In the late 1990s, during archaeological excavations at Caerlaverock Castle, three small fragments of Islamic glass were discovered.

But what well-kept secret can these tiny shards tell that were found on the hall floor of the ‘old’ Caerlaverock Castle?

A unique discovery

The little shards most likely were part of a drinking beaker. You can still see that the fragments are decorated with Arabic inscriptions. The largest piece includes part of the word “eternal” which means the inscription on the drinking beaker could have been an extract from the Qur’an.

Nowhere else in Scotland have archaeological excavations uncovered glass of this type and origin! The question is: where did it come from?

Through the glass of time

Manufactured glass dates back to around 2500BC and it first appeared in Northern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). The Middle East continued to be the main producer of glass until the later Middle Ages.

The Islamic glass fragments that were found at Caerlaverock Castle date to the 12th or 13th century and may have been made in modern-day Syria, Iraq or Egypt.

Perhaps the drinking beaker could have come to Scotland by trade. Or someone fighting in the crusades may have brought it back here.

Scientific analysis has shown that there would once have been red and gold decorations as well as the blue and white traces which are still visible. These colours were commonly used for glass decoration at the time.

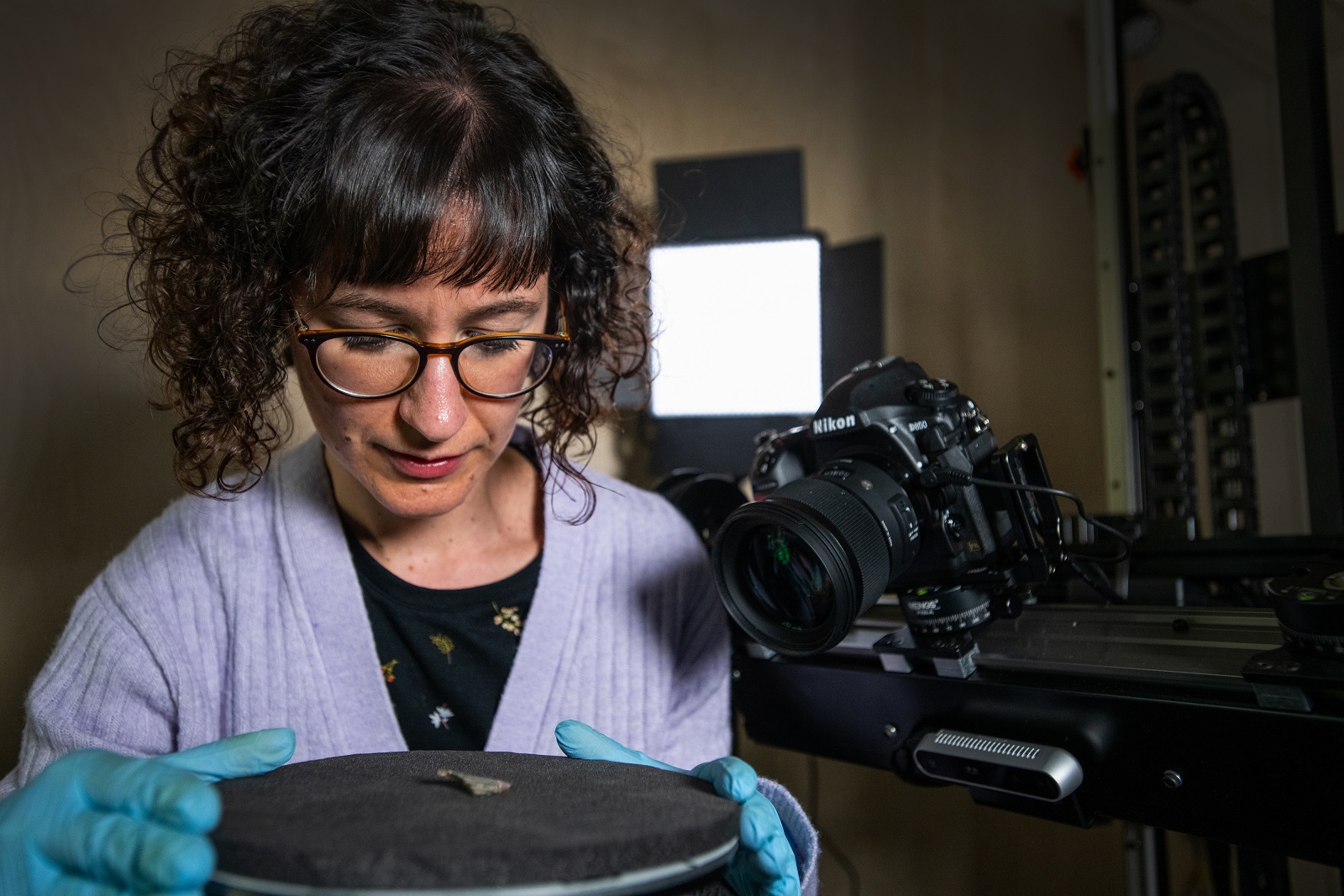

Our Applied Conservation Manager with photogrammetry equipment capturing a piece of the glass.

Under the (scientific) looking glass

Through funding from the AHRC Capability for Collections Fund, we were able to upgrade the heritage science equipment to a portable X-ray fluoresce (pXRF) instrument. The X-ray fluorescence (XRF) technique allowed our experts to identify the chemical elements of the fragment materials without damaging them.

Our Conservation Science Manager uses pXRF equipment with a piece of Islamic glass at the Engine Shed in Stirling

We were able to determine the chemical elements of the glass which gave further clues to the origin of the fragments.

We discovered that soda, lime and silica glass are the basic makeup of the glass. This is very typical for glassmaking in the Middle East in the 13th century.

The origin of the soda in the glass could be a second clue about where the glass is from. There are two types of glass in this form. One type of glass is made using soda from the ashes of plants. The other type uses soda from natron… which is a naturally occurring salt from Wadi Natrun in Egypt!

A place in time

In partnership with Glasgow-based Muslim women’s centre Amina, Edinburgh Muslim Scouts group 8th Braid Salaam Scouts and digital artist Alice Martin, we delved deeper into Scotland’s connections to Islam and the Middle East in our past, present and future.

Together, the group learned more about the origin of the pieces of glass and explored Muslim heritage and identity in Scotland today.

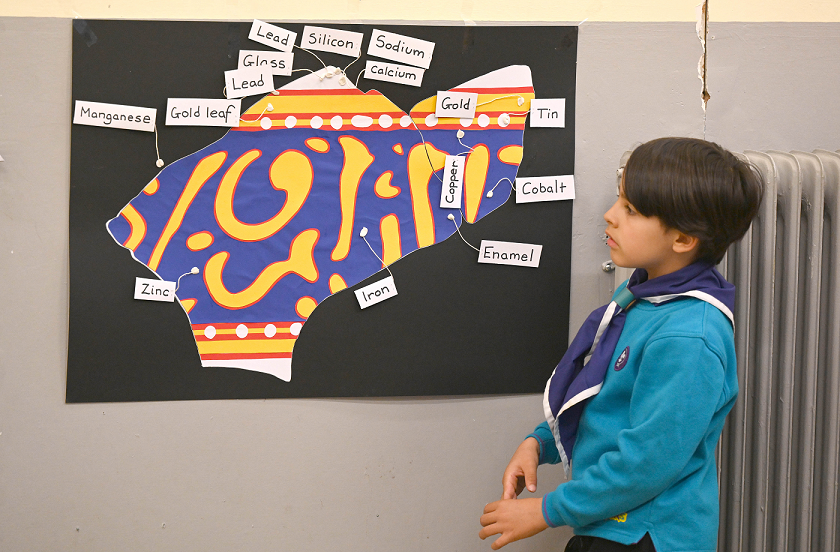

The young people from the 8th Braid Salaam Scouts explored the history and scientific discoveries of the Islamic glass

This is a journal entry that one of the participants from Amina wrote. It’s a creative writing piece from the perspective of the glass vessel:

نمیدونم اهل کجا هستم در بچگی زمان جنگ من رو از خانوادو کشورم دور کردن ولی از نشانه های

روی بدنم به نظر میاد عرب باشم

من الان در گلاسگو هستم از یه طرف خوشحالم که دارن تلاش میکنن اصالت منو پیدا کنن

از یه طرفم نگران که شاید هیچ وقت به نتیجه نرسن

Translation:

Hello, I am a glass fragment that you visited the other day. My name is Plate.

To be honest I don’t know where I’m from. As a child, I was separated from my family and country. But from the markings on my body, I imagine I’m Arab. I am in Glasgow now.

On one hand, I’m happy that scientists are trying to find my origins; on the other hand, they may never succeed.

I have a feeling that pieces of my body are buried, perhaps if they are found, it can be the beginning of finding me.

One of the key questions our group pondered was of course, how the glass ended up in Scotland. But we also wanted to find out what the drinking beaker might have looked like.

With the scientific pXRF analysis, historic context and other discoveries of 12th-13th century Middle Eastern drinking vessels Alice was able to create a 3D reconstruction of the glass. Have a closer look!

Looking for more?

Working with Amina and the 8th Braid Salaam Scouts, our Eternal Connections project used funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Capability for Collections Fund to find out more about the fascinating discovery of the Islamic glass at Caerlaverock Castle.

While we may never know how the fragments ended up in Scotland, they can serve as a looking glass into our shared history with the Middle East.

There is much more to explore! Find out more about the exciting find of the glass and the Eternal Connections project on our ThingLink.

Click here to view the accessible version of this interactive content

Header image: © Crown Copyright Reserved Historic Scotland.

There are many more fascinating objects in our archaeological collections and you can continue the exploration on our blog.