You may associate Stirling Castle with battles, sieges, and a long military presence, but there’s another side to its story that is just as enduring and important. The history of everyday family life.

From the 1100s onwards the castle was a seat of royalty. Scottish monarchs implemented expansion, fortification, and rebuilding projects over the centuries. Their power was inextricably tied to dynastic politics, so Stirling’s developing role as a family home was central.

The Wars of Independence: A Dynastic Struggle

The castle’s strategic location, with commanding views over the Forth valley, made it a crucial target in the Wars of Independence.

It all started with the death of Margaret of Norway, the granddaughter and heir of Alexander III, in 1290. Scotland was left without a monarch and different noble families contended to show that their familial claim to the crown was the strongest.

Margaret of Norway depicted in stained glass at Lerwick Town Hall.

The conflict developed into a struggle between the Bruces, headed by Robert I and his son David II, and John and his son Edward Balliol, supported by the kings of England. All four were inaugurated as king by their rival factions.

Early in the conflict, in 1306, Robert’s wife Elizabeth de Burgh, his daughter Marjorie, and his sisters Christina and Mary were captured and imprisoned in England. In 1314, the Battle of Bannockburn was fought nearby for control of Stirling Castle. Having triumphed, Robert had his family members released. He and Elizabeth were now able to produce their heir, the future David II, to eventually secure the crown for the Bruce dynasty.

However, David didn’t have children with either of his wives, Joan of England or Margaret Drummond. He installed his girlfriend Agnes Dunbar in Stirling Castle in 1370 but died without heirs. The crown – and the castle – were inherited by his nephew, Robert II: the first monarch of the Stewart dynasty.

Medieval Family Fortunes

Stirling was a bustling centre of court and political life. This reconstruction shows how the King’s Old Building may have looked in the time of James IV.

The royal family spent much of their time at Stirling, making it a centre of court and political life in the 1400s and 1500s. Royal children spent their formative years here, including the young James II and his six sisters, Margaret, Isabella, Mary, Joan, Eleanor, and Annabella.

The Exchequer Rolls – financial records including money spent on the royal household – give an insight into the children’s daily lives. An entry from 1444, for example, describes how they were provided with three casks of wine, 49 dried Orkney pigs, two barrels of beer, six barrels of rye flour, woollen cloth, linen, saddles, harnesses and arrows. Such evidence suggests not only that the prince and princesses were well fed, but that they engaged in the traditionally elite pursuits of riding and hunting.

Fit For A Queen

The Castle became one of the properties traditionally granted to the queen consort as part of their dower: estates they would inherit in the event of their husband’s death. The dower of Mary of Guelders, queen of James II, included “Stirling Castle; the great customs and burgh fermes [rents] of Stirling with the office of sheriff of the sheriffdom,” and assorted lands within the sheriffdom. Mary inherited Stirling on her husband’s death, as did later queens Margaret Tudor and Mary of Guise.

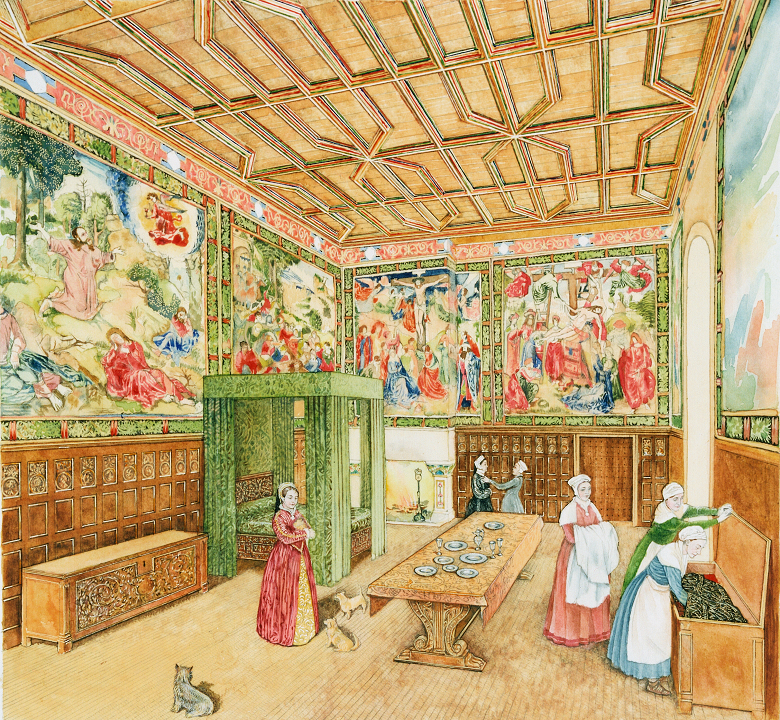

A reconstruction of the Queen’s Bed Chamber at the time of Queen Mary of Guise.

Records of the birthplaces of royal children don’t always survive, but one that does is that of Mary of Guelders’ first child, a daughter, born at Stirling Castle in 1450. She was born prematurely and died shortly afterwards.

A later 15th-century queen, Margaret of Denmark, raised her three sons at Stirling. Her husband, James III, preferred to live in Edinburgh. She had her children, including the future James IV, serve her at table so that “they should be graced with manners both royal and courteous” and treat their own servants well.

On Margaret’s deathbed, she allegedly said,

James, my eldest boy, I am speeding towards death; I pray you, through your obedience as my son, to love and fear God, always doing good, because nothing achieved by violence, be certain, can endure.”

Margaret died at Stirling in 1486.

She was likely aware of growing tension between father and son. Just two years later, young James took part in the rebellion which led to his father’s death at Sauchieburn, close to the castle. Both of James IV’s parents were buried at nearby Cambuskenneth Abbey.

A Nursery for Royal Children

James IV grew up to be something of a ladies’ man, with several girlfriends and at least seven illegitimate children. For five months of 1496 Margaret Drummond lived at Stirling Castle in her own apartments. The Spanish ambassador reported,

When I arrived, he was keeping a lady with great state in a castle. He visited her from time to time.”

Janet Kennedy was residing at Stirling with James when she gave birth to their son, also James, in 1501. A nurse was employed, Janet received expensive textiles like velvet and damask, and the baby was given an embroidered chrisom cloth for his baptism. About a month later, bread and oatcakes were provided for “the ladyis upsetting feast” to celebrate the birth.

The following year, Janet had her and James’s second child, a girl whose name is unknown, also at Stirling. The accounts record money spent on sumptuous fabrics for her cradle and on the baptism. The baptisms of these children likely took place in Stirling’s Chapel Royal. This building would be demolished in the 1590s to make way for the present Chapel Royal.

With the arrival in 1503 of Margaret Tudor, James’s 13-year-old queen, the king no longer lived openly with his girlfriends. His children continued to reside at court, at least for a time. James and Janet’s young daughter died at Stirling while James was in Edinburgh celebrating his marriage.

Alexander (James’s son by Marion Boyd) and James, earl of Moray (his son by Janet Kennedy) were educated at Stirling. However, in 1504 Alexander, around 11 years old, was nominated as archbishop of St Andrews. He then undertook further education on the continent under Erasmus and at St Andrews. The young James’s household was also moved to St Andrews, and he later joined his half-brother Alexander in Italy.

Grand Baptisms (and beds!)

Interior of the Chapel Royal, set up for a function (© Marc Millar)

Margaret Tudor and James had six children, though only one – the future James V – survived infancy. Unfortunately, their sons James (an older brother of James V) and Alexander, who was born after the king’s death, died at the castle.

James V took after his father in his prolific love life, having at least nine children with numerous women. They mostly grew up with their mothers, but Jean, daughter of Elizabeth Beaton, was a member of the household of James’s second wife, Mary of Guise. Records show that Jean slept in a luxurious wooden bed with a feather pillow and a tapestry canopy, wearing silken nightgowns lined with fur.

Royal Ceremonies at Stirling

An artist’s interpretation of Mary, Queen of Scots’ coronation

James V had two sons with Mary of Guise. The younger, Robert, was born at Stirling, but both died in infancy. His one surviving legitimate child, Mary Queen of Scots, is most strongly associated with Stirling Castle.

The castle’s prominent position, and its use as a family home for royalty, made it a natural location for important ceremonial events.

The Chapel Royal was where both James V and Mary Queen of Scots were crowned , in 1513 and 1543. Both coronations took place during times of Anglo-Scottish turbulence. The monarchs were only infants, and the castle was a suitably safe but also grand place from which to proclaim the power of the Stewart dynasty.

Mary spent her early childhood at Stirling in the care of her mother, Mary of Guise. During the “Rough Wooing”, English forces invaded Scotland to try to force a marriage between Mary and Edward VI of England. She stayed safe within Stirling until 1548, when she was sent to the French court.

Mary and James

After Mary returned to Scotland she had her own child, the future James VI. It was at Stirling’s Chapel Royal that she chose to have him baptised in 1566. Mary’s half-sister Jean, now countess of Argyll, stood in as godmother for the absent Elizabeth I of England. Courtiers and foreign ambassadors were treated to three days of banquets, masques, fireworks, and a mock siege of a fortress outside the castle walls .

Mary entrusted the care of baby James to John Erskine and Annabella Murray, earl and countess of Mar. He was “to be conservit, nurist and upbrocht within our said Castell of Striviling under [their] tutill and governance”, alongside their own children.

When James was 10 months old, Mary tried to take him with her from Stirling to Edinburgh. But it was a turbulent time in her reign. She was suspected of involvement in the murder of her husband, Lord Darnley. The Mars refused to allow her to take her son. This was the last time she ever saw him; soon after, she was forced to abdicate and escaped to England.

A Happy Home?

James VI spent his whole childhood with the Mars at Stirling Castle. He was crowned not in the Chapel Royal, which may have had too many Catholic associations for the increasingly Protestant ruling class, but in the Kirk of the Holy Rude, just outside the castle walls. The infant king was carried there, dressed in crimson and blue velvet and taffeta, by Annabella.

James’s childhood was disrupted by the Marian civil war, in which his supporters struggled for control against those of his still-living mother, Mary. In 1571 the regent, James’s paternal grandfather, Matthew Stewart, earl of Lennox, was shot during a brawl which broke out during a session of parliament.

A portrait of the young James VI.

Lennox died in the castle. His final words were said to have shown concern for young James and love for his wife, Margaret Douglas:

remember my love to my wife Meg, whom I beseech God to comfort”.

He was buried within the castle, either in the Chapel Royal or in the chapel that once stood on the site of the Governor’s Kitchen, at the corner of the King’s Old Building and the Palace. Margaret commissioned an elaborate monument to her husband, but it no longer survives.

When the time came for James VI to marry and produce his own children, his wife, Anna of Denmark, gave birth to their first child in Stirling Castle in 1594. Henry Frederick was, like his father, baptised in the Chapel Royal , which was rebuilt especially for the occasion.

Henry was also raised by the Mars. The 1st earl of Mar had died but his widow, Annabella, and their son, John, looked after the young prince.

The End of an Era

Stirling Castle’s role as a family home for royalty came to an end in 1603. James VI inherited the throne of England and the court relocated to London. He returned only once, during a visit to Scotland in 1617. On his entry into Stirling a local official, Robert Murray, made a speech:

“This Towne, though shee may justlie vaunt of her naturall beautie and impregnable situation, […] though shee may esteme herselfe famous by worthy founders, re-edifiers, and the enlargers of her manie priviledges, […] yet doeth shee esteme this her onlie glorie and worthiest praise, that shee was the place of your Majestie’s education, that those sacred brows, which now bear the weghtie diademes of three invincible nations, wer empalled with their first heere”.

Stirling’s place as the childhood home of royalty clearly remained important to local people. The castle had played a pivotal role in Scottish history as the setting for both dynastic celebrations and everyday domestic life.

It was a nursery for kings and queens but also for lesser-known, illegitimate children, who were valued members of the royal household. Stirling Castle was a place of birth, life, and death. It gives us an insight into the intimate personal lives of the great and the good.

Discover More

There’s plenty for the whole family to enjoy at Stirling Castle today, too!

On your next visit you can follow a family trail in the Unicorn’s Garden, or take our fact-finding quiz. There’s also a chance to chat with our friendly costumed interpreters. They’re always happy to give you a glimpse into what life at the castle was once like.

And look out for our brand-new Stirling Castle guidebook, which will be hitting the shelves soon. It’s packed full of fascinating facts and research, just like this blog! If you want more Stirling stories right now, there’s more in our dedicated blog category.