⚠️Content warning: This post contains details about the murder of a woman and includes graphic descriptions of violence against women⚠️

Pittenweem is a little fishing village in Fife. In 1704, it became the centre of rumours that culminated in the lynching of Janet Cornfoot.

Those suspected of her murder were never charged, but the events in Pittenweem went down as one of Scotland’s most unusual witch hunts.

© Courtesy of HES (Joseph Swan). Appearing in records in 1228, Pittenweem’s port harboured a thriving fishing fleet, and was home to merchants trading with the Low Countries. This illustration shows a view of Pittenweem Harbour from 1840. Zoom in on Canmore

Our story begins when Beatrix Layng visits 16-year-old Patrick Morton, working at his father’s blacksmith shop, to ask if he can make her some nails.

When Patrick refuses as he has to complete an urgent job for a ship in the harbour, Beatrix angrily leaves the shop, allegedly threatening revenge.

The next morning, Patrick reportedly notices a bucket of water with burning coals next to Beatrix Layng’s house. Upon the discovery, Patrick claims he feels weak and becomes ill. He takes this as a sign that Beatrix has cursed him.

In the following days, Patrick is said to start suffering from heavy convulsions and seizures. Local physicians can’t identify a cause. This is when the speculation of witchcraft starts to spread.

Beatrix already has a reputation for being a troublesome neighbour, which fuels rumours about her supposed involvement with the Devil. She immediately becomes the target and centre of the witchcraft allegations…

He said, (s)he said – Pittenweem’s witchcraft investigations

The local minister, Patrick Cooper, was on a mission to expose alleged witches, obsessed with uncovering the Devil’s work. When Patrick Morton became ill and the rumours of a curse started to spread, the minister began visiting Morton.

Shortly after Morton accused Beatrix Layng of witchcraft, he named several accomplices: Isobel Adam, Janet Cornfoot, Nicolas Lawson, Lillie Wallace and Janet Horseburgh. It’s likely he was influenced by the minister, who pressured the boy to make these accusations against the women.

The minister and the authorities swiftly imprisoned the accused in the Pittenweem Tolbooth, neighbouring the parish church. Under torturous ordeals led by the minister including sleep deprivation, beatings and witch pricking, Layng eventually confessed to working with the Devil and casting spells.

In her confession, Isobel Adam implicated a seventh person – Thomas Brown. Thomas was questioned as well but never confessed to the witchcraft allegations. Still, he was imprisoned in the Pittenweem Tolbooth and later sadly died of starvation.

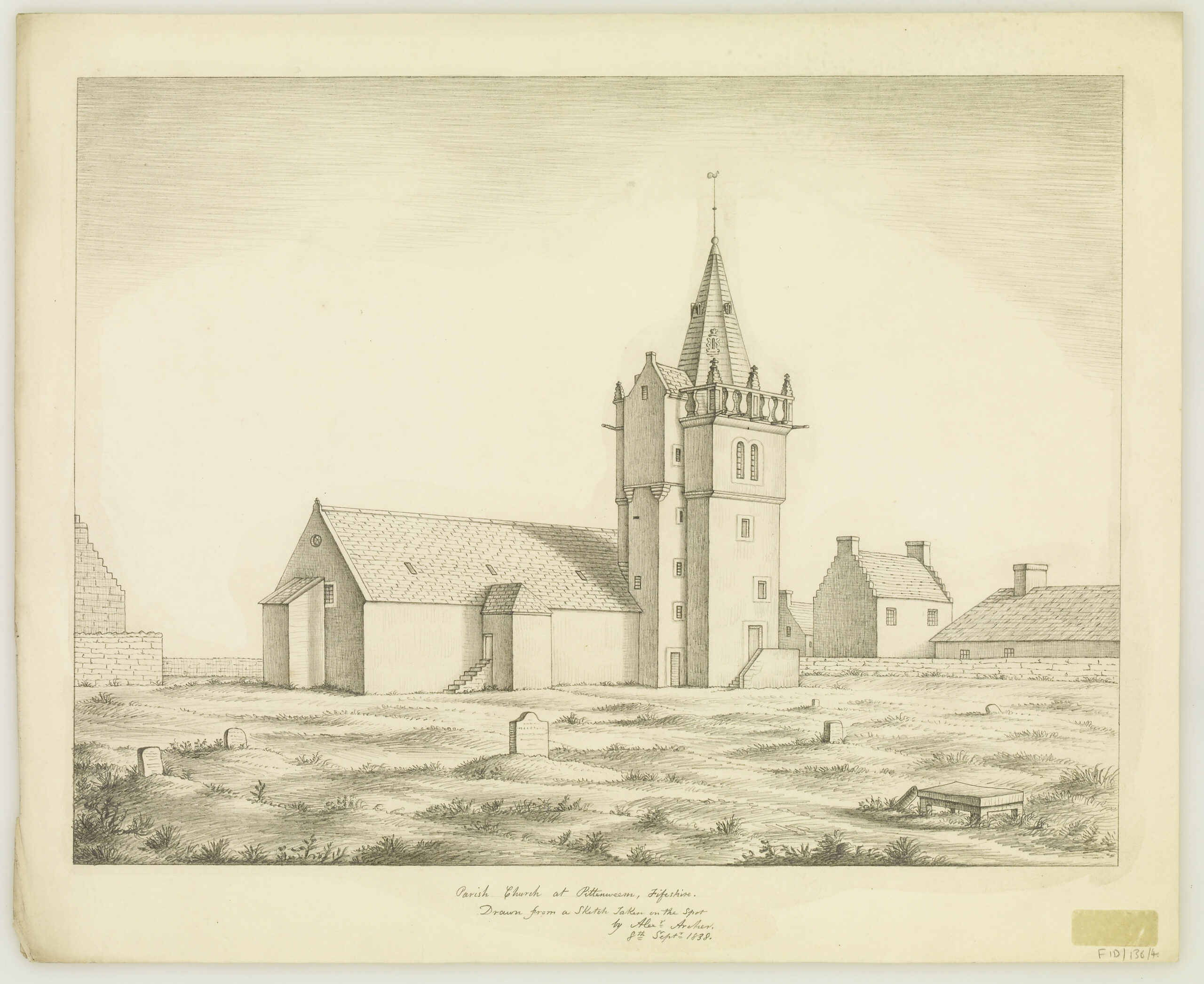

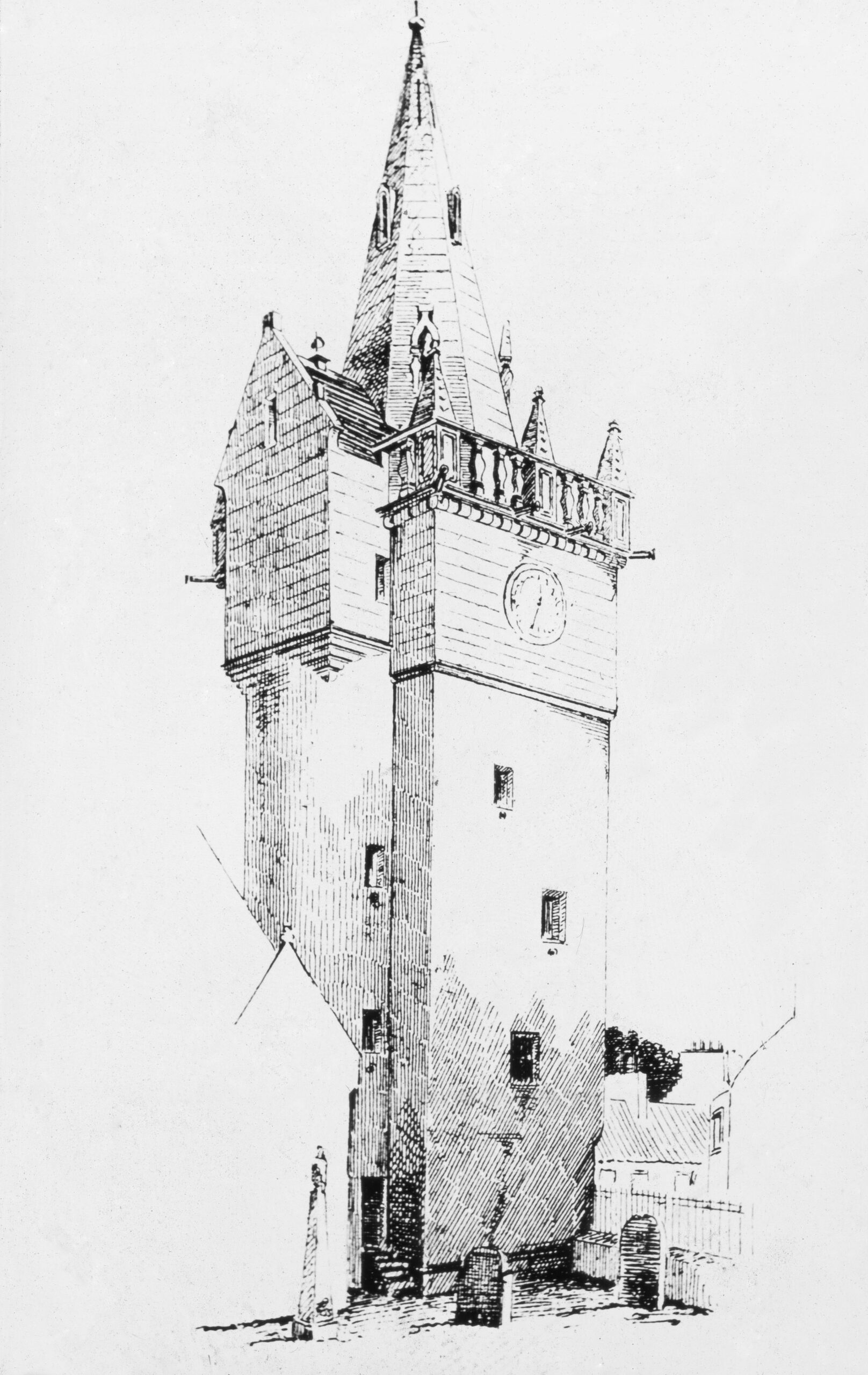

© Courtesy of HES (Alexander Archer Collection). This sketch from 8 September 1838 shows a view of the Pittenweem Parish Church and the Tolbooth Steeple by artist Alexander Archer. Take a closer look on Canmore

Beatrix Layng, Isobel Adam, Janet Cornfoot and Nicolas Lawson were interviewed on 29 May and confirmed their statements. Janet Horseburgh and Lillie Wallace, however, maintained their innocence.

Misogyny was an integral part of the witchcraft investigations and trials at the time. It was a common belief that women lacked the willpower of men and were therefore easily tempted by the Devil. The intimate, often violent methods of detecting a suspected witch and the trials were often carried out by male-dominated authorities.

Janet Cornfoot’s tragic escape from Pittenweem

After several months in prison, all women except for Janet Cornfoot were either freed or released after paying a fine.

Cornfoot remained in the Pittenweem Tolbooth, in solitary confinement. It is said that one of the guards took pity on Janet and put her in a cell with a low window, just small enough for her to escape.

© Courtesy of HES. Pittenweem’s Parish Church and its Tolbooth’s steeple is now a category A-listed building. But in 1704, this was where Janet Cornfoot and the other accused witches were held and tortured. Explore our Canmore images of Pittenweem Parish Church

Janet fled from the village, but the taste of freedom didn’t last long. She was captured and returned to Pittenweem on 30 January 1705, and brought to the house of a local bailiff.

News of Janet’s return travelled fast, and a mob of blood-thirsty villagers formed. What happened next is unclear, as interpretations of these events vary. According to the most cited account, the villagers entered the house, tortured Janet, tied her up and dragged her to the harbour. At the harbour, they hoisted her up on a rope to stone her.

Eventually, the growing group of villagers pulled Janet down and lay a door and heavy boulders on her, crushing Janet to death.

To finish off their murderous spree, the mob drove a horse and cart over her body to ensure Janet was really dead. Her body, along with that of Thomas Brown, was thrown into a communal grave as the minister denied them a Christian burial.

The aftermath

This is the only documented lynching of an accused witch in Fife. The events could have been inspired by the Salem witch trials that took place around ten years before. At the Salem witch trials, pressing was used against a suspect who would not confess.

It’s worth noting that by the 18th century there was growing scepticism around witchcraft and the brutal methods authorities had deemed effective in exposing it. After over a century of witch hunts, the Witchcraft Act was formally repealed in 1736, 30 years after the Pittenweem witch trials.

Following the lynching of Janet Cornfoot, pamphlets in the form of anonymous letters start to circulate. The letters questioned Patrick Morton’s statements and even raised suspicions about the minister’s involvement and the treatment of the women.

Beatrix Layng, who had left the village, returned to Pittenweem in 1705 and became a whistle-blower about the false allegations. She spoke out about what happened and the torture the accused had endured, leading to the ‘confessions’.

Afraid of facing the same brutalities as Janet, Beatrix requested protection which the Privy Council granted. They ordered the magistrate to ensure her safety. However, the magistrate did not comply. They claimed Beatrix could be attacked at night, without their knowledge.

The Privy Council later launched an investigation into the murder and raised accusations against the magistrate’s lack of control over the events. Several suspects were identified and ordered by the Privy Council to be brought to the tolbooth in Edinburgh. They were later released. Further investigations fizzled out and no one was ever charged with the barbaric murder of Janet Cornfoot.

Who were the women?

Sadly, we don’t know more about the lives of the accused women and Thomas Brown. We know that Beatrix Layng was the wife of a tailor who sometimes had been the treasurer in Pittenweem. The fact that Layng was able to appeal to the Privy Council for protection suggests that she was not entirely without means.

Janet Horseburgh was the wife of Thomas White who had been a local baillie before he died. She successfully brought an action against her wrongful imprisonment and received a public apology from William Bell, one of the baillies, in 1710.

In his apology Bell conceded wrongdoing and acting on ‘idle stories’.

Header image: © Courtesy of HES (William Easton Collection).

From the mysterious Viking woman at Broch of Gurness to the marvellous Mary Burton – explore many more stories of Scottish Women’s History on our blog