Stirling Castle, 1507

Up in his study, the High Treasurer of James IV reviews his records. A lot has been spent on the royal festivities this year: delicious banquets, lavish celebrations and of course, magnificent music. The King insists that the palace should never fall silent, and that exquisite music is the sign of a powerful court.

His performers must be highly skilled musicians, educated in the best musical families of Europe and Africa, as in the vibrant courts of Islam many centuries ago.

The High Treasurer can’t help but think about one of those musicians, who died a few months ago under the care of the King, a perfect example of that cosmopolitan excellence. A drummer.

Was he Scottish, born to a parent of African heritage? Was he foreign, coming from the courts of Spain or the Empire of Mali? The Treasurer doesn’t know.

He looks through the pages…What was his name again?

‘The More Taubronar’

The musician of our story is known to the records as ‘The More Taubronar’. He was a musician of African ancestry who served at the court of James IV in the early 16th century.

His name is unknown, but the word “More”, “Moris” or “Moryen” was commonly used in Renaissance Europe to refer to people of African or Moorish ancestry, encompassing many cultures from the African continent. The article ‘The’ introducing The Taubronar’s title is usually an indicator of origins or possible ancestry. Other examples are ‘the French gardener’ or ‘the Italian minstrels’.

‘Taubronar’ was his trade. He played the tabor drum, a versatile instrument used equally for courtly music as for military calls on the battlefield.

The Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland are a spectacular source of information to picture life at James IV’s court which was a diverse and cosmopolitan place in the early 16th century. It also gives us precious details on ‘The More Taubronar’ such as his wages, clothes and aspects of his work as a royal musician.

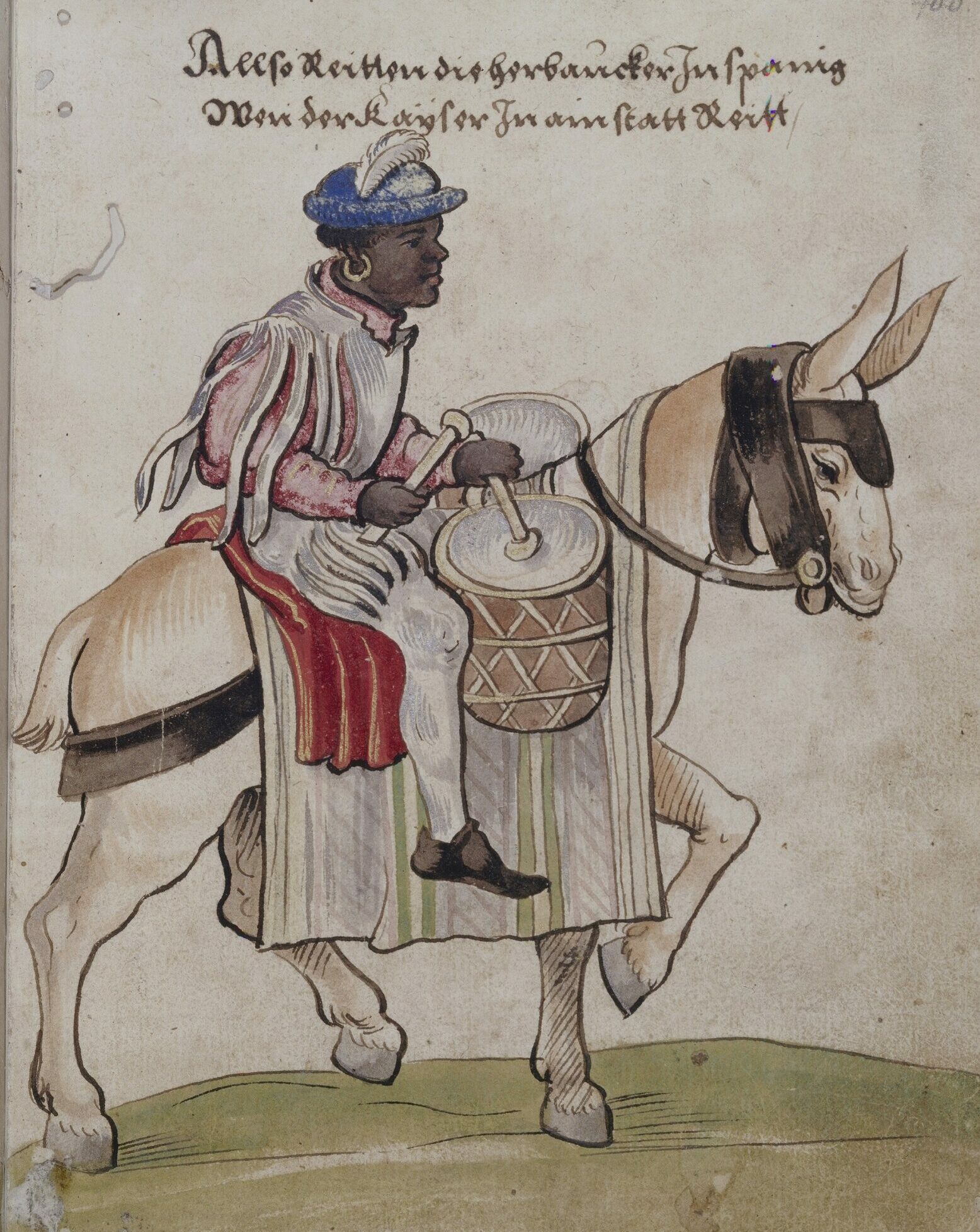

The German painter and medalist, Christoph Weiditz, illustrated ‘Heerpauker beim Einzug des Kaisers’ in 1529. He made this drawing and others on his visit to Spain capturing folk costumes the inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula. It’s a rare depiction as far as we know but it shows that musicians from Africa were not uncommon at European courts.

Musician of the Court

Music was everywhere at the court of James IV. Celebrations, dancing lessons, funerals or tournaments – a wealth of instruments would signal the beginning of events, accompany prayer and entertain the court. African musicians played across European courts, inspired by the traditions at medieval Islamic courts.

Employed all year round, the royal musicians followed the King and his entourage as they journeyed from one palace to another. ‘The More Taubronar’ played for James IV at Linlithgow Palace, Dumfries and Falkland between 1505 and 1506. He performed at royal events such as banquets, tournaments, and festivals. Much like other trades, families passed on their musical skills from generation to generation.

Linlithgow Palace was a place of many feasts and ‘The More Taubronar’ also performed at the pleasure palace. This illustration shows the preparations that were underway for the celebration of Easter and the birth of James V in 1512.

The Royal Livery

Dressed in colourful and expensive silks, ‘The More Taubronar’ appeared to his audience in a luxurious livery (his working uniform) identical to that of his colleagues.

This could indicate that the taubronar’s cultural heritage and possibly darker tone of skin made no difference when it came to official clothing. Thus, enhancing professional occupation over individualities.

Elegant clothes were part of a musician’s wages and were a reflection of the King’s prestige.

An Attractive Position

‘The More Taubronar’ was paid 4 pounds, 7 shillings and 6 pence per quarter. That’s a good salary considering he also received food, accommodation, clothing and money for his additional expenses, all paid for by the royal treasury. This was a privilege that would have attracted many talented performers from Scotland and abroad.

It is unclear what happened to the taubronar and his instrument. But in 1505 he received an extra payment from the King’s treasury to repaint his drum. Was it because of an accident during a celebration, or simply because of the wear and tear of his demanding profession? In any case, this was considered a necessary expense for the royal treasury.

Artists From Abroad

Pipes, drums, trumpets, Islamic lutes and Spanish guitars – music in the Renaissance was a vibrant, multicultural stage. ‘The More Taubronar’s’ presence at the Scottish court continued a long medieval tradition of African musicians playing for the monarchs of Europe.

Several of his colleagues shared a foreign heritage, like the group of ‘four Italian minstrels’ with whom he worked in a close relationship. They must have performed regularly with the taubronar, as the records show the five of them paid as a group on several occasions, such as an exceptional event in 1505 during the Easter festivities, when the taubronar and his colleagues were to form an extensive group of 19 musicians, including harpists, lute players and additional drummers.

© National Galleries of Scotland Licensor www.scran.ac.uk. King James IV valued an international flair at his court. There are many references to foreign people at Scottish courts, including French, Italian and African musicians and courtiers.

‘The More Taubronar’, A Man With No Name

‘The More Taubronar’ is part of a large group of unidentified characters in the Royal Treasury Records, known by a description rather than a name. Some were described by their occupations (‘maister cook’, ‘messengers’), their condition (‘blind harpist’), and origins (‘the French gardener’).

Some, however, will remain a complete mystery to the modern reader, such as the ‘woman who brought strawberries to the King’. The motives behind this partial recording process are unclear, as our Renaissance ancestors often gave more importance to social class and Christianity rather than ethnicity.

The taubronar’s fellow drummer Guilliem, whose name might suggest a possible foreign origin and who was paid the same wage, is identified by his own name as well as several other musicians. Was it a difference in class? A manifestation of prejudice against one type of ‘foreigness’ over another, based on The Taubronar’s darker complexion? Did the High Treasurer know Guilliem personally?

During the same period, the two ‘Moorish Lassies’, Elen and Margaret, and the courtier ‘Peter The Moor’ were also African-Moorish presences at the Scottish court, mentioned by name. Did their higher rank make them more memorable?

End of Life

‘The More Taubronar’s’ life took an unexpected turn in June 1506 when he got injured in an accident. We find medical expenses in the treasury records, including two treatments of leeches. Despite those efforts, he unfortunately died and left his wife and child without resources.

His death, or at least long-term incapacity appears indirectly in the records when his precious instrument was given to another drummer. Following this, two payments were made to ‘the Moris wife and his child’ in 1507. This was possibly a way for the King’s household to help the family in this difficult time.

Those payments are also the last mentions in the treasury accounts of ‘The More Taubronar’, giving a final end to the thread of information about his life.

So much is still unknown about the ‘More Taubronar’, including his years at the Scottish court. It remains an elusive tale.

While most of the information on this blog are based on the study of ‘The Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland’, this text owes much to the work of Miranda Kaufman and her book ‘Black Tudors’ (2017) for the context of royal musicians at European courts.

About the author

Virginie Chaverot works at Stirling Castle for the interpretation team of Living History Scotland. All year round, she is producing and presenting to the visitors embroideries telling the stories of Scottish and English Africans in the Renaissance era.

Scotland’s Black History on our Blog

This is one of many stories from Scotland’s Black History. Have you ever heard of Scipio Kennedy and how he came West Africa to Ayrshire? Or do you want to find out how Dorothea Thomas, a young woman from Grenada, changed Scots law?

If you want to get the latest from our blog straight to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletter

Header image: The magnificent Great Hall at Stirling Castle is the largest of its kind ever built in Scotland. Completed for James IV in 1503, it was used for feasts, dances and pageants. The illustration shows the banquet for Prince Henry in 1594 held by James VI.