If you’re looking for some memories of your schooldays, or have an interest in academia and architecture, then we’ve got a top-of-the-class treat for you! We’ve been doing our homework on Scotland’s historic high schools, many of which are (or were) housed in impressive and equally historic buildings.

We know that these buildings have a distinctively Scottish character but we’re yet to tell their stories in detail. To fill that gap, we’ll be publishing 20 detailed essays dedicated to the best examples. Read on for a taster of what’s included.

Spotting historic high schools

The former Bathgate Academy showing its clock tower and linking colonnades

When it comes to spotting historic school buildings in our towns and cities, it doesn’t help that many of them aren’t actually schools any more! But they often survive relatively intact in new uses, with many recognised as listed buildings.

After closing, historic schools were often kept in public control and reused for learning communities. A good example of this is Farraline Park in Inverness (designed and built 1839-41), which became a public library. The retention and re-use of these old buildings reflects a town’s pride in their surviving publicly-funded high school buildings.

Many fee-paying schools have remained in their original stone historic buildings. The old buildings represent the school’s long history and traditions, and this can attract parents and guardians.

What’s in a name?

A marble statue of the founder of Robert Gordon’s College. Gordon was a wealthy merchant in Aberdeen. The statue was by sculptor J Cheere.

Confusingly for us today, what we call ‘high schools’ were originally known by lots of names. You might come across burgh schools, town schools, grammar schools, proprietary academies and institutes. There were also endowed hospital-schools which became fee-paying day schools.

You’ll find that many of the the earliest school buildings in Scotland were for fee-paying schools, at least originally. High School education had to be paid for – but the fees were modest.

Our Scotland’s Historic Town Schools project uses new research and analysis to cover all of these types of school from the 1700s up to the 1880s.

Educating the people

Staff in front of the main building at Harlaw Academy in the 1890s, when the school was known as Aberdeen High School for Girls. (© Harlaw Academy, reproduced courtesy of Harlaw Academy)

The oldest school we’ve looked at is Robert Gordon’s College in Aberdeen, which opened in 1731. The oldest surviving day school is the Haddington Burgh School, established in 1755.

Our main focus, however, is on the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. At this time, there was an expansion of secondary education and new schools were built across Scotland. These new school buildings belonged to a period before the standardisation of a national education system in Scotland. Individual school histories, often authored by teachers, have been an important and useful resource.

Our essays don’t just cover the architecture of the buildings. They also explore the educational and institutional history of our historic schools, answering questions about how the new schools were funded, who governed them and what subjects they taught.

Surveying historic high schools

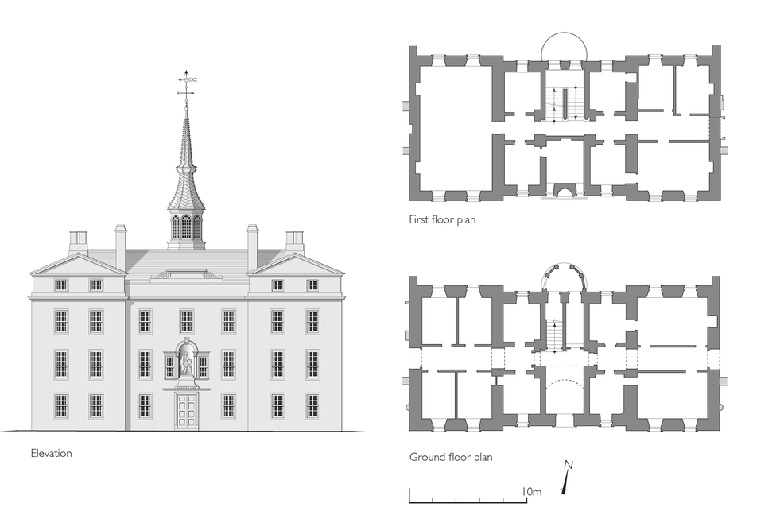

A digital drawing from 2001 of the ‘Auld House’ building at Robert Gordon’s College, Aberdeen. It shows the front of the early eighteenth century building and the reconstructed plans of each floor. The drawing was based on our detailed measured survey of 1998.

Once we’d chosen the historic school buildings to explore, they were visited and surveyed in great detail by HES colleagues. This included photography and measured survey which resulted in plans, and beautiful elevation drawings. We aim to understand the ‘life’ of the building.

Each essay uses this information to tell the story of the design and use of the original buildings, and also of any later buildings which have been added over the years. These old buildings conceal many stories from Scotland’s complex and every-changing educational past.

Grand designs

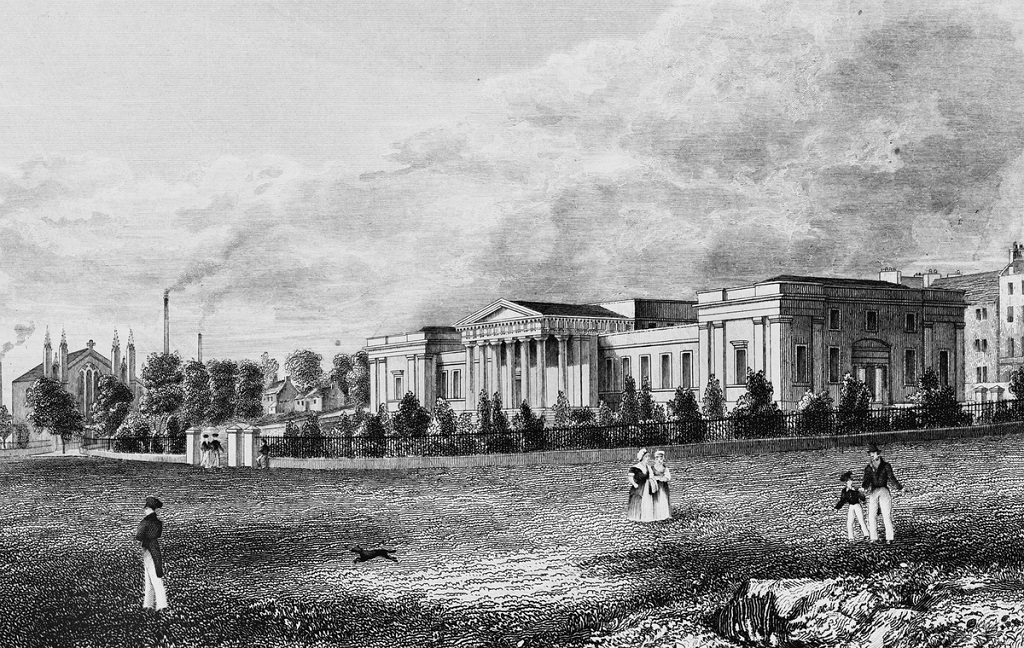

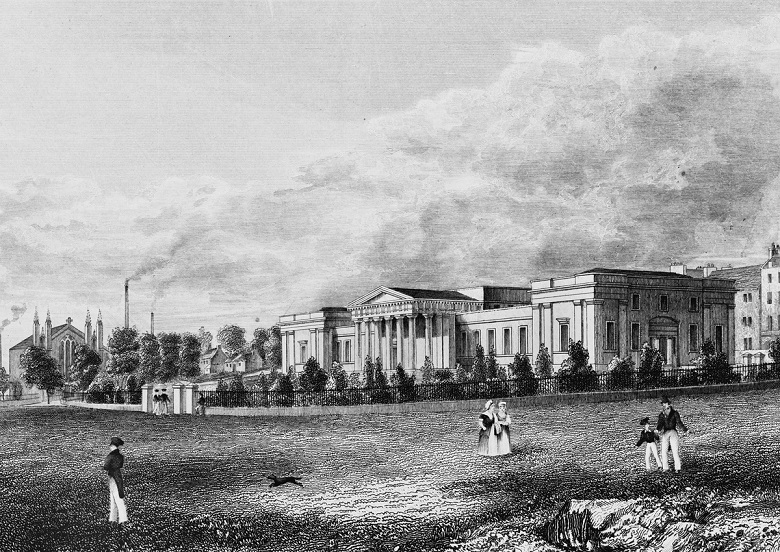

An engraving of Dundee High School c.1836 by Joseph Swan

So what have we uncovered? Firstly, we know that all the school buildings were designed by leading national and regional architects and were high status public projects.

Variations of the revived classical styles dominated school design, especially for public-funded burgh and town schools. It ranged from modest to highly decorated classic styles. Early examples include imposing school buildings which were classically formal and regular in plan such as Haddington Old Grammar (1755) and Stirling Old Grammar (Gideon Gray, 1788).

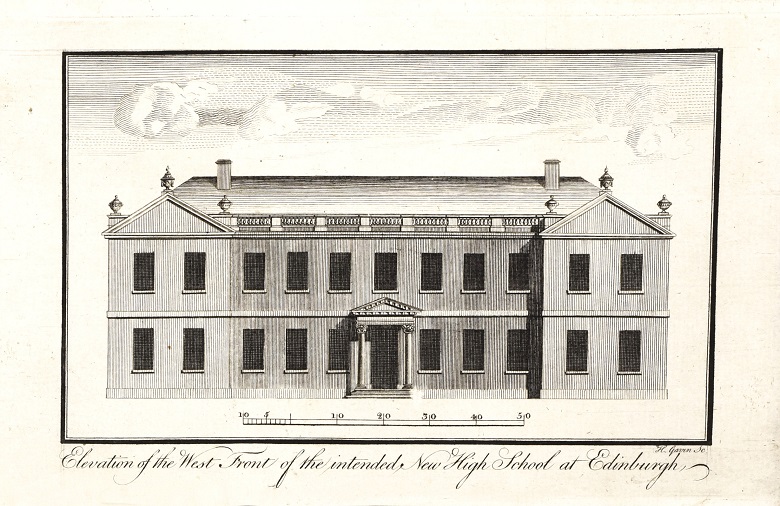

The ‘model’ burgh school became the stark neo-classical Old High School of Edinburgh (1777), designed by architect and mason Alexander Laing. It provided a common plan-type for ground and second floor classrooms and a large hall. Laing’s flat-fronted regular classical facade was described as being “void of all superfluous ornament”. Laing produced a similar design for Inverness Royal Academy (1792). His formula was quickly adopted by burgh schools throughout Scotland, such as Royal Tain Academy (1810-13, J Smith).

Temples of learning

An elevation drawing by Alexander Laing of the west front of the new High School of Edinburgh. It was included in a pamphlet of 1777 which aimed to raise money to build the school. (Crown Copyright, National Records of Scotland)

This architectural formula was in time adapted to create more sculptural neo-classical stylistic fashions.

Greek revival designs of the 1820s and 1830s boasted large columned temple fronts. They can be seen at wealthy academies like Dollar Academy (1820, William Playfair), and Bathgate Academy (1831, R & R Dickson), and Edinburgh Academy (1822-4, W Burn). The architectural peak was Edinburgh Royal High School. It was Scotland’s foremost historic school when its new school building was designed and built on Regent Road by Thomas Hamilton in 1825-9.

By the mid-nineteenth century revived Tudor and Jacobean styles dominated. For example, William Burn’s revived neo-Jacobean Madras College, St Andrews (1832) was set round a courtyard in the style of George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh. In turn, Italianate and Baronial styles were also revived for new schools.

Want to see more historic high schools?

If this brief introduction has served to whet you academic or architetcural appetite, five of our essays on historic high schools are available online right now!

Head to Canmore to download our features on Harlaw Academy in Aberdeen; Robert Gordon’s in Aberdeen; Bathgate Academy; Dundee High School and Edinburgh High School.

For more education history, see our short history of Donaldson’s School for the Deaf or the remarkable story of Britain’s first Black school teacher. For a more modern Scottish school, check out memories of Craigmount High on Canmore.