You’ve likely already heard of some of the most famous UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as the Taj Mahal or the Pyramids of Giza. But did you know that there are now seven Scottish World Heritage Sites?

Sites are put on the World Heritage List if they are deemed so important that they belong to all of humanity. And managing a World Heritage Site is no easy task! It takes scores of professionals and volunteers to keep these important places running and protect them for the enjoyment of current and future generations.

Explore Scotland’s World Heritage Sites through archaeological artefacts, objects, and photographs, all chosen by the people who work at these fascinating sites.

Heart of Neolithic Orkney

The Heart of Neolithic Orkney is the northernmost Scottish World Heritage Site. It comprises four incredible domestic and ritualistic monuments that were built around 5,000 years ago. Together, they form the most important prehistoric landscape in western Europe.

Mysterious Carved Stone Balls

“Carved stone balls truly are a Scottish enigma. There are many theories as to what people used them for, but the truth is we don’t know. It may even be that they had no practical use and were purely symbolic or ceremonial.

“Designs and decoration vary, including grooved lines and spirals or protruding knobs or bosses, and sometimes even both. Regardless of their purpose, each one is made with considerable skill and patience. And they represent hundreds of hours of careful chipping, shaping, smoothing and decoration.” – Phil Hopkins (Monument Manager)

Midwinter light in Maeshowe Chambered Cairn

Maeshowe Chambered Cairn looks like a simple grassy mound to the unsuspecting eye. But what lies hidden beneath the dirt is an incredibly large and sophisticated tomb made from giant sandstone slabs.

“The last golden rays of the midwinter setting sun shining into Maeshowe on the shortest day of the year. An opportunity to celebrate the turning point in the solar year, and a welcome sign that the darkest days of the winter are behind us and better times are on their way.” – Phil Hopkins (Monument Manager)

Decorated Skaill Knife

© National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

“Skaill Knives get their name from the Bay of Skaill, of which Skara Brae sits on the southern shore. These objects are simple hand-held knives made by striking a smaller stone off a larger beach pebble. This creates a very sharp edge.

“Their main use would have likely been related to animal butchery. Although Skaill Knives have been found in abundance at Skara Brae, only small number have decorations such as this one.” – Catriona Martin-Lennie (Guided Tour and Visitor Experience Manager)

Old and New Towns of Edinburgh

Within the heart of Edinburgh, there exist two totally distinct but equally quintessential townscapes. Edinburgh’s Old Town, with its narrow closes and wynds, grew organically from the city’s 12th-century-origins.

The tight ‘fishbone’ street pattern is lined with many medieval tenements. They were some of the world’s tallest at the time. In the New Town, on the other hand, the streetscapes are wide open and invoke a sense of Georgian grandeur with grand terraces, gardens, and squares.

Corinthian Capital Model

© Edinburgh World Heritage Trust

“Our model of a Corinthian capital (the decorative top of a column) is a small piece of one of the World Heritage Site’s important architectural styles: Neoclassicism. Beginning in the 18th century, Neoclassicism was a cultural movement which drew inspiration from Ancient Greece and Rome. You can spot Neoclassicism all over the city. Look at the planned uniformity of the New Town, grand, columned buildings the likes of Surgeons’ Hall, and the monuments of Calton Hill. This is also why some call Edinburgh ‘the Athens of the North’.

“Our capital model features stylised scrolls and acanthus leaves. The plant is long associated with immortality and resurrection, and is typically used in Corinthian designs.” – Jen MacNeill (Communications and Interpretation Officer at Edinburgh World Heritage Trust)

Finials

© Edinburgh World Heritage Trust

“Railings are important features of the streetscape. This is especially true in the New Town, where elaborate Georgian ironmongery is expressed in finials – the ornamental toppings of railings. Different streets have distinctive finial patterns, each corresponding to areas of land ownership when the New Town was being built. Many say that Edinburgh’s abundance of railings is a consequence of the relative cheapness of cast iron at the time of the New Town’s construction.

“Ballantine Castings in Bo’ness holds the most comprehensive archive of Edinburgh’s finials. Pictured is their Southeast of Scotland section.” – Jen MacNeill (Communications and Interpretation Officer at Edinburgh World Heritage Trust)

The Crests of Acheson House

© Edinburgh World Heritage Trust

“Archibald Acheson acquired the land of Acheson House. The house was built in 1633 with his second wife Margaret Hamilton. Their crest (a cockerel, trumpet and Latin word vigilantibus, meaning ‘for the vigilant’) appears in stone above the front door and in the stairwell’s metal bannisters. You can also spot the amalgamation of their initials (A, M and H) in the stone crest.

“The property was passed through a series of wealthy merchants and incorporations. And in 1830, the property was purchased by John Slater.

By this time, a notorious brothel had settled in the building, called the “Cock and Trumpet”, referencing the Acheson family crest. By 1851, the building was subdivided into small renting flats. The burgh record of the same year records a mind-blowing 323 people living there” – Jen MacNeill (Communications and Interpretation Officer at Edinburgh World Heritage Trust)

The Flow Country

The Flow Country is Scotland’s most recent addition to the UNESCO World Heritage list. It is the only site in Scotland that has been inscribed purely for its natural significance (think of the Great Barrier Reef)! It’s a peatland, a type of wetland where plant matter doesn’t fully decompose, making them fantastic carbon stores. Learn more about the Flow Country.

Sphagnum Moss

Image selected by Brigid Primrose

Mosses are unique and strange plants. There are over 1,000 types of moss in the UK, but Sphagnum moss is the most integral to the Flow Country’s ecosystem. They don’t fully break down when the die. Instead, they form layers of peat which trap carbon – a win for climate change!

Sphagnum mosses can hold up to 20 times its volume in liquid and they are antiseptic! People have been using these mosses to dress wounds for hundreds of years. – Brigid Primrose (Biodiversity Adviser for NatureScot)

Pine Stump

Image selected by Brigid Primrose

Evidence, like the pine stump, tell us that this area used to be vastly different and covered in woodland.

As the climate got wetter 9,000 years ago, Sphagnum moss grew and spread. It caused the water-logged conditions that prevented trees from growing in this area.

The trees slowly died off and the peat burried and preserved them for us to find today. Stumps like these give us a glimpse into Scotland’s ancient landscape and how it has changed over thousands of years. – Brigid Primrose (Biodiversity Adviser for NatureScot)

Shining Pool Systems

© Sam Rose. Image selected by Brigid Primrose

Viewing the Flow Country from above allows you to fully appreciate the vastness of the site. You can also see the countless small pools of water all across the landscape.

When catching the light, the pools shine like jewels. They punctuate the landscape and prodice a home a variety of birds, plants, and insects. – Brigid Primrose (Biodiversity Adviser for NatureScot)

St Kilda

St Kilda is a collection of five remote islands 100 miles off the west coast of Scotland. They formed on the rim of an ancient volcano. The soaring sea cliffs are some of the highest in Europe, and this epic archipelago is home to almost one million seabirds – including a large colony of Puffins!

Humans braced the harsh conditions of these remote islands stretching back over two millennia. But the last 36 residents of St Kilda abandoned their homes in 1930, leaving behind their cultural traditions and way of life in favour of more liveable conditions.

St Kilda Mail Boat

“The St Kilda mail boats were a simple method to send messages, very much like a message in a bottle.

“A message would be put in a tin, placed in a hollow in a piece of wood and attached to a sheep’s bladder as a float. Set adrift from Village Bay, they would most often end up somewhere on the Western Isles. But they also drifted to Shetland and Orkney as well as Norway.

“The National Trust Scotland bought this mailboat in 2022 from a rural auction house in the US state of Michigan. Quite how it got there we’re not too sure.” – Susan Bain (Western Isles Manager for National Trust for Scotland)

Learn how you can make your own St Kilda mailboat

World War Two Wreckage

© Craig Stanford

“This flying boat patrol bomber was on a training exercise flight out of Oban on the 7th of June 1944 when it crashed into the steep slopes of northern glen on Hirta. It killed the 10 crew members on board. A recovery crew was sent to retrieve the bodies and break apart the larger fragments of wreckage to not alarm future pilots flying over St Kilda.

“I like this picture for showing how the Second World War reached even the furthest corners of Europe.” – Craig Stanford (Strategic Heritage Project Officer and previous St Kilda Archaeologist)

A Medieval Cross

© Craig Stanford

“The carved cross built into the window of the last house in the village, is a testament to the depth of time visible to the visitor on St Kilda. The style of the cross dates to the early medieval period, 800-1,000AD. It likely once marked part of the processual route around the main church on Hirta.

“It can be hard to see during the day, the best way to reveal the carefully carved ancient lines is in the raking light of a torch on a dark night.” – Craig Stanford (Strategic Heritage Project Officer and previous St Kilda Archaeologist)

The Antonine Wall

Built 2,000 years ago, the Antonine Wall marks the northernmost border of the Roman Empire. People came from the far corners of the Empire, making this a unique melting pot of cultures right here in ancient Scotland.

Samien Ware Shard

© Falkirk Council Museums – Samian ware chard with the potter’s mark and engraved with a woman’s name

“We expect the Antonine Wall to be all about the soldiers but there were civilians and women living next to the forts. This particular shard of pottery is special.

“Samian ware was produced in a small village in Gaul called Lezoux. It was so expensive that the potters would leave their mark on it. This means that we know the names of the potters whose merchandise ended up all the way on the Antonine Wall.

“On one of those shards, we found the name of a woman, Materna. She was probably the owner of the bowl and made sure everyone knew. We now have a link between a potter in Gaul called Cinnamus and a woman on the Antonine Wall. Not exactly what you would expect!” – Severine Peyrichou (Antonine Wall Project Development Officer)

Ditch at Watling Lodge

Picture of the ditch at Watling Lodge (© Rediscovering the Antonine Wall)

“The Antonine Wall is not very visible in the landscape. That’s not very surprising as it was made of turf 2,000 years ago! But the ditch survives in some areas and it very impressive. Imagine this stretching over 37 miles!

“Visiting Croy Hill, Watling Lodge or Seabegs on a misty day makes this even more mysterious. You can just hear the noise of the Roman camps in the wind…” – Severine Peyrichou (Antonine Wall Project Development Officer)

Metal Arm Purse

Forth Bridge

The Forth Bridge is an iconic landmark connecting Edinburgh to Fife over the River Forth. At the time of its construction, its structure and scale made it incredibly innovative and a marvel of Victorian engineering.

135 years later, it is still in operation and remains one of the longest cantilever bridges in the world!

Cantilever Chair Model

© Frank Hay, Queensferry Heritage Trust

“The structure of the Forth Bridge takes the form of three double-cantilever towers with cantilever arms to each side, linked together by two central spans.

“The cantilever principle was famously demonstrated by Japanese engineer, Kaichi Watanabe when he posed for a picture in which he acts as the supported central span, with two men acting as the cantilever towers supporting Watanabe with the counterweights made up of bricks.” – Karen Stewart (Forth Bridges World Heritage & Tourism Lead)

Vintage Paint Can

© Frank Hay, Queensferry Heritage Trust

“It is a common saying that a never-ending task is likened to painting the Forth Bridge. However, when the restoration was completed in December 2011, this was the first time the entire structure had been repainted in its history.

“The myth surrounding the continual repainting of the Forth Bridge has become another part of this iconic structure’s history. Originally referred to as ‘Indian Ink’, the now popularised name of ‘Forth Bridge Red’, emulates the original red oxide colouration the bridge had when it first opened in 1890.” – Karen Stewart (Forth Bridges World Heritage & Tourism Lead)

Large Rivet

© Frank Hay, Queensferry Heritage Trust – rivet removed during refurbishment of the Bridge showing some of the red paint

“The Forth Bridge was constructed between 1882 and 1890. It was the first major construction in Europe entirely of steel.

“In total, 54,000 tonnes of mild steel were used in the construction including an estimated 6.5m rivets.” – Karen Stewart (Forth Bridges World Heritage & Tourism Lead)

New Lanark

New Lanark World Heritage Site is a historic mill village that played an important role in industrialisation and social reform. Idealist Robert Owen transformed the village to be a progressive utopia with fair pay, education, healthcare, and excellent living conditions for mill workers.

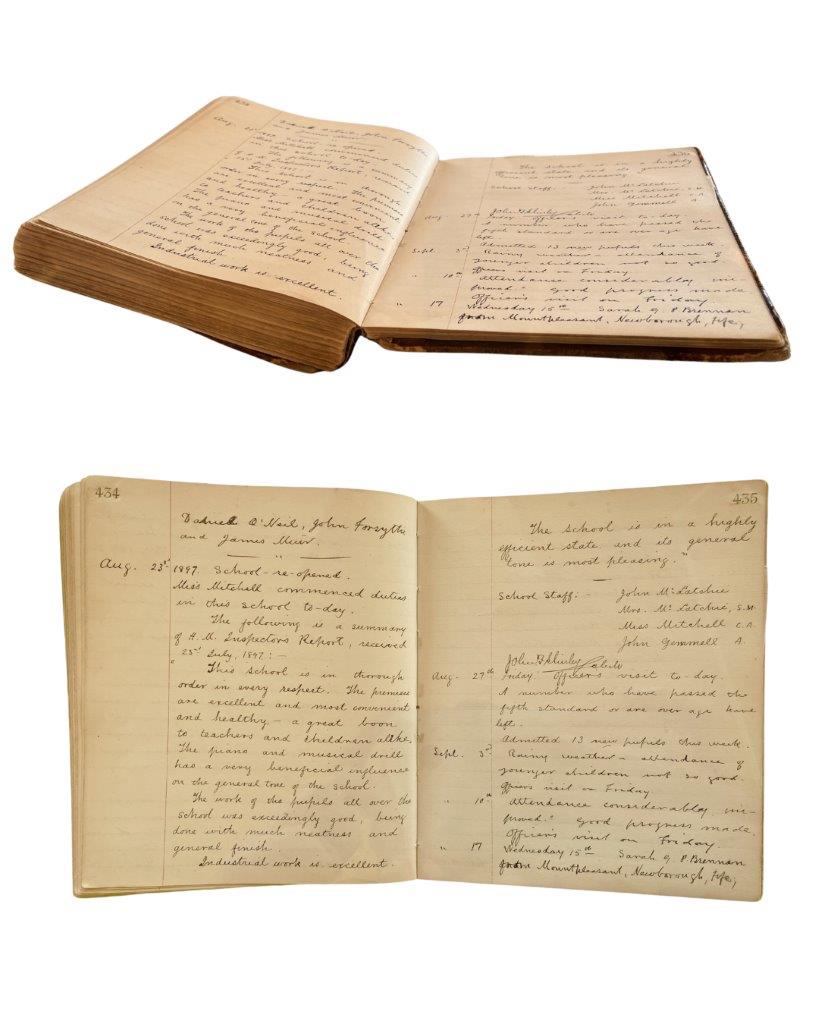

School Log Book

“Education is an integral part of New Lanark’s story. Robert Owen’s School for Children opened in 1816. It provided full-time education for the children who lived and worked in the mill up to the age of 10.

“Although Robert Owen had been dead for almost 40 years by the time this entry was recorded in New Lanark School’s log book in 1897, he would have been pleased that a visiting inspector found the school to be ‘in thorough order in every respect’.

“Despite the fact that many things have changed in the 128 years since these meticulous records, there is one thing we can all relate to – begrudgingly showing up for school in the ‘rainy weather’.” – Sophie Hunter (Learning and -Engagement Officer for New Lanark Trust) and volunteers

Waterwheel

“New Lanark’s historic waterwheel is an iconic symbol of the mill’s long history of hydro power. Installed in the early 1990s, the waterwheel bridges the past and present. It embodies the restoration efforts of the 1980s and 1990s which breathed new life into New Lanark. And it created the powerful and mesmerising structure we see today.

“The waterwheel, located on the site of Mill 4 which burned down in 1883, provides power to New Lanark Village, Mill 3, and New Lanark Hotel. The rhythmic sound of the wheel turning, the water droplets shining in the sun, and the renewable power it generates beneath our feet, are a fantastic backdrop to launch into the story of New Lanark. It is nothing short of a wonder to see in action.” – Sophie Hunter (Learning and -Engagement Officer for New Lanark Trust) and volunteers

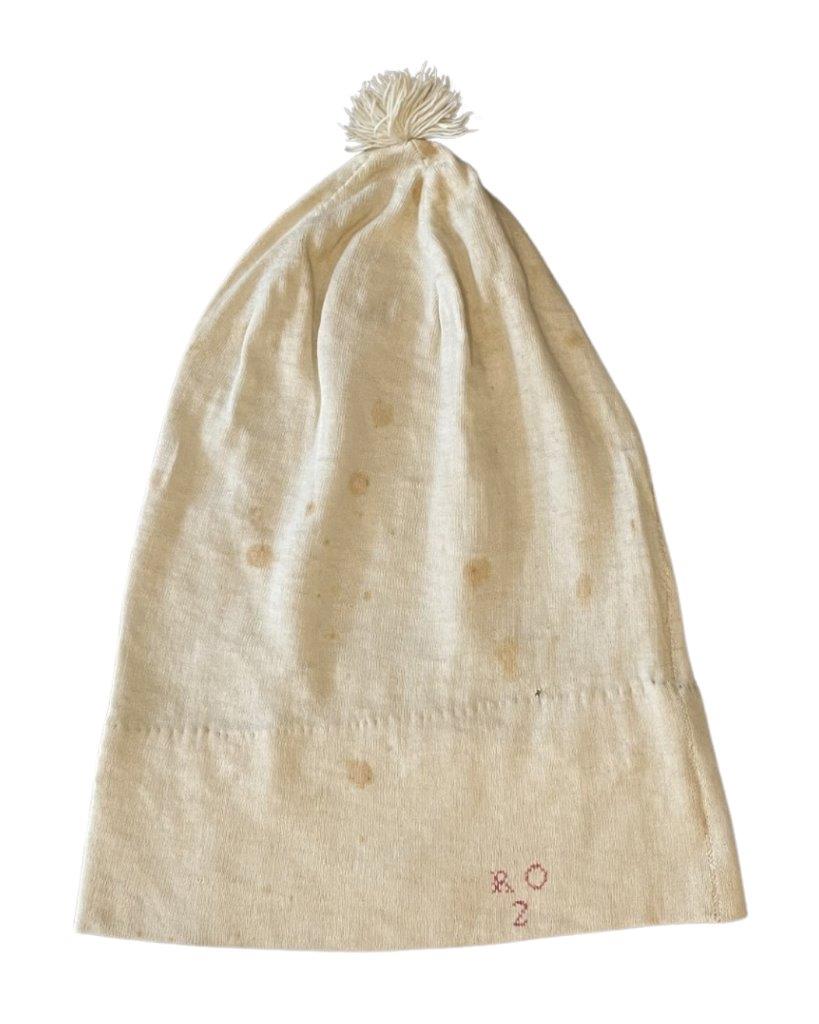

Robert Owen’s Night Cap

“This is Robert Owen’s nightcap. It is probably made of cotton. He likely wore it to protect him from the cold and his bed linen from hair oil, or pomade. Alongside his initials, R.O, is the number 2. 2 of 2, of 5, of 10? We aren’t sure how many nightcaps Robert Owen had but he clearly liked to keep track of the numbers.

“Before being donated to New Lanark, Robert Owen’s nightcap was in the possession of the Reverend John Pears. His great grandfather, Francis Pears, was a close personal friend of Owen’s. Francis Pears received the nightcap by another friend of Owen’s, and fellow socialist, James Rigby. We don’t know why Rigby had Owen’s cap or why he gave it to Pears but perhaps passing on articles of Owen’s clothing was how his friends remembered him.” – Sophie Hunter (Learning and -Engagement Officer for New Lanark Trust) and volunteers

Up for more Scottish World Heritage?

From myths and tales from Orkney to the multicultural stories of life at the Antonine Wall, you can uncover a lot more fascinating World Heritage history on our blog.