned sculptor Hew Lorimer, son of Scottish architect Sir Robert Lorimer. They symbolise the arts of civilisation: Medicine, Science, History, The Poetic Muse, Justice, Theology and Music.

Inside, you’ll find an impressive main staircase dominated by a stained glass window which includes emblems of the Thistle and Scottish Crown. The public rooms are each fitted with a different kind of wood. The entrance hall is teak, while the catalogue hall is mahogany, the reading room walnut and the former special collections rooms pine.

The National Library in 1955 (image via Canmore)

The main staircase in the National Library (image via Canmore)

Ben Crauchan: Power in the mountains

Cruachan Dam high above Loch Awe

Of the many buildings opened by the Queen, the Ben Cruachan hydro electric scheme must be one of the more unique.

Constructed between 1959 and 1964, the pioneering power station utilises a huge dam and a turbine hall built inside Ben Cruachan to move water a height of 396 metres between Loch Awe and Cruachan Reservoir. It can move from a standstill to full output in under two minutes, and is capable of operating non-stop for 22 hours.

The vast turbine hall is 36 metres high and 90 metres long, and is accessed via a tunnel one kilometre in length. The Turbine Hall is listed at Category A and the Dam is listed at Category B.

The Queen meets North Scotland Hydro Electric Board staff at the official opening of Cruachan Power Station

The Queen is introduced to Cruachan Dam in 1965 (© The Scotsman, licensed via Scran)

Hutcheson C: “Ships in full sail”

From hydro electricity to high rise housing, Hutchesontown C was part of an urban redevelopment project in Glasgow. The project consisted of five phases: A,B,C,D and E. Each phase was assigned to a different architect, with Sir Basil Spence given responsibility for ”Hutchie C’ in 1959.

The completed tower blocks in Area C (© Courtesy of HES, Spence, Glover and Ferguson Collection)

Spence’s high-rise designs, which included plenty of balconies, were inspired by the drying greens of working class tenements. Spence envisaged that “on Tuesdays, when all the washing’s out, it’ll be like a great ship in full sail”.

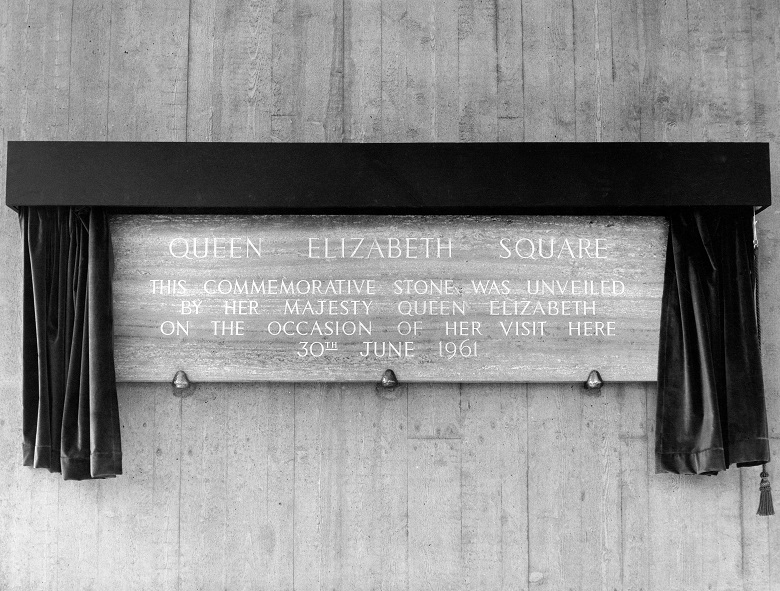

The flats were to be located in Queen Elizabeth Square so, fittingly enough, the Queen unveiled a commemorative plaque on the construction site on 30 June 1961.

A perspective drawing from Spence’s plans (© Courtesy of HES, Spence, Glover and Ferguson Collection)

The commemorative plaque recording the opening of Queen Elizabeth Square (© Courtesy of HES Spence, Glover and Ferguson Collection)

The commemorative plaque recording the opening of Queen Elizabeth Square (© Courtesy of HES Spence, Glover and Ferguson Collection)

Unfortunately, the tower blocks proved too windy for Spence’s “ship in full sail”. What’s more, there were serious issues with damp and maintenance. Despite renovation works in the late 1980s, the city council decided to pull down ‘The Hanging Gardens of the Gorbals’ in 1993.

New, lower flats called Queen Elizabeth Gardens now occupy the site, with distinctive balconies as a nod to Spence’s original vision.

Washing drying in a garden slab in Area C (image from Canmore)

The Burrell Collection: A gallery among the greenery

Located at the edge of woodland in Pollok Country Park, the Burrell Gallery was especially created to house Sir William Burrell’s enormous collection of art and antiquities.

Shipping magnate Burrell bequeathed his treasures to the City of Glasgow in 1944. He instructed that they be housed at least 16 miles from the city to avoid being contaminated by pollution. These conditions were eased when a site near Pollok House (some three miles away) became available in the late 1960s.

242 entries were submitted in a competition held to decide on a design for the new gallery. The winners, Gasson, Andresen and Meunier, made the most of the parkland setting. The interior and exterior of the building get along perfectly with the surrounding landscape.

Construction began in 1978 and the finished product was opened by the Queen in 1983. The building was A-listed in 2013.

The Queen beside the ‘Glasgow Smiles Better’ logo at the opening of the Burell Museum (© The Scotsman, licensed via Scran)

Inside the Burrell Gallery

The Forth Road Bridge: Across the Firth

There’s a Queen Elizabeth Bridge in Aberdeen, but the most iconic crossing that’s linked to the Queen must be the Forth Road Bridge.

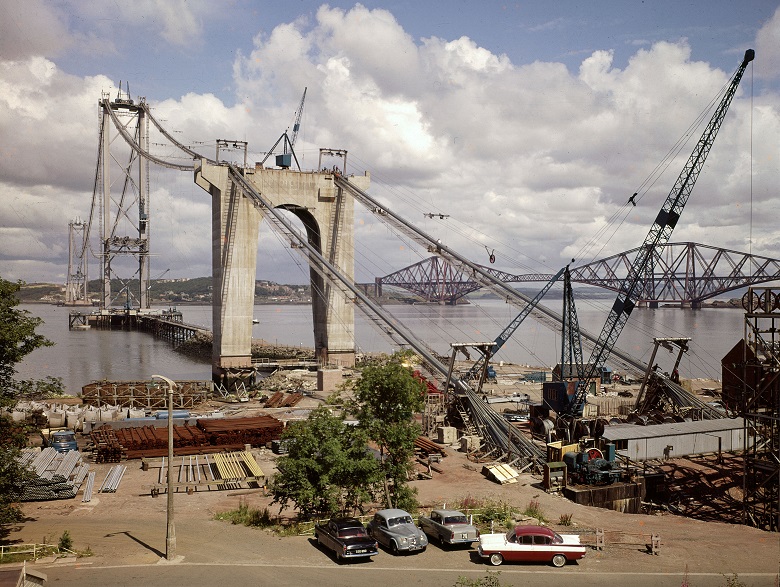

The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh opened the bridge on 4 September 1964. At the time it was the biggest of its kind in the world outside America.

The Queen can be seen in the bottom right of this photo taken from the crowd at the Forth Road Bridge opening ceremony (© Courtesy of HES, Survey of Private Collections)

The opening of the bridge marked the end an 800-year-old ferry service established by another monarch, Queen Margaret. The route between North and South Queensferry was created in the 11th century to carry pilgrims to St Andrews Cathedral and Dunfermline Abbey.

In 2002, the Forth Road Bridge carried its 250 millionth vehicle across the Firth of Forth. It was awarded Category A listed status a year previously.

Cables being spun during the construction of the Forth Road Bridge, 1962 (© Courtesy of HES, Sir William Arrol Collection)

The commemorative stone marking the Queen’s opening of the Forth Road Bridge (© Courtesy of HES, Eric de Mare Collection).

Th Scottish Parliament: “Surging out of the rock”

Directly opposite the Palace of Holyroodhouse, where the Queen hosted an annual garden party, is the Scottish Parliament Building. It was officially opened by the Queen in October 2004.

Built on the site of a former brewery, the distinctive building is the brainchild of Spanish architect Enric Miralles, who died before its completion. 17th century Queensberry House is incorporated within the complex.

The Scottish Parliament and Holyrood Palace from Salisbury Crags

Miralles wanted the Parliament to blend in with the surrounding volcanic crags of Holyrood Park. It should “arise from the sloping base of Arthur’s Seat and arrive into the city almost surging out of the rock.”

The building houses some 129 MSPs and over 1,000 staff, along with a wide range of sculptures and artwork. They include specially-commissioned pieces as well as official gifts from other nations and parliaments.

On the exterior, a series of granite and timber “trigger panels” catch the eye. While they may be simply abstract, it’s thought that they may have been designed to evoke the famous Scottish painting of Reverend Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch.

“Trigger panels” on the exterior of the Scottish Parliament building

What’s on your doorstep?

There are listed buildings of all shapes, sizes and significance across Scotland. To see what’s near you, head to Past Map! You can search for postcodes or specific locations, and compare them against our records and databases.

Alternatively, search for your chosen historic building on our Heritage Portal to find out more about its listed status, architectural value and social significance.

On Canmore, you can see a wealth of images from the National Record of the Historic Environment including archive paintings, photos and plans

For more buildings with royal connections, check out our recent blogs on St Giles’ Cathedral and Edinburgh’s Mercat Cross.